A major tradition of miniature painting in the history of South Asia and the wider Islamic world, Mughal manuscript painting emerged in the mid-sixteenth century in the royal ateliers (workshops) of the Mughal kings and remained highly influential until the late eighteenth century, well after the decline of its foremost patron, the Mughal court. Known for its naturalism, intricacy, luminosity and pluralism in both style and subject matter, Mughal miniature painting embodied a range of syncretic influences. Borrowing from styles as diverse as Persian miniatures, pre-existing manuscript paintings in South Asia and European Renaissance images, these paintings served as historical documents, visual aids for storytellers, illustrations for significant literary texts, ritual objects and accompanied scriptures and scientific literature.

Inspired by the aesthetic achievements of Shah Tahmasp’s court in Safavid Persia (present-day Iran), the Mughal emperor Humayun had successfully negotiated to take two Persian artists, Mir Sayyid Ali and Abd al-Samad, with him to India, along with military aid. In 1555, Ali and al-Samad set up the Mughal atelier after Humayun re-established the Mughal empire in India. As Mughal power and influence grew in the subcontinent, so did the painting style’s popularity and aspirational value for many smaller courts in South Asia.

As a result of this, contemporary scholars categorise Mughal manuscript paintings into two distinct categories — the imperial Mughal painting that was executed by the Mughal atelier and commissioned by the court, and a sub-imperial or popular form of Mughal painting, which was made by other, smaller ateliers without royal patronage. The difference is visible in the subject matter, intricacy and naturalism of the style, and the quality of materials used, while the similarities result from the standards set by the older and more lauded imperial atelier.

Also read: Del Tufo & Co – India’s earliest photo studio with branches from Madras to Colombo

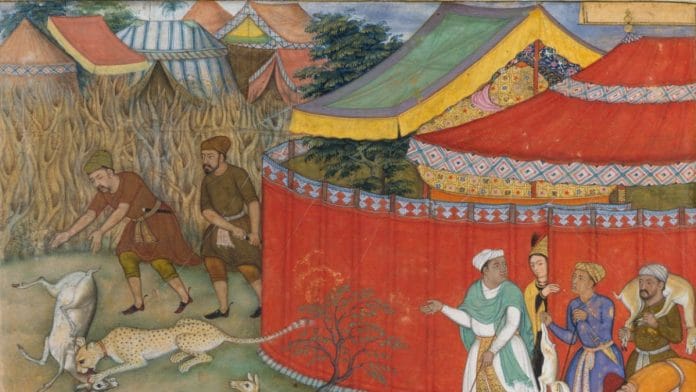

During Akbar’s reign — which came shortly after the Mughal atelier was set up — the size of the royal atelier grew from about thirty artists in 1557 to over a hundred in the 1590s and consisted of painters, colourists, calligraphers, bookbinders and other specialists. Mughal manuscript painting, sponsored as it was by the wealthy Mughal court, used fine quality paper which was imported from Persia and Italy. Pigments for colours were derived from similarly rare and expensive mineral sources such as lapis lazuli, orpiment, cinnabar and gold, amongst others. Illustrated manuscripts were often commissioned from texts of classical Persian literature, biographies of Mughal rulers and their ancestors, historical documents and Persian translations of works of ancient Indian literature. Illustrations of key scenes would appear alongside the calligraphic nastaliq text.

Additionally, in order to efficiently carry out a large number of projects — including illustrated manuscripts, individual paintings and designs for other objects — the hierarchy within the atelier remained somewhat fluid but highly collaborative. Within a given folio a master painter composed the image based on the text, which would then be coloured in by a junior artist. Further, there were some artists who specialised in portraiture or drawing animals. This achieved a level of consistency amongst different artists, but also maintained an individualistic style. For example, the artist Daswanth became well-known for his fantastical and frenzied compositions that stood in direct contrast to the work of Basawan, a contemporary, who became well-known for his talent for naturalism. Occasionally, the individual folios in the manuscripts also contained copious details such as the names of the artists involved, number of days taken to complete the artwork, the size of the atelier and so forth.

One of the earliest examples of illustrated manuscripts from this period is the *Tutinama (‘Tales of a Parrot’), which was written in the fourteenth century and illustrated in the 1560s. It displays indigenous flora and fauna within Persianate landscapes and includes the realistically proportioned dark-skinned figures associated with South Asia, rather than the willowy, fair-skinned youths emblematic of Persian paintings. Mughal artists were also introduced to European influences around this time when European emissaries and missionaries brought religious paraphernalia and examples of European art with them to the Indian subcontinent. This infused notions of pictorial depth and perspective into the sensibilities of the artists, though this always remained a minor component of the fully formed style of Mughal painting. Thus, the Mughal style of painting is characterised by the amalgamation of Persian, Indian and European styles.

Apart from the Tutinama, some other important manuscripts that represent the Mughal manuscript painting tradition include — the Hamzanama (‘Book of Hamza’), a fictional biography of the prophet Mohammed’s uncle Hamza ibn Abdul-Muttalib (c. 569–625), made during Akbar’s reign and considered to be one the largest and most ambitious manuscripts illustrated by the atelier with its 1400 paintings; the Akbarnama (‘Book of Akbar’), real-time documentation of Akbar’s reign, illustrated by at least forty-nine artists in the atelier; Shah Jahan’s biography, the Padshahnama (‘Book of the Ruler of the World’), known for its use of multiple perspectives and exuberant colours; and the Khamsa of Nizami, a collection of five poems from Nizami Ganjavi (c. fourteenth century), again produced in Akbar’s court.

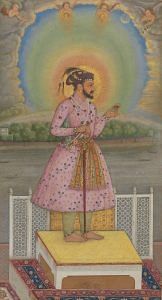

Over time, the structure of the atelier and the types of manuscripts being produced changed. In the 1580s and 1590s, the atelier mainly worked on dynastic histories such as the Timurnama (‘Book of Timur’, written in the sixteenth century) or the Baburnama (‘Book of Babur’, written in the fifteenth century), and translations of Hindu epics such as the Mahabharata (known as the Razmnama). These would often be large projects, both in the dimensions of the codices as well as the number of illustrations commissioned. In comparison, Persian poetical texts were much smaller in size and were worked on by fewer artists. During the reign of Jahangir, the focus moved away from manuscripts to muraqqas — albums of miniature paintings and calligraphic manuscripts — and the number of artists retained by the imperial atelier for long-term projects was significantly reduced because of the emperor’s tastes and interest in the works of only a few individual artists. Stylistically, Jahangir preferred naturalism and favoured elements of Persian painting along with a particular emphasis on portraiture.

Flourishing under the patronage of Akbar and Jahangir, the ateliers remained functional during the reigns of Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb. While Shah Jahan maintained funding for the atelier, his interest was mainly directed towards architecture. The paintings of this period were formal and lacked the flair for experimentation or aesthetic interest under the previous emperors, as the Mughal court viewed painting at the time as a medium of courtly representation. However, the muraqqas and illustrations in texts like the Padshahnama were highly naturalistic and technically accomplished. Aurangzeb’s religious orthodoxy led him to direct funding away from the atelier a few years into his reign, but for most of the 1660s the emperor tolerated painting as a courtly art. Several highly valued examples of portraits and durbar scenes in the Mughal style were produced in this period.

With the exception of a revival under the reign of Muhammad Shah (1719–48), patronage for miniature painting had dwindled enough in the eighteenth century that artists were forced to seek employment outside the imperial court, thus lending a strong Mughal element to the painting traditions of smaller kingdoms, particularly Rajput and Maratha courts. With the advent of British rule, the tradition of Mughal miniature painting, with its emphasis on naturalism, was incorporated into the Company school. Today, dispersed folios and, more rarely, whole manuscripts in the Mughal style, are housed at various museums across the world.

This article is taken from the MAP Academy‘s Encyclopedia of Art with permission.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit, open-access educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of art histories from South Asia. Through its freely available digital offerings—Encyclopedia of Art, Online Courses, and Stories—it encourages knowledge-building and engagement with the visual arts of the region.