For some years now, I have been hosting a Lord Macaulay party at my home for fellow Dalit activists, writers, and intellectuals. Noted scholar D Shyam Babu even gave him the moniker Mahatma Macaulay. Now, this would obviously rile up many Indians who support the decolonisation project India has embarked upon in recent years. PM Narendra Modi said this week that he wants to uproot Lord Macaulay’s influence from Indian education and reverse the colonial mindset.

To the British colonialists, the Battle of Plassey may have been a cakewalk, but ruling the colony called India was not. The caste phenomenon turned out to be their biggest headache in ruling this newfound territory. If you study the disruptive force that Macaulay unleashed upon Indian society, you will understand why Dalits want to call him a Mahatma.

Before coming to India, Mahatma Macaulay had some idea of caste. In his 10 July 1833 speech in the House of Commons, he was worried: “The worst of all systems was surely that of having a mild code for the Brahmins who sprang from the head of the Creator, while there was a severe code for the Sudras, who sprang from his feet. India has suffered enough already from the distinction of castes.”

However unintended it may have been, the colonialists saw caste-based prejudices and discrimination as inappropriate to the civilised world. The campaign that Mahatma Macaulay unleashed on caste was sustained by future British administrators. The colonialist empathy for the Dalit cause that was on display during the Round Table Conferences in the early 1930s was the outcome of what he had sown. BR Ambedkar’s inclusion in the Viceroy’s Council as a labour minister mirrored that civilising project of the colonial masters that Lord Mahatma Macaulay had begun.

Lord Macaulay’s efforts of seeding sciences and European morals for India bore fruit with Charles Wood’s despatch in 1854. Macaulay’s English education was finally implemented in India, but the monster of caste kept nagging the rulers.

“The low castes are still far behind the main body of Hindus in the matter of education…there was formerly a deep-seated prejudice against the admission of low caste children in public schools,” notes Progress of Education in India.

The British rulers encountered yet another mutiny-like situation by the caste-ridden Indian society in the form of a violent resistance to the entry of Dalit children into the newly evolving English education system. Still ruled by the East India Company, the education department issued a circular on 20 May 1857 stating that no boy should be refused admission to a government college or school merely on the ground of caste. The Hunter Commission noted that the insistence on the inclusion of low caste children was repeated by the Secretary of State in 1860.

After Wood’s Despatch, a battle unfolded between caste and colonialists. In the Kairana district of the Bombay Presidency, six Dalit villages were burned down. Elsewhere, Dalits’ crops were attacked, and children chased away. Fearing social pollution, many schools were shut as privileged caste children withdrew from schools.

The Hunter Commission, set up in 1882, asked the British administration this: “Establishment of special schools or classes for children of low castes be liberally encouraged.” In his report, WW Hunter expressed his government’s inability to enforce the inclusion of depressed class children.

That’s when the idea of separate schools came. The Commission had already identified the existence of 16 separate schools in the Bombay Presidency and four in the Central Provinces. Much against the wishes of the upper caste nationalists, the British colonialists established separate schools for Dalits all over India. A school was set up in my native village in Azamgarh in Uttar Pradesh, too. I am a product of the same school, although this Harjan Bal Vidyalaya admitted students from all castes.

Today, the English education that the British introduced in India is unfairly treated as just a language project. It wasn’t. Mahatma Macaulay’s Minutes on Education (1835) is a living testimony of all that he advocated—focus on sciences and Western philosophy. India is the greatest beneficiary of that colonial project. Think of Indians’ superiority in IT and excellence in sciences without Mahatma Macaulay’s Minutes on Education. Think of India’s legal ecosystem without IPC, CrPC, district courts, collectorates, educational institutions, railways, and communication connectivity.

Macaulay imagined a free India

After my JNU days, I have often wondered why Indians hate Mahatma Macaulay more than they hate Lord Clive. After all, Lord Clive sported wartime headgear, held a sword in one hand, gun in the other. There was guile in his eyes. He stared at Indians, fired at them; won an empire for England in the Battle of Plassey in the year 1757.

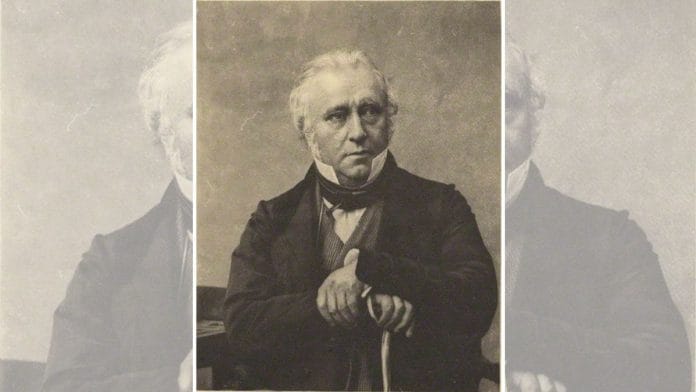

Lord Macaulay, on the other hand, came to India with two fountain pens and an ink pot. He dressed like royals, sported a gentleman’s hat, and walked with grace.

Did Mahatma Macaulay have contempt for India?

Look at what he said in his Government of India speech in the House of Commons on 10 July 1833:

It would be, on the most selfish view of the case, far better for us that the people of India were well governed and independent of us, than ill governed and subject to us; that they were ruled by their own kings, but wearing our broadcloth, and working with our cutlery, than that they were performing their salams to English collectors and English magistrates, but were too ignorant to value, or too poor to buy, English manufactures. To trade with civilised men is infinitely more profitable than to govern savages.

“I allude to that wise, that benevolent, that noble clause which enacts that no native of our Indian empire shall, by reason of his colour, his descent, or his religion, be incapable of holding office,” he said elsewhere in the speech.

Did the Lord demean India with his Minutes on Education, when he said: “A single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.” Or was he just making a point to highlight the role of reason-based Western education for India? He was neither mocking India nor his own country, the father of Indian modernity was just making a rhetorical point and saying take what is best of the time.

Macaulay imagined India as a free country—free of England. That’s the reason I designate Mahatma Macaulay as the ‘earliest Gandhi’.

Also read: Death sentence for Hasina, acquittal in Nithari—how TV news covered two verdicts

Why Indians hate Macaulay

The so-called ‘colonial mindset’ is emancipatory. It is not just the gulf between two languages, Sanskrit and English. It is the widest hole between two ways about society. In pranam, a Dalit’s head must bend. In Good Morning, their head is held high. Dalits’ dhoti must not spread beyond the knees, but the full pants have no such hierarchies.

Robert Clive defeated India but didn’t question caste. Mahatma Macaulay envisioned India as a free nation and critiqued caste. That holds the clue to why the hatred for one surpasses the other.

So vilified is Mahatma Macaulay that even Britons have developed Indians’ dislike of him.

When I hosted Mahatma Macaulay’s birthday party in October (also celebrated by us as the birth event of English, the Dalit Goddess in Delhi), the noted British weekly The Economist called my efforts ‘Quixotic’ in its editorial titled Macaulay’s Children – Quarrelling over India’s Past, dated 28 October 2004.

Chandra Bhan Prasad is a columnist who wrote the book, ‘Caste by 2050’. He is associated with the Mercatus Centre, George Mason University, US.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

Dalits should also fall in love with Mahatma Adam Smith and say goodbye to the Congress party.