Over the past 15 years, India’s central government and numerous state governments have put in place health insurance programmes that entitle low-income households to free healthcare at public and empanelled private hospitals. Health equity and universal health coverage are explicit goals of these programmes. In new research (Dupas and Jain 2021), we study gender equity in the Bhamashah Swasthya Bima Yojana (BSBY)1 health insurance programme, which was launched in the state of Rajasthan in 2015, and is similar in design to the national Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY)2.

Our starting point is a dataset of insurance claims filed for all 4.2 million hospital visits between 2015 and 2019.3, including patient age, gender, residence address, hospital visited, dates of admission and discharge, and service(s) received. We geo-coded hospital locations and patient addresses, which allowed us to calculate proximity to hospitals and the distance travelled for every hospital visit. Finally, we linked the insurance data to the 2011 Census and data on three rounds of village-level (gram panchayat4) elections5. To our knowledge, the dataset we compiled from these various sources is the first dataset of its type in India and allows us to study care-seeking under insurance with unusual granularity.

Large gender disparities in hospital visits under insurance

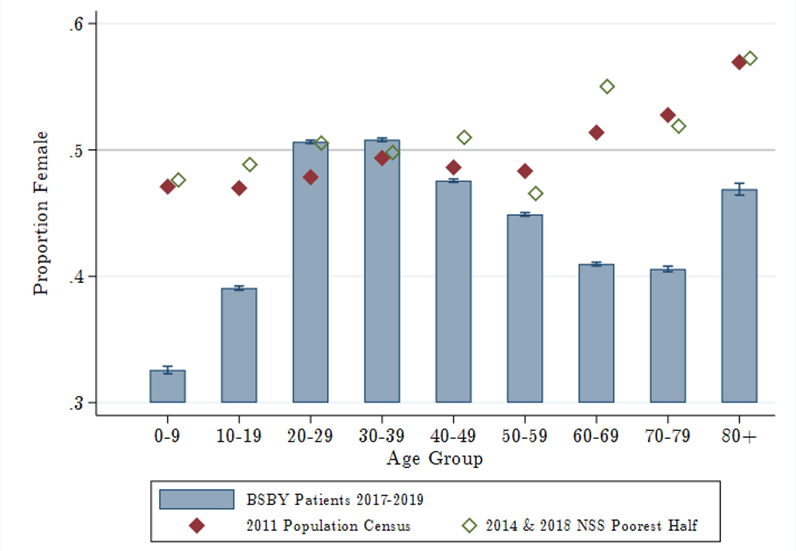

Females account for only 45% of all hospital visits, with the biggest gaps among children under 15 years (33%) and adults 50 years and older (43%) (Figure 1). These gaps are far larger than can be explained by Rajasthan’s skewed population sex ratio. We also show that differences in underlying health needs cannot account for these gaps: across several health conditions, the female share of hospital visits under BSBY is over 10 percentage points lower than would be expected based on gender-specific illness prevalence estimates from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study for India. Based on this comparison, we estimate that there are over 225,000 missing female hospital visits between 2017 and 2019 for nephrology, cardiology, and oncology care alone.

Figure 1. Age-specific female share of hospital visits under insurance

Note: (i) The blue bars represent the share of insurance claims within each group that are for females. (ii) The red diamonds are the female share of the population, and the green diamonds are the female share of the poorer half of the population, which approximates the BSBY-eligible population.

These results are consistent with gender disparities documented in other insurance programmes in India (Shaikh et al. 2018). As a result of these gaps, public spending is effectively pro-male. Even inclusive of obstetric care, programme spending on females in 2019 amounted to 44.4% of total spending. In contrast, in the US, around 57% of yearly Medicaid spending is on females.

Biased household resource allocation contributes to gender disparities

While there may be several factors that create female-specific barriers to healthcare utilisation (for example, lack of safe transport), we provide evidence that gender-biased resource allocation within the household plays a significant role. To demonstrate this, we build on the intuition that, in the presence of gender bias, any costs of care-seeking will amplify gender disparities. First, we use surveys conducted with patients to document widespread out-of-pocket (OOP) charges by hospitals, for care that should be free under the programme.6 Females are significantly less likely to utilise hospitals or services with higher OOP charges, suggesting that these charges deter care-seeking for females. Female utilisation also decreases sharply with distance to the closest hospital, another measure of care cost. Finally, even households that do seek care for females, are seen to travel significantly further for male than for female care. Jointly, these results provide strong evidence that households value and allocate more resources to the health of males than females.

Also read: Downside of dowry crackdown — women’s decision-making power falls, domestic violence goes up

Reducing the cost of care-seeking does not reduce gender disparities

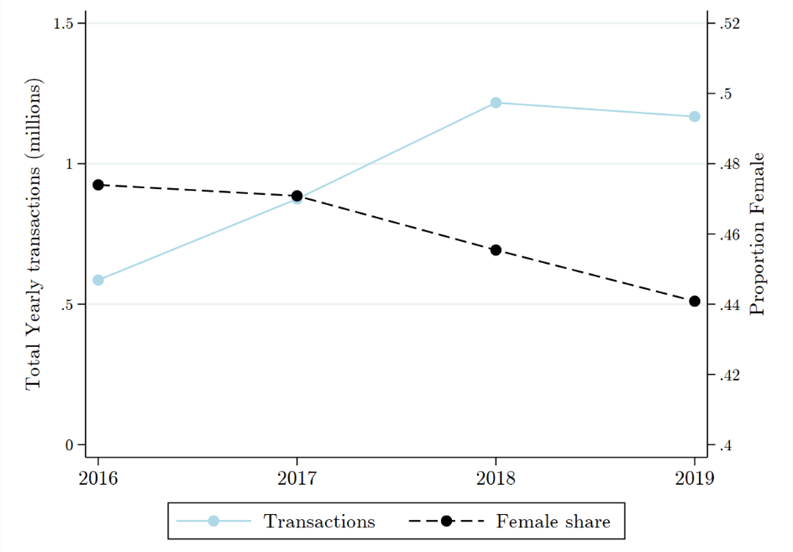

We use the empanelment of new hospitals near villages – which reduces the distance to the nearest private BSBY hospital – to examine what happens to gender disparities when the cost of care-seeking is reduced. Both female and male hospital visits increase immediately and significantly, but the female share of visits remains unchanged. This may seem counterintuitive, but in the presence of gender bias, reducing the costs of care may increase female utilisation but fail to reduce gender disparities because households prefer to spend their marginal rupee on males over females. This helps explain why the female share of visits decreases over four years of implementation, even as the programme expands and total utilisation increases substantially (Figure 2). Although the programme expanded rapidly, going from roughly half a million hospital visits in 2016 to 1.2 million visits in 2019 (excluding childbirths), the female share of visits decreased over this period. Expanding access alone is insufficient to close gender gaps.

Figure 2. Programme expansion and gender disparities

Note: (i) The blue solid line is the total hospital visits each year between 2016 and 2019, excluding childbirths. (ii) The black dashed line is the female share of all hospital visits over the same period (corresponding to the right-hand vertical axis).

Also read: No title, no money — Women grow 80% of India’s food, but new farm laws unlikely to help them

Exposure to female leaders helps reduce gender gaps in utilisation

Prior literature has shown that, in the Indian context, exposure to female leaders in government can reduce bias in perceptions of, and aspirations for, women and increase investments in female health (Beaman et al. 2009, Beaman et al. 2012, Bhalotra and Clots-Figueras 2014). We exploit randomised reservations for women in gram panchayats across three five-year terms between 2005 and 2015, to test whether local female political representation helps mitigate disparities in utilisation of health insurance in Rajasthan.7 The female share of hospital visits in a panchayat increases by 0.8 to 1 percentage point with each reserved electoral term, among children and women of childbearing age. The evidence suggests that these effects are driven by long-term increases in maternal and child health investments, and female agency in villages with repeated exposure to female leaders – rather than through increased awareness of BSBY. However, the benefits of reservations do not extend to elderly women.

Concluding remarks

Our finding that a large universal health coverage policy has not reduced gender disparities over four years of implementation goes against the general assumption that expanding geographical access and reducing the costs of healthcare will automatically reduce inequalities. Such gender-neutral policies may increase female levels of utilisation but closing gender gaps requires strategies that explicitly target barriers to female care-seeking and gender bias.

Notes:

- BSBY is a cashless health insurance scheme of the state government of Rajasthan. Under this scheme, those covered under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) and Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) are eligible for treatment benefits of up to Rs. 30,000 for general illnesses and Rs. 3 lakh for critical diseases.

- PMJAY is one of the two components of the Ayushman Bharat Yojana (National Health Protection Mission), which was launched in 2018. PMJAY is a health insurance programme that aims to reduce the financial burden on poor and vulnerable groups, arising out of catastrophic hospitalisation episodes.

- The dataset was obtained from the state government of Rajasthan, under a MoU (Memorandum of Understanding) between the government and J-PAL (Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab) South Asia.

- A gram panchayat is the cornerstone of a local self-government organisation in India of the Panchayati Raj system at the village or small-town level and has a sarpanch as its elected head.

- These data were obtained from the State Election Commission of Rajasthan.

- We sampled random subsets of hospital visits on a rolling basis between October 2017 and August 2018, and conducted phone surveys (N = 20,969) with patients using contact numbers included in the claims data. The sample covered private hospital visits across 13 different services, as well as public hospital visits for childbirths and haemodialysis.

- The 73rd Amendment of the Constitution required that one-third of all council members and Sarpanch seats be reserved for women in each five-year term, with reserved seats selected randomly with replacement from the list of Gram Panchayats before each election.

Pascaline Dupas is a Professor of Economics at Stanford University. Radhika Jain is Asia Health Policy Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Stanford University. Views are personal.

This article was first published by Ideas for India (I4I).