A small vessel used to carry water for drinking and ritual ablutions, the kamandalu has been used since antiquity by Hindu, Jain and Buddhist ascetics and brahmacharins in South Asia. It is typically shaped like a globular or ovoid pot and carried either by its narrow neck or a handle across its top. With its early forms made from clay, dried gourds or coconut shells, it is also made from wood and metals such as brass and copper.

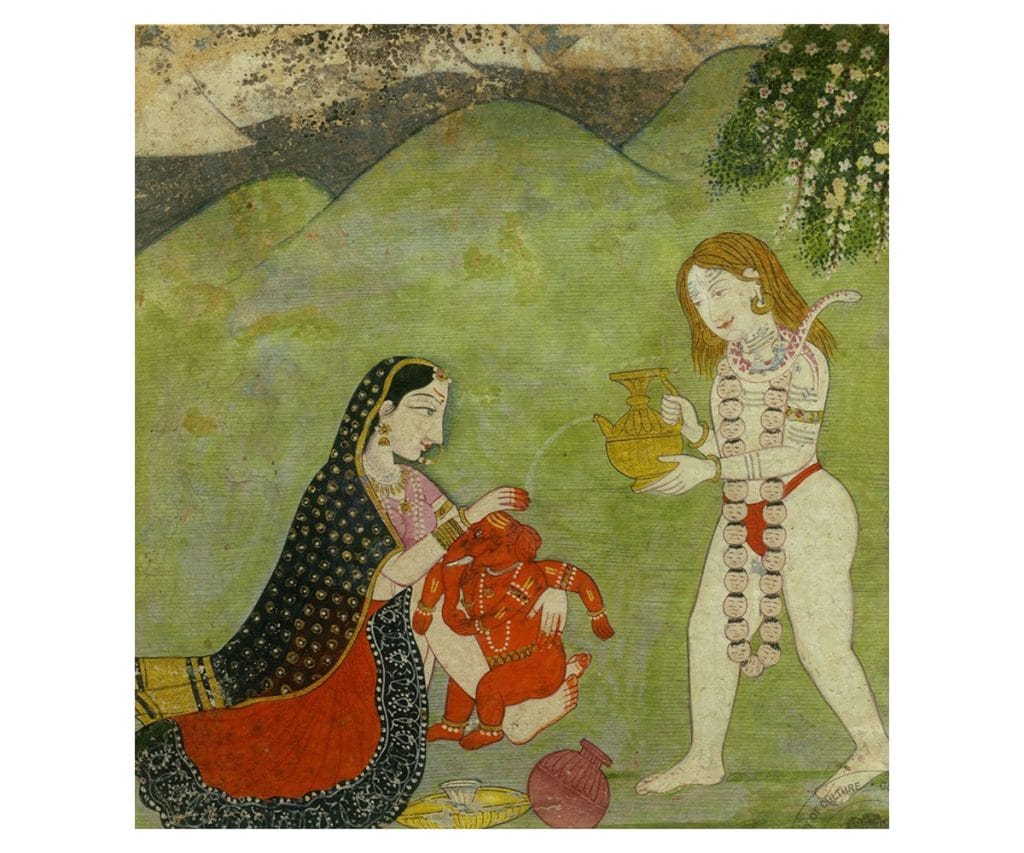

The oldest extant specimens of the kamandalu, dated between the fourth century BCE and second century CE, include earthenware vessels found at the sites of Taxila in present-day Pakistan, and Saheth-Maheth, Bhita and Sanchi in present-day India. In South Asian iconography, the kamandalu is attributed to a number of deities and mythological figures, particularly those who take an ascetic form, such as Brahma and Shiva. When associated with the kalasha, which it may resemble, it is linked with prosperity, wish-fulfilment and abundance, and attributed to water deities and gods of wealth.

Encompassing different handheld vessels used for water in the monastic context, the kamandalu shows a variety of forms. Often called a kundi or kundika, particularly in Buddhist literature, some of the earliest known examples of the kamandalu feature an ovoid belly that tapers into a high narrow neck and ends in a small mouth with a protruding rim. A thin, reed-like opening allows for the outflow of water; many such vessels feature an additional funnel-like spout at the shoulder through which water was filled into the kamandalu.

Featuring a round or flat base, they were held directly at the neck, which was sometimes high enough to accommodate the full hand and at other times one or two finger-widths high. Generally undecorated, the vessels sometimes featured simple ornamentation around the lip of the mouth or spout. Other forms of the kamandalu, particularly contemporary designs, resemble the globular kalasha or kumbha, with a wider mouth across which they feature a handle. These kamandalus sometimes feature a lid and a spout for pouring, akin to a teapot.

The kamandalu is mentioned in Vedic literature, and also features in the works of the fourth century BCE Sanskrit lexicographer Panini. In Hindu mythology it is among the primary implements associated with Brahma, the Vedic god of creation. Often believed to hold the primordial waters from which all life emerges, it is held in one of his four arms while the others commonly hold an akshamala or rosary, and a book.

Agni, another Vedic deity, is also depicted holding a kamandalu and akshamala, modelled after the figure of Brahma according to some texts. Shiva and the related Buddhist deity Avalokiteshvara, commonly depicted as ascetics, are also often shown holding the kamandalu. It also appears in Buddhist literature such as the Jataka stories and in the Sanskrit play Mricchakatika by Shudraka (early centuries CE), mentioned as the water vessel used by both Buddhist and Hindu monks and religious students.

Pakistan; c. 200 CE; Gray schist; 66.3 cm; The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio

In one of the first iconic visual depictions of Brahma, he appears as a simply clad figure carrying only a kamandalu; appearing in low relief on the early-first-century Bimaran reliquary from Gandhara, this figure is rendered in repoussé gold, flanking that of the Buddha. According to scholars, these early representations of Brahma shaped depictions of Maitreya in the Gandharan Buddhist iconography of the second and third centuries CE. This is seen in his topknot or jatamukuta and his flask, which is depicted as a kamandalu or kundika containing the amrita that signifies the possibility of salvation to his followers.

In addition to its chief associations with austerity and spiritual discipline, the kamandalu is sometimes conflated, in its spoutless form, with the kalasha, which is symbolic of plenty and fertility, or the amrita kalasha containing the nectar of immortality. In these forms it appears as part of the iconography of Hindu river deities such as Saraswati and Ganga, and deities who preside over wealth, such as Kubera. Minor goddesses such as the wish-fulfilling Harasiddhi and Surabhi are also, accordingly, depicted with a kamandalu. A spoutless kamandalu appears as an iconographic emblem in first-century Kushan imagery from Mathura, as the vessel of nagas and yakshas, known for their use of intoxicating beverages.

The kamandalu continues to be used by renunciants and ascetics today. Hindu ascetics are usually seen with a kamandalu and a staff, alms bowl and rosary. According to Jain monastic authorities, the kamandalu, used for ablutions, is among the few possessions monks are allowed, alongside the rajoharana, a broom to dust away insects before sitting.

This article is taken from the MAP Academy‘s Encyclopedia of Art with permission.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit, open-access educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of art histories from South Asia. Through its freely available digital offerings—Encyclopedia of Art, Online Courses, and Stories—it encourages knowledge-building and engagement with the visual arts of the region.