Lashed by the dirt thrown up by the horses of the men hunting him down, Maulana Rahmatullah Kairanawi bent even lower: The East India Company’s soldiers never realised that the cowering grass-cutter was the theologian on whose head a price of Rs 1,000 had been placed. “The country belongs to God, and command belongs to Maulvi Rahmatullah,” cried the mujahideen he had led into jihad against the English in 1857. Fanaticism proved no match for modern artillery, and the Enfield Pattern 1853 rifled musket, though. Leaving behind his land and wealth, the cleric fled to Mecca.

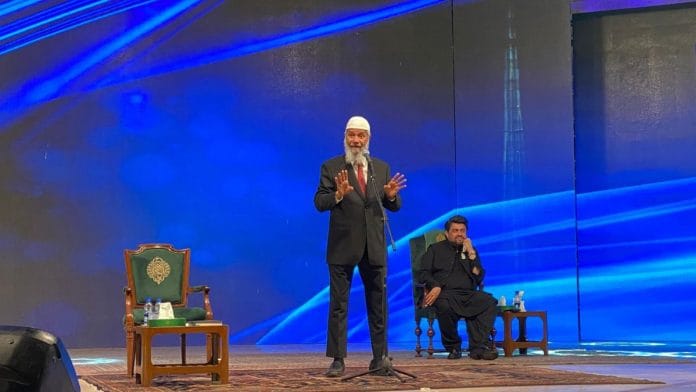

For days now, Islamic pop fanatic Zakir Naik—wanted in India for inciting religious hatred—has been generating outrage in Pakistan. Like his critics in India and Bangladesh, liberals in Pakistan have been discovering that misogyny and chauvinism lie at the heart of Naik’s message. To many, it seems bizarre that a country being torn about by religious bigotry invited Naik as a state guest.

Like others on the religious Right wing, Naik has drunk deep from the poisoned wells of Indian identity movements of the nineteenth century—movements which locked the region’s religions in violent contestation against each other. For post-colonial generations traumatised by the economic and cultural power of the West, this new kind of Islam asserted that faith needs no reform or introspection.

Tied to the two-century-old intellectual legacy of Kairanawi, the Islam Naik propagates emerged as traditional religious authority slowly disintegrated under colonialism. Islam—just like Hinduism—increasingly feared annihilation by scientific materialism and Evangelical Christianity.

Kairanawi’s Izhar-ul-Haqq, a rebuttal of missionary critiques of Islam, profoundly influenced Ahmad Deedat, a South African cleric financed by Saudi Arabia’s religious establishment. The pop-Salafism pioneered by Deedat would, in turn, prepare the ground for Naik and his televangelist media empire.

Also read: Zakir Naik is missing India—‘Hindus love me, Pakistan International Airlines doesn’t’

The great debate

Eminent officials of the East India Company, editors of Agra newspapers, leading notables of the city, and hundreds of ordinary spectators fought for space inside the missionary school compound nestled inside Agra’s bazaar. For two days over the Easter Week of 1854, leading intellectuals were to go to war, pitting the God of the Emperor, Muhammad Shah Zafar, against the God of the East India Company. “The natives, both Mahommedan and Hindu, were trooping in groups that could not all gain access to the building,” the missionary TG Clark recorded.

From the time of the ‘Abbasid caliphs’, historian Hans Harmakaputra reminds us, that the courts of Islamic rulers had often hosted similar munazara, or debates. This was different, though: The question of who the one true God was had begun to become a public matter.

Ever since the terrible drought of 1837, historian Avril Powell has written in her brilliant account of the encounter between colonial missionaries and Islam, efforts to spread Christianity had intensified. An orphanage had been set up in Agra, which missionaries hoped would form the core of a future Christian community. Tensions had begun to rise, too, around the new Anglo-Oriental college in Delhi, where Europe’s science had begun to seduce a generation of young élite Muslims and Hindus.

From the mid-nineteenth century, a succession of books appeared, subjecting Islam to sometimes hostile scrutiny. Aloys Sprenger, the Austrian-born physician and linguist who led the college until 1851, caused some offence with his biography of the Prophet Muhammad, which suggested he shared the “amiable foibles and selfish virtues” of other men of his age.

Then, in 1852, the college’s eminent mathematics professor, Panipat-born Ramchandra—long a religious sceptic—converted to Christianity, together with the surgeon Chaman Lal. Abdullah Athim, an Amballa resident serving as a magistrate in Sindh, followed them, publishing an extended refutation of Islam.

Kairanawi, the son of an eminent cleric, emerged as the leading voice of clerical opposition to these tendencies. Tracing his intellectual heritage to Sayyid Ahmad Shahid of Rae Bareilly—the leader of a failed jihad against Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s empire—Kairanawi’s work aimed at securing a civilisational triumph of Islam, scholar Seema Alavi has noted. The Farsi-language Azalat al-Shukuk, published in 1853, directly addressed missionary critiques of Islam. Later, Kairanawi would publish elaborate refutations of Christian doctrine, like the Trinity.

Equipped with access to the latest European works of Biblical criticism, Powell writes that Kairanawi and his lieutenants seem to have demolished his ill-equipped missionary opponent, Karl Pfander. The events of 1857, though, demonstrated that the sword was mightier than the pen. Even though he secured the patronage of the Ottoman court in Turkey, Kairanawi never succeeded in returning home.

Also read: Zakir Naiks shouldn’t be the only ones interpreting Islam. Make way for feminist views

Islamic televangelism

The man who carried forward Kairanawi’s message was not a theologian nor a scholar of Islam. Likely born around 1918, in a village near Surat, Ahmed Deedat left India at the age of nine, moving with his father to Durban in South Africa. There, scholar David Westerlund records, he studied at a madrasa, and then the Hindu-run Tamil Institute. Lacking the means to continue his education, though, Deedat began working at a store. There, in 1939, he first encountered Christian missionaries, who relentlessly challenged his religious beliefs.

Finding a copy of Kairanawi’s Izhar-ul-Haq in the store’s warehouse, so the story goes, Deedat discovered the intellectual tool he needed to respond. “When the British conquered India they realised that anytime anybody will give them troubles [sic.], it will be the Muslims because power, rules, dominion were in their hands,” he later told a journalist. “And the Muslims were militant people in contrast with the Hindus who were at that time as docile as the cows they were worshipping.”

Though Deedat does not mention the race of the missionaries, scholar Samia Sadouni believes they were almost certainly Black students of the Adams Institute, which had become the powerhouse of the community after Apartheid closed other educational doors. To Deedat, she writes, “Christianity rather than racial politics was the aggressor and main threat to the Muslim world.”

Following a brief immigration to Pakistan in 1949, Deedat returned home, disillusioned by the new Islamic Republic. In 1957, he founded the Islamic Propagation Centre in Durban, centred on Dawah, or proselytisation. The centre received extensive assistance from religious institutions in Saudi Arabia, a country which would grant him state honours in 1985.

Even though Apartheid was the defining experience of Deedat’s South Africa, Sadouni notes, he made no mention of it in his work. The Apartheid regime, for its part, was content to tolerate Deedat’s anti-Evangelist polemics. In the 1980s and 1990s, Deedat engaged in a succession of debates with prominent Evangelical opponents—the American neo-fundamentalist Jimmy Swaggart, the Palestinian Christian Anis Shorrosh and the Swedish Pentecostal pastor Stanley Sjoberg.

Ahead of a trip to the United Kingdom, Deedat’s publicity material proclaimed: “‘An invasion in reverse. The British ruled over India, Egypt, Malaysia, etc. for over a hundred years. Now for the conquest of Britain for Islam!”

These English-language public debates, modelled on American Evangelist television, were circulated worldwide by video cassettes and books. The West, he preached, was a moral morass beset by alcoholism, homosexuality, prostitution and sexual depravity. The only answer was Islam: Israel’s Jews, America’s Christians, India’s Hindus all had to be converted, and drawn into the fold.

Also read: Pashtun girl asks Zakir Naik about rising paedophilia in Islamic societies. He says apologise

The new messenger

Little is known about just how Naik came into contact with Deedat, but together with his father, Abdul Karim Naik, the young medical student invited the South African cleric to a conference held in Mumbai in 1987. Deedat returned again the following year. Then, in 1991, Naik left his fledgling medical practice and set up the Islamic Research Foundation. According to Sadouni, Deedat was scheduled to return again in 1995, but was denied an Indian visa after his derogatory comments about Hinduism provoked angry protests in Durban.

These controversies didn’t stop Naik’s rise, though. Like his mentor, Naik studiously avoided political controversy: There is no mention in the IRF’s archives of the Babri Masjid dispute, or even the anti-Muslim violence which tore apart Mumbai in 1992-1993. This allowed Naik to remain close to the state’s political class, while at once sharpening group boundaries between Islam and Hindus.

Focussed on a new generation of educated, middle-class Muslims, Naik’s English-medium, suit-clad Islam served as an opiate which dulled the pain of discrimination, economic backwardness and political disempowerment. The pseudoscientific gloss was thin—but Naik delivered his bizarre fabrications on issues like evolution and Charles Darwin with admirable self-confidence.

The rise of the Indian Mujahideen delivered the first challenges to Naik’s cosy arrangement with power. Even though there is no accusation Naik was ever involved in terrorism, key figures in Mumbai’s jihadist landscape—among them, Lashkar-e-Taiba student Islamists Rahil Sheikh and Feroze Deshmukh—worked as volunteers in the IRF. Later, Islamists involved in terrorism in Bangladesh, as well as Islamic State recruits, were found to be fans of Naik’s speeches.

Institutions like the IRF, terrorism researcher Abdul Basit noted, “may not be directly involved in violent radicalisation of vulnerable individuals, but the worldview they construct through their teachings make the job of violent-extremist organisations easier.”

The real significance of Naik’s journey to Pakistan ought to be to engender reflection on the consequences and future costs of the toxic religious identity politics that was unleashed under colonialism. Failure to find other languages of belonging will mean remaining locked in a cycle of hate.

Praveen Swami is contributing editor at ThePrint. He tweets with @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Ahmed, Lots of people are famous. Bin Laden, Nasarallah all famous. Naik is a failed doctor. Spreads lies and poison in the name of religion. He has managed to convince some like you that he is right. Violence will likely stem from his supporters. They need to be investigated and monitored. The ‘millions’ who will rape and murder seeking justification in a book or what people like Zakir spew are the real threat to the world safety. They are fewer than they think. But screaming online does make one seem powerful. Go to Pakistan. Join the fight against non islamic forces there. Why just spout hate online?

IF YOU THINK ANYINE IS FAN OF NAIK IS TERROIST THAN. YOU ARE FOOLING YOURSELF MILLIONS AND MILLION UNDERSTAND WHAT HE IS ABOUT AND HE NEVER TEACHES FIGHT OR JIHAD, ONLY PROBLEM IS HE IS GOOD AND FAMOUS, WHICH HURTS MANY MANY IDIOTS.

Kanhaiyya Hum Sharminda Hai Tere Qatil on unhe uksanewale aur unhe bachanewale kewal zinda nahi panap rahe hain. Hindus should not be allowed express themselves. After all isnt it enough we call Zakir Naik bad may be with some justification. So everyone suppress theur religion because bad actors and bad ideologies cannot be directly called out.

The latest NCPR report recommends Madarsas be closed. A deradicalization program must be executed before transfering the children to regular schools. Talking about these things is not enough, action is needed. Zakir Naik is not where the problem stems from. It stems from having a religion which says if you dont follow me and worship what I ask you to worship, you will go to hell and my followers will physically harm you in this life. Praveen and other journalists always make it sound that all religions are bad. This toxicity results from exclusive religions. Not all of them require conversions, proselytize and force destruction of native identities. Stop this mindless equating in the name of false fairness. Leftist agenda pushing is not as important as addressing the real issue.

The real significance of Naik’s journey to Pakistan ought to be to engender reflection on the consequences and future costs of the toxic religious identity politics that was unleashed under colonialism.

So they did it because Christians did it first. And their toxicity means no one else can protect their identity. Proseletyzing is cultural invasion. It has destroyed many indigineous cultures.

Left wing tendency to equate all things in false fairness is why these journalists try to justify Naik.

Zakir Naik thrives because the media eco system protects him. First proselytization should be criminalized with 8 years solitary confinement. Second insidious apologists should be exposed and deplatformed.

Same regious identity politics is happening today also. RSS and IRF are run on same ideology that their religion is under threat and people need to unite under the religious banner to defeat the agressors who are spreading moral depravity in society.