The bizarre spectacle, which began with a contested accusation of plagiarism targeting celebrated historian and public-facing intellectual, Vikram Sampath, played out on social media and courtrooms in India last week. The saga devolved into farce when one of the accusers began brandishing a list of would-be supporters that turned out to be filled with fake names.

The sad episode that transfixed academic communities in India and the United States left me reflecting on the events of the fortnight past — a time that could have gone much differently and inflicted much less damage for its entire cast of characters.

As a practising academic surgeon with an appointment at a prominent medical school in the US, my charge is to deliver world-class medical care and expand the horizon of my field through research and teaching. My colleagues and I publish in peer-reviewed journals, edit book projects and make frequent academic oral presentations.

Occasionally, we are asked to give oral presentations at a conference, and organisers may ask that we submit a transcript of a speech to be published in a compendium to a conference — often called the “proceedings” of the meeting. Since these ‘proceedings’ are not always peer-reviewed — meaning rigorously reviewed with robust critique — the submissions tend to be more informal than other submissions.

So what would I do if I read one of those proceedings attributed to a colleague that seemed rather familiar? What if I placed that colleague’s work into a plagiarism detection software and found that my colleague had, indeed, closely paraphrased my work, even reproducing lines? What if the colleague had put appropriate citations in some places in the text and complete references, but had a few lapses in locating some citations following each paraphrased passage?

What if that colleague had published five well-received books of hundreds of thousands of words and many other peer-reviewed publications, but the overlooked citation issue was found in just one non-peer-reviewed journal? What if this colleague is otherwise a rigorous, exemplary scholar with no record of similar lapses?

Academic ethics would compel me to contact the colleague, even one I may not know, and apprise this person of failure to cite or place quote marks around those passages and ask that corrections be rendered. If the colleague ignored my entreaty, contacting the journal and requesting corrections to the submission would be my next step. Failing that, only then might I escalate the matter and inform this person’s affiliated institutions to investigate.

But that is not how it went for Vikram Sampath.

Also Read: Savarkar wouldn’t have found a place in today’s politics: Historian Vikram Sampath

How Sampath was targeted

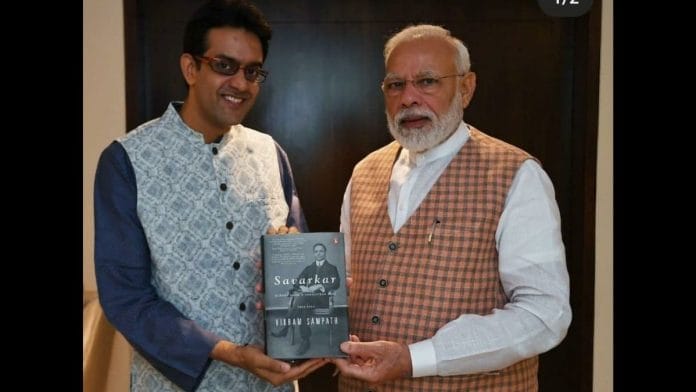

The template I illustrated above, was not the one followed by his accusers — the three academics at US-based institutions. Instead, by every appearance, Sampath was targeted for scrutiny because some fellow historians disapproved of the subject of Sampath’s best-selling biography, the story of Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. Savarkar, lesser-known among Indian nationalist leaders who opposed British colonial rule, was jailed and tortured in a remote penal colony even as he prolifically wrote in support of Independence. Savarkar, an atheist, propounded anti-colonial ideas along with a conception of “Hinduness” or Hindutva, which is now seen in the ideology claimed by India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.

Georgetown University’s Ananya Chakravarti, Rutgers University’s Audrey Truschke and Santa Clara University’s Rohit Chopra, a non-historian, teaching Communications, decided to subject the corpus of Sampath’s work to the Turnitin software that compares an author’s work to other previously published work. In order to do so, they would’ve had to copy and paste all of Sampath’s books into the software. It is to be noted that no other significant errors were detected, save a solitary paraphrased paragraph in one of the books.

The trio’s next course of action was to probably search online manuscripts written by Sampath and subject them to the software. As Sampath says, a single article — a transcript of a speech delivered at the India Foundation in 2017, later submitted for a non-peer-reviewed “proceedings” publication — was supposedly found to have errors in citation. The work of two American professors, Vinayak Chaturvedi and Janaki Bakhle was cited in the references, and at multiple points in the five-page essay, but a few passages paraphrased from Bakhale’s work were identified as lacking citations or quote marks, as convention dictates.

But did the academic triad contact Sampath and helpfully suggest amending, while the vast majority of his work was above reproach, a few errors were detected in a single passage in a likely long-forgotten speech transcript? No. Instead, the three authored a letter to the Royal Historical Society, an honorary society of historian scholars based in the United Kingdom that granted Sampath membership based on his scholarly accomplishments. The three co-authors remonstrated that Sampath’s error in that article was similar to that of their “callow undergraduate students” and a “predation” so severe that Sampath should be directly disbarred from the Society.

Also Read: Plagiarism, data manipulation hurting India’s research, govt panel raises alarm

A career-ending punishment

Being dismissed from membership in an honorary society, sort of like a Fellowship in the Royal College of Surgeons from my vantage, would be an unthinkable setback. So Truschke, Chopra and Chakravarti were calling for a sanction akin to demanding a career-ending punishment despite there being no evidence that Sampath’s work displays any pattern of similar lapses.

Indeed, none of what the accusing trio did transpired through discreet private communications, as academics usually correspond. The very first act of this saga was a public “release” of the letter on Twitter by a contributing writer to Al Jazeera.

Once in the social media realm, thousands responded to a flurry of posts impugning and defending Sampath. Facing an unsavoury trial by Twitter and an open attempt to destroy his career by a direct appeal to the Society, to which he had just been elected, Sampath approached Indian courts. Sampath successfully obtained an injunction enjoining Twitter in India from platforming the damaging accusations against him.

A few days later, Truschke tweeted out a list of ostensible supporters of her cohort’s adventurism against Sampath. The list, comprising mostly of the academics’ own colleagues at Georgetown and Rutgers, apparently included celebrity historians and columnists such as Ramachandra Guha and Pratap Bhanu Mehta and even senior political leaders. Within hours, that spectacle turned comical when many of these “signees” repudiated their association with the list and reported that their names were forged without permission.

But the real damage was done. Sampath’s name now had a prefix of “plagiarism-accused” and Truschke gloated that his Wikipedia had a ‘new entry on the charges’ written nearly in real-time.

Why did Chakraborti, Truschke and Chopra act against Sampath with such malice? Why did they seek the equivalent of the historian’s “death penalty”?

Also Read: Who is Savarkar? And should we discuss him? 14-state survey throws up stunning results

A history of ‘scholar-activism’

The academics are not novices to what they call “scholar-activism” and controversy. All three accusers have a long history of relentlessly denying the existence of Hinduphobia, and clashing with Hindu American groups they label ‘right-wing’ or ‘Hindutva’. Sampath was targeted for his apparent ‘sin’ of penning a widely-acclaimed narrative of Savarkar, who the three activists considered the very font of that Hindutva ideology.

Chakraborti and Chopra were among co-sponsors or speakers at an activist-oriented online meeting that sought to “Dismantle Global Hindutva” (DGH). That meeting caused international outrage as it featured multiple academics who insisted that Hindutva could not be “dismantled” without dismantling Hinduism, the religious tradition. Those attacks on Hindutva were seen by many Hindu Americans as a ploy to imply that they have “dual loyalty” and are, by default, supportive of India’s ruling party — the BJP.

Truschke is already facing a defamation lawsuit for conspiring to defame the Hindu American Foundation (HAF) by falsely alleging that the Foundation sends funds to India to support a “slow genocide” or “sponsor hate”. (Disclosure: I am a co-founder of HAF). And Chopra made news recently when Twitter summarily suspended his ‘India Explained’ Twitter account after he posted a controversial tweet about Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Truschke and Chakraborti even released a “field manual” that presumed to warn against “Hindutva Harassment,” but actually trafficked bizarre Hinduphobia, such as proscribing “elite Hindu-centric” ideas held by Hindu students on campus. Truschke’s recent release of a graphic accusing a campus Hindu students’ organisation, the Hindu Students Council, of promoting Hindutva, led to vociferous pushback from college students who insisted that the charge of “Hindutva” is a common gaslighting tactic to silence American Hindu voices.

It is certainly okay for academics to be invested in activism, and my work with HAF certainly points to my own commitment to advocacy. But when that activism is focused in one’s own area of scholarship — as we often see in South Asian studies — it is critical for those activists to remove ideological blinders, divulge their conflicts of interest, and avoid a parochial overreaction to a scholar who may not toe an ideological line.

Impugning the probity of a colleague is a serious charge. When a colleague has no record of malfeasance, added restraint is required. Playing out personal or ideological grievances through vicious tweets or public letters to historical societies, weaponising a plagiarism charge, is the antithesis of restraint.

The brutal academic targeting of Sampath simply need not have happened as it did.

When academia is politicised and dissension ostracised, the biggest loser is academic integrity.

Aseem Shukla, M.D. is a Professor of Surgery (in Urology) at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and a co-founder of the Hindu American Foundation. Views are personal. He can be reached at @aseemrshukla