Some 40 years ago, I lived in Caracas, Venezuela, for two years. Our daughter was born there, which technically makes her a caraqueña and a venezolana. At that time, Venezuela was widely seen as a rambunctious but stable democracy. Power alternated between two parties, the right of centre COPEI and the left of centre Acción Democrática or AD.

It was a country driven into financial trouble primarily by the mismanagement of its exchange rate. They hung on for too long to a grossly overvalued bolívar. We used to call it the curse of 1973. In that year, oil prices went up, and, as the curse of Atreus in Greek mythology, abundance brought ruin to this oil-producing nation.

The Venezuelan elites decided that fiscal and monetary rectitude was unnecessary. They haughtily opted for an overvalued local currency. They exported oil. So, they decided to import everything else. In the 1960s, Venezuela was an exporter of staples like rice. The land was very productive and many crops could be grown. But year after year, Venezuelan producers were systematically disincentivised to produce anything as imports were cheaper.

Fall of the Bolivar

The state-owned oil company PDVSA was not particularly inefficient. But it was a source of “rents” for the political and bureaucratic leadership. The elites lived well. They were referred to as “Rico Venezolanos” or rich Venezuelans. They all had properties in Florida and Spain. I remember a conversation I had with one of my rich acquaintances. I said, “Señor: Usted rico” (Señor: You are rich). He said, “Señor Rao: Yo no rico. Yo no tengo barquo; yo no tengo avionetta” (Mr. Rao: I am not rich. I don’t have a yacht or a private plane). This exchange pretty much sums up the mood of the elite in the country.

In the meantime, there was very little productive economic activity. Who would build factories when one could import things cheaply? A growing underclass, especially in urban centres, took to petty crime and disorganised delinquency. There was a suppressed sense of unease building up.

Finally, as former Chair of the Federal Reserve of the US, Paul A. Volcker, raised US interest rates mercilessly in the 1980s—the economy cracked. The bolívar went through a massive devaluation. This could have incentivised domestic production. But the “long and distributed lags” of economics came into play. And in the meantime, the economy went for a toss. I remember one comic event. President Herrera Campins went on TV and said that although the national currency had devalued 300 per cent during his term, people should not forget that one venezolana had been crowned Miss World and one had been crowned Miss Universe during his term.

In the 1990s, destiny finally caught up with the “Ricos”. A controversial ex-army officer called Hugo Chávez grew popular and became President. He was neither a conservative like Herrera Campins, nor a swashbuckling social democrat like Carlos Andrés Pérez. Chávez was clearly a leftist. He was also a prickly nationalist. He hated the IMF, which was seen as a malicious tyrant hurting the Venezuelan poor. Chávez lucked out a bit. Oil prices started climbing. He had money and he spent it on lush subsidies for his constituency—Venezuela’s poor. Again, there was no attempt made to incentivise productive economic sectors.

Chávez got really cocky. He thought he could antagonise the US. He forgot, or he did not know about leftist leaders of Guatemala and Chile who had tried to take this dangerous path. Chávez nationalised American investments in an aggressive and miserly manner. And he committed the sin of aligning with the ultimate ‘bête noire’ of the US—Cuba. Over time, Venezuela became the most sanctioned country after Iran. The “Ricos” left, taking their wealth and entrepreneurial energies with them. Venezuela descended into dysfunctional socialism. And when oil prices softened, the heavily sanctioned country was hit really hard.

Luckily for Chávez, who had acquired a saintly reputation, he died in 2013 before the worst hit Venezuela. That fate was reserved for his unlucky successor, Nicolás Maduro. A former bus driver and trade unionist, Maduro continued with leftist, anti-US rhetoric, which he thought his base wanted to hear. The trouble is that stern people in Washington DC also heard it.

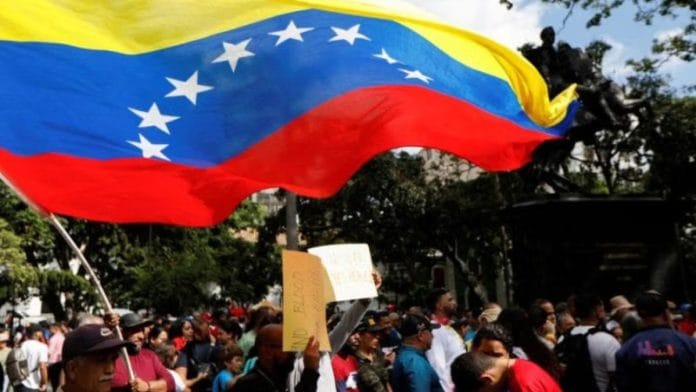

The grip of sanctions tightened, and a Greek tragedy of inevitable confrontation was set in motion. Unlike Chávez, Maduro was clumsy. He could have graciously “lost” an election and retired to Spain. He hung on, and the usual suspects, the New York Times, the BBC, and their hangers-on targeted him as “illegitimate” and “undemocratic”, expressions that they use whenever their demonisation campaign gets going. The result is what we have seen in the last few days.

Also read: US military intervention in Venezuela — the 3 lessons to remember

The racial-ethnic divide

So, in all this mess, what is the elephant in the room that no one wants to address? The supporters of Chávez and Maduro have largely come from the Venezuelan urban underclass, positioning themselves against the ricos. So, this whole thing can be analysed through the familiar Marxism lens of class conflict.

This class-based view, however, is limited. The Venezuelan ricos were and are not just wealthy. They are white Caucasians. They are descendants of Castilian aristocrats and, later, German and Italian migrants. By contrast, the majority of Venezuelans trace their ancestry back to Indigenous peoples, along with a smaller African component. They are most certainly not of white European origin.

Chávez was clearly of Indigenous descent. Maduro’s mother was from Colombia and was, in all probability, of mixed ancestry with a strong Indigenous component. Ignoring this racial and ethnic dimension reduces Venezuela’s crisis to economics alone and misses the point about power and identity in the country.

Now Maduro’s most well-known opponent, María Corina Machado—the recipient of a controversial Nobel Prize—is herself of almost entirely European descent, part Spanish and part Portuguese. She can be referred to as a wealthy Iberian aristocrat. Yet when debates are framed as contests between the ideological Left versus Right divide or clashes between the upper class and the underclass, the racial and ethnic divide is glossed over.

Unlike in North America, people of European descent are not an obvious majority in most of Latin America. With the possible exception of Argentina, the majority population in many countries is of Indigenous ancestry. Until the issue of a racial minority staying in charge of elite, powerful positions is confronted, political crises will continue. This is definitely the case with Colombia,Peru, Ecuador and Bolivia. Brazil has done a slightly better job in dealing with it. But then, only a “slightly” better job.

Chávez and Maduro are not just leftists working up their class base. They also represent a majority excluded from positions of power. This implies that even with the support of the regional or global hegemon, the ricos of Venezuela (Machado included) will not find it easy to assert control. The possibilities of dystopian civil wars cannot be excluded. That is perhaps why the US is not in any hurry to bring Machado into the picture, even if she and her supporters were confident about the same. The US may prefer to make a deal with the Chávez-Maduro followers, just with Maduro excluded. Time will tell.

Jaithirth ‘Jerry’ Rao is a retired entrepreneur who lives in Lonavala. He has published three books: ‘Notes from an Indian Conservative’, ‘The Indian Conservative’, and ‘Economist Gandhi’. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)