The excavation at Harappa that commenced on 5 January 1921 gave impetus to a new found curiosity among a fresh batch of young archaeologists of India. Years that followed this feat yielded new evidence that opened doors to the unknown. By 1924, it was formally declared to the world that the excavations at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro have pushed back the antiquity of the subcontinent to 3rd millennium BCE by bringing to light a buried civilisation with distinct and unknown cultural traits.

Eventually the notion of civilisation, which was hitherto unknown became the highlight of this work. This, as a result, left many of us to chase civilisation. There is an ongoing trend where the Harappa Civilisation has become central to historical discourse and people are tracing their roots back to this first wave of urbanisation. This civilisation has left an immense mark on the culture-scape, and we owe a lot to the advancements made at that time. But the fact is that it’s the culture that creates a civilisation.

The two terms—civilisation and culture—are often used as each other’s synonyms. And there isn’t much discussion about how these phrases should be used in an archaeological context. In fact, I too have struggled with it. In this week’s column, we will look at the meaning and significance of both in a country like ours with diverse archaeological heritage.

Also read: What came after Harappan Civilisation? This small Haryana village has answers

Archaeological culture

What comes to your mind the moment you hear the term ‘culture’? Is it the morals and the values you learn, or the traditions and rituals you follow or simply the sum total of everything that gives you an identity? According to Edward Burnett Tylor, an anthropologist who is credited with defining culture in 1871, culture is “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, customs and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.” In a nutshell, culture as per Tylor is the sum total of everything humans have learned in order to exist, everything they produced in order to survive and everything they passed on as an inheritance.

Culture is complex and there is no single definition that could do justice. When I was first introduced to the term, I was asked to look at ecology as it governs the way we live, what we eat, what we wear among many things. Revolving around ecology is our subsistence pattern and then comes our traditions and rituals, thus defining culture as an adaptive behaviour. What is interesting is that each of these aspects of culture have an intangible side, which is transferred as knowledge, and the tangible side forms a major component of archaeological culture.

The usage of the term ‘culture’ entered archaeology in 19th century. It was used to describe the different groups that were distinguished on the basis of archaeological records of a particular site or region. In other words, the material culture—artefacts and remains from a specific timeframe and within a specific geographical area that is classified and grouped together. Once classified, an equation between artefacts and human culture is made by making the assumption that artefacts are the expressions of cultural ideas or norms.

From the beginning of archaeological investigation in the subcontinent, most archaeological cultures are named after specific types of pottery. For example, Painted Grey Ware (PGW) Culture is named after a fine grey pottery with painted motifs that defines technological advancement in ceramic making. In Northern Black Polish Ware (NBPW) Culture, which is a grey/black pottery with glazed slip, glazing was a new feature in the ceramic assemblage of the region. There is also an Ochre Coloured Pottery (OCP) Culture, which as the name suggests is classified on the basis of a type of ochre coloured pottery. Stone Age cultures are also classified on the basis of stone technology and their gradual evolution/development like Palaeolithic Culture translated to Old Stone Age. Similarly, the Neolithic Culture translated to the New Stone Age along with the advent of agriculture and the Megalithic Culture is named after Megaliths.

Initially it was thought that these artefacts that stood out in the assemblages, especially in the case of ceramic culture, are linear and succeed one another. For instance, OCP is succeeded by PGW, which in turn is succeeded by NBPW as found at sites like Hastinapur and Ahichchhatra in Uttar Pradesh. But today, fresh investigations and new dates have proved that many of these ceramic cultures (not just the ones mentioned here) are not always placed in linear fashion but are merged with one another. For example, we now know that PGW and NBPW co-existed.

Such new data and our evolved understanding of the past question if difference in identity is not always expressed through ceramics as identity is multi-dimensional. How far can we take ceramics as an ultimate marker of identity and follow the law of classifying artefacts?

As someone who has been working on ceramics and digging trenches for over 10 years, I am now compelled to question whether it is wise to characterise societies entirely on a single ceramic type without carefully considering material and non-material characteristics of their culture. Archaeological views have developed over time and it is now widely understood that similar materials do not always correlate to a single society. And dissimilar material goods do not always indicate a separate society.

Also read: Did Harappans exploit animals for dairy? Lipid residue from Gujarat’s Kotada Bhadli has answers

Culture is not civilisation

Civilisation, unlike culture, is defined by certain parameters. The term is derived from the Latin word ‘civitas’ or city directly linking it to urban settlements. It is a complex society made up of different cities with cultural and technological advancement. The society is divided into specific jobs, so not everyone has to focus on growing their own food. There is specialisation and class structure, trade matrix, art and sophisticated architecture/monuments.

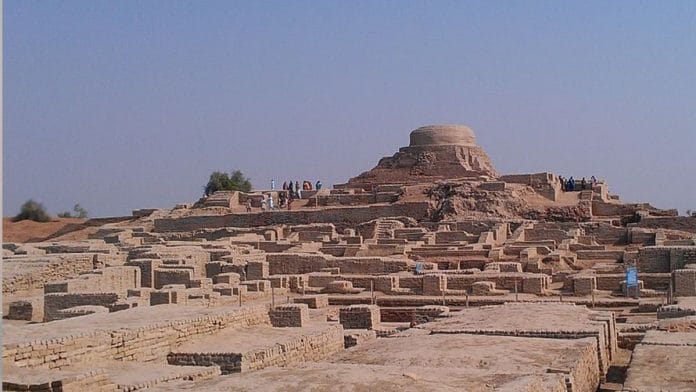

As per this definition, the earliest civilisation of the subcontinent is the Harappa Civilisation. The presence of urban cities like Harappa, Mohenjo-Daro, Dholavira, Rakhigarhi, stratified settlements, presence of complex trade matrix, manifestation of art and sophisticated architecture and most importantly the presence of script has helped the civilisation in gaining the title.

Not every settlement within the realm of the civilisation is urban in nature. There are rural, semi-rural, industrial and agro-pastoralist settlements as well. This diversity is unified by cultural traits that makes Harappa a unique example of a civilisation. Here too, cultures make up civilisation not the other way around.

Taking the case of other archaeological cultures, most of the research is either based on sites or a particular geographical area, which lacks evidence of many parameters that would make them a civilisation. The PGW Culture is spread over a vast area from Bahawalpur in Pakistan to Vaishali in Bihar but our knowledge about its social complexities, trade activities, regional diversity among many other things remains limited. All we know are some aspects of an archaeological culture based on the classification method.

Having worked at many PGW sites and it’s cultural material especially the ceramics, I know that we have a long way to go before we call it a civilisation. However, some scholars have gone ahead and clubbed many such ceramic cultures and termed it Ganga Civilisation as these cultures are in Ganga plain. This perhaps could be an interesting way of looking at the cultural diversities, which for long were segregated on the basis of ceramics. But only time (and a lot more digging) will tell.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)