Pakistan’s infiltration into J&K on 5 August 1965 required only ‘tacit understanding’, but a full-scale army operation required Presidential assent. The Pakistan Army chief, General Musa Khan, insisted upon written orders. But in a peculiar twist of events, it was the Foreign Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto who took charge, flew to the picturesque Swat valley in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where President Ayub Khan was camping, and received the directive which bore the title ‘Political Aim for the Struggle in Kashmir’. Bhutto could not have wished for anything more: This proclamation put him above all his cabinet colleagues, and the army had to rely upon him to interpret the terms of the directive.

Information Secretary Altaf Gauhar quotes from the directive: “(The army was) to take such action that will defreeze the Kashmir problem, weaken India’s resolve, and bring her to the negotiation table, without provoking a general war”.

With characteristic bluster and arrogance, which appears to be that of Bhutto’s, it went on to say, “As a general rule, Hindu morale would not stand more than a couple of hard blows at the right time and place. Such opportunities should therefore be sought and exploited”.

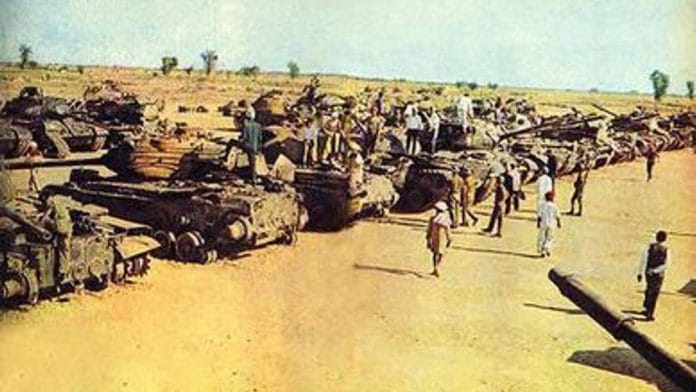

Thus, in the early hours of 1 September 1965, Pakistan launched its full-fledged attack on India. It drove a column of seventy tanks and two brigades to capture the strategically critical town of Akhnoor, thereby disrupting the supply link between Punjab and Kashmir. If Akhnoor fell, the Kashmir valley would become very vulnerable.

Pakistan did meet with initial success, and Chamb was captured on the first day itself. The 12th Division, under Major General Akhtar Hussain Malik, was proceeding towards Akhnoor, which was only twelve miles away. At this critical juncture, Malik was removed from the command, ostensibly for the failure of Gibraltar (but more to prevent him from claiming victory in Akhnoor, which at that time appeared imminent). Much to the consternation of his army chief, General Musa Khan, Malik was replaced by Yahya Khan. Both Ayub and Yahya were Sunni Pathans, while Musa Khan was a Shia and Malik was an Ahmadiyya.

Also read: The war Pakistan lost and India didn’t win

From air strikes to boundary crossings

Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri took little time to convene the cabinet meeting, which endorsed his decision to authorise the Indian Air Force (IAF) to halt the Pakistani advance to Akhnoor. At 5:19 pm (IST) on 1 September, the IAF launched 26 ground support missions, destroying a dozen Pakistani tanks, several heavy guns and sixty-two vehicles. This left Pakistan scurrying to the Security Council, which had in fact received a report on 31 August from the United Nations Military Observer Group for India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) stating that “the present military conflict might reach wider dimensions quickly, leading to outright military confrontation beyond Kashmir”.

The next day (2 September), Shastri convened a series of meetings with his cabinet colleagues, leaders of Opposition parties, the top brass of the defence forces and the officials of the home, defence and external affairs ministries, where the border situation was discussed threadbare. Shastri explained to his colleagues that in order to defend Kashmir, it was essential to make a diversionary attack on West Pakistan, which would “force them to give up their Kashmir venture in order to defend their own territories”.

After a free and frank discussion on the pros and cons of escalation—including a war on three fronts—West and East Pakistan as well as China, India defined its threefold war objectives on 3 September.

These were; a) to defeat the Pakistani attempts to seize Kashmir by force, and to make it abundantly clear that Pakistan would never be allowed to wrest Kashmir from India, b) to destroy the ‘offensive power’ of Pakistan’s armed forces, and c) to occupy only the minimum Pakistani territory necessary to achieve these purposes, which would be vacated after the satisfactory conclusion of war.

Immediately after declaring these war objectives, Shastri proceeded to the AIR to address the nation: “(our) quarrel is not with the people of Pakistan. We wish them well; we want them to prosper, we want to live in peace and friendship with them. What is at stake in the present conflict is a point of principle. Has any country the right to send its armed personnel to another with the avowed objective of overthrowing a democratically elected government?” And he went on to add, “there are no Hindus, no Muslims, no Sikhs, no Christians, but only Indians. I am confident that the people of this country, who have given proof of their patriotism in the past, will stand united as one man to defend the country”.

Thus, for Pakistan, the date of commencement of the 1965 war was 3 September, when India formally notified its intention of “occupying Pakistan territory across the International border in Punjab and Rajasthan sectors” to fulfil its objectives of ousting Pakistan from Kashmir.

Pakistan was harbouring the impression that it could limit the military operations to Kashmir, for it felt that India would never have the temerity to cross the undisputed international border. This was indeed a difficult decision for India as well. RD Pradhan, in his book Debacle to Resurgence, has recorded YB Chavan’s statement, “The decision to launch an attack on Pakistan across the IB was a desperate move, and carried high risks. The step will change the complexion of the entire situation. If we fail, and I cannot imagine it, the nation fails. The nation won”.

Meanwhile, on 2 September, the UN Secretary General, U Thant, wrote an identical letter to Shastri and Ayub asking the two countries to “cease fire” immediately. Shastri’s response on 4 September was sharp: “Your message is such as this might leave the impression that we are responsible equally with Pakistan for the dangerous developments that have taken place. Unless your message is read in the context of the realities of the situations as they have developed, it tends to introduce a certain equation between India and Pakistan which the facts of the situation do not bear out”.

When the UNSC, under the chairmanship of Ambassador Goldberg of US, passed a similar resolution on 11 September, India’s permanent representative to the UN, G Parthasarathy made it clear that, “while a ceasefire was desirable, it would not come unless Pakistan was identified as the aggressor, and asked to withdraw”, a reiteration of the position that the war was started by Pakistan on 5 August.

This indeed was the key point of contention in the Tashkent summit, which was convened in January of 1966.

Sanjeev Chopra is a former IAS officer and Festival Director of Valley of Words. Until recently, he was director, Lal Bahadur Shastri National Academy of Administration. He tweets @ChopraSanjeev. Views are personal.

This is the second article in a series on the Tashkent Declaration.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)