While much has been written about the Instrument of Accession signed by Maharaja Hari Singh of Jammu and Kashmir on 26 October 1947, little is known about the nature and purport of the understanding arrived at between Kashmir and Pakistan on 15 August 1947. This understanding is popularly referred to as the Standstill Agreement, even though it was simply an arrangement to maintain the status quo pending the execution of a formal agreement.

The genesis of the Standstill Agreement

The Cabinet Mission’s Memorandum on States, Treaties and Paramountcy, presented on 12 May 1946, envisaged that the princely states could not remain in economic isolation from the rest of India and fresh or modified agreements would have to be negotiated between them and the successor governments in due course. To avoid administrative breakdown upon the lapse of paramountcy, it was considered essential—in the interests of all concerned—that agreements be reached regarding administrative arrangements during the interval between the lapse of paramountcy and the conclusion of new agreements.

The memorandum stated: “During the interim period it will be necessary for the States to conduct negotiations with British India in regard to the future regulation of matters of common concern, especially in the economic and financial field. Such negotiations, which will be necessary whether the States desire to participate in the new Constitutional structure or not, will occupy a considerable period of time, and since some of these negotiations may well be incomplete when the new structure comes into being, it will, in order to avoid administrative difficulties, be necessary to arrive at an understanding between the States and those likely to control the succession Government or Governments that for a period of time the then existing arrangements as to these matters of common concern should continue until the new agreements are completed.”

Since the Memorandum suggested that such arrangements should be on a standstill basis, a draft Standstill Agreement formula was prepared by Edward Wakefield in the political department and circulated on 14 June 1947. Thus, the Standstill Agreement, originally drafted by Wakefield, was a legal instrument meant to provisionally ensure continuity of the existing administrative arrangements until the final agreements were signed between the States and the successor governments.

On 25 June 1947, the Interim Cabinet of the Government of India approved the setting up of the States Department to continue discussions with the Indian States. This department was divided into two parts—Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and VP Menon looked after India’s interests, while Sardar Abdul Rab Nishtar and Ikramullah represented Pakistan’s.

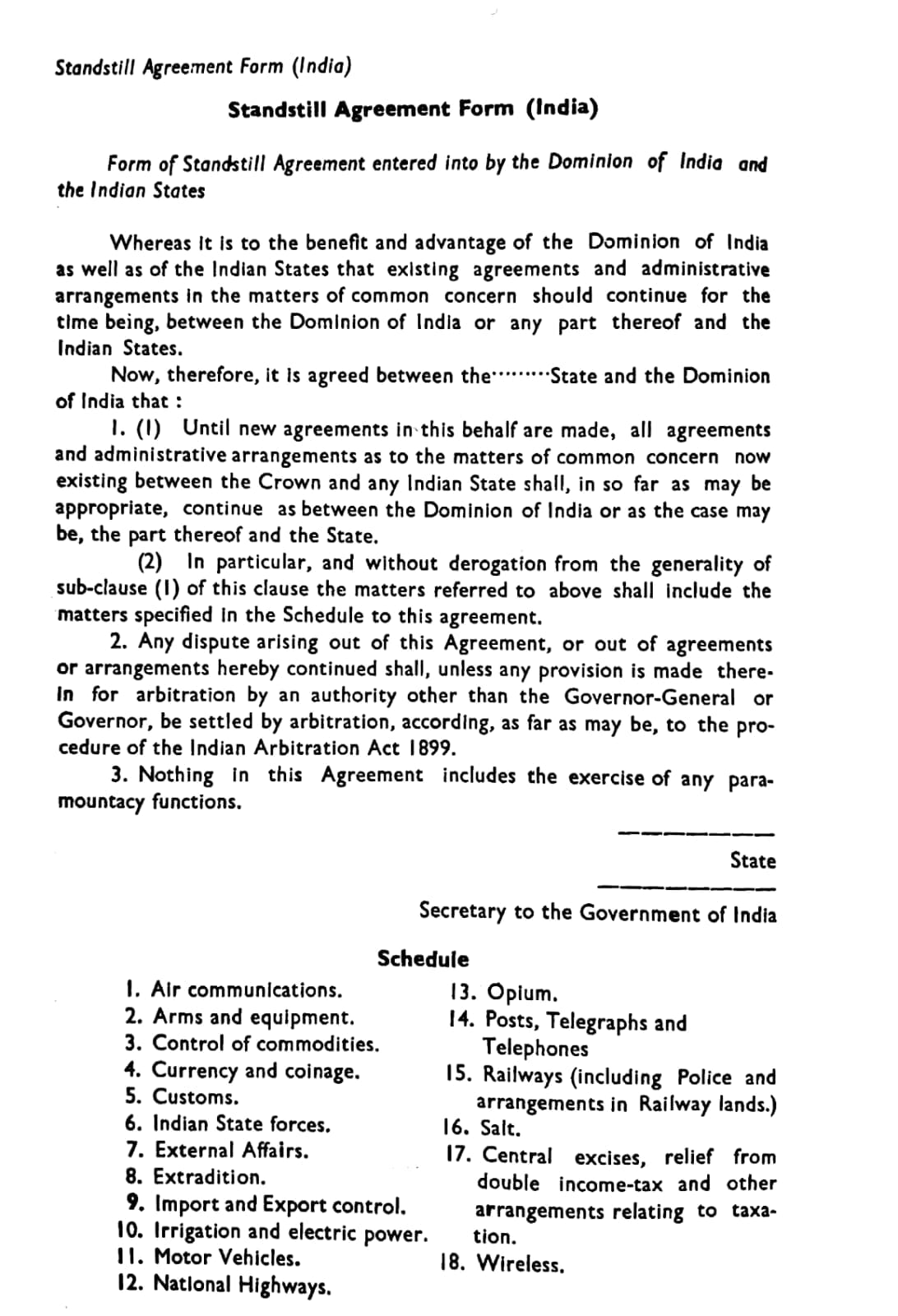

The States Department prepared standard formats for all documentation governing the proposed administrative arrangements between the States and the new Dominions, including a new Instrument of Accession and a revised Standstill Agreement. The drafts were circulated for discussion among the rulers during the special session of the Chamber of Princes on 25 July 1947. These were then examined by the Negotiating Committee, which was divided into two parts—one examining the Instrument of Accession and the other the Standstill Agreement—and were agreed upon, with amendments, by 31 July 1947.

The finalised format of the formal Standstill Agreement (used by India) provided for the continuance of existing arrangement that is, maintenance of status quo on matters specified in the schedule, and expressly provided for arbitration in case of any dispute. Clause 2 of the Standstill Agreement stated: “Any dispute arising out of this Agreement, or out of agreements or arrangements hereby continued shall, unless any provision is made therein for arbitration by an authority other than the Governor-General or Governor, be settled by arbitration, according, as far as may be to the procedure of the Indian Arbitration Act 1889.”

It is pertinent to note that no such Standstill Agreement was executed either by India or by Pakistan with the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

If Kashmir and Pakistan did not execute the Standstill Agreement, then what exactly did the State ‘offer’ on 12 August 1947 and what did Pakistan ‘accept’ on 15 August 1947?

Kashmir’s offer of executing a Standstill Agreement accepted by Pakistan

Consistent with its policy of neutrality, the Government of Jammu and Kashmir announced its intention to sign a Standstill Agreement with both India and Pakistan. Identical telegrams offering to maintain status quo pending the signing of fresh agreements were sent simultaneously by Prime Minister Janak Singh to both Dominions on 12 August 1947.

Wanting to discuss the implications of the proposed Standstill Agreement before accepting the Maharaja’s offer, India requested that a Minister of the State Government come to Delhi for further negotiations. Pakistan, on the other hand, immediately accepted the State’s offer.

Janak Singh’s telegram to Sardar Abdur Rab Nishtar, Minister for States Relations, Pakistan, dated 12 August 1947, read: “Jammu and Kashmir Government would welcome Standstill Agreements with Pakistan on all matters on which these exist at present moment with [the] outgoing British India Government. It is suggested that existing arrangements should continue pending settlement of details and formal execution of fresh agreement.”

Pakistan accepted this offer through a telegram sent by its Foreign Secretary on 15 August 1947: “Your telegram of the 12th. The Government of Pakistan agree to have a Standstill Agreement with the Government of Jammu and Kashmir for the continuance of the existing arrangements pending settlement of details and execution of fresh agreements.”

Nature of the maintenance of status quo agreement

The language of these telegrams is significant. From a plain reading of the State’s “offer” and Pakistan’s “acceptance,” it is clear that the State only expressed its willingness to have Standstill Agreements with Pakistan on all matters on which such agreements existed with the outgoing British Indian Government, while requesting that existing arrangements continue until a formal agreement was executed.

Despite Pakistan’s telegraphic acceptance confirming maintenance of status quo “pending settlement of details and execution of fresh agreements,” no subsequent agreement, as envisaged in the offer and acceptance, was ever signed.

Even though this exchange has been colloquially referred to as the “Standstill Agreement,” even by the parties themselves, it was, in fact, only a preliminary step in that direction and not a conclusive one. What came into existence was at best an agreement to have a Standstill Agreement, as both sides, especially the State expected the formal agreement to follow.

Author Christopher Birdwood also confirms this understanding: “Pakistanis have, I think, been apt to exaggerate the significance of the standstill agreement…In fact no formal agreement was ever signed and the status quo was confirmed only by telegram. A telegraphic agreement was therefore regarded by Pakistan as sufficient to ensure that she stepped into the shoes of the former Government of India in its relations with the State before partition.”

Thus, Pakistan construed the State’s intent to sign the Standstill Agreement as the Standstill Agreement itself. The fact that at least some understanding had been reached with the State made it hopeful that fresh agreements would be signed in due course and full accession would follow thereafter.

Even assuming that this maintenance of status quo arrangement constitutes what is widely perceived to be the Standstill Agreement between Kashmir and Pakistan, it was only a temporary understanding meant to preserve existing arrangements. Unlike the formal Standstill Agreements approved by the Chamber of Princes and executed by India in respect of other princely states, which contained an arbitration clause, this exchange imposed no legal obligation on the Maharaja to execute fresh agreements or to accede to Pakistan.

Nor did it prevent either side from altering or terminating the arrangement unilaterally. This is further confirmed by the fact that the Maharaja had made an identical offer to India. Had India also accepted it, there would have been two status quo arrangements, and the Maharaja would have had to terminate one before deciding the next steps, whether to accede to one Dominion or the other (if at all), without any fetters being imposed on his discretion by the other agreement.

Pakistan’s breach and the end of the arrangement

Muhammad Ali Jinnah expected that Kashmir would “fall into Pakistan’s lap like a ripe fruit,” but this did not happen. As Pakistan became impatient, it decided to pressure the State into taking a quick decision in its favour.

Chaotic conditions in both Dominions had already ruined Kashmir’s timber trade; to this, Pakistan added an embargo on the sale of Kashmir’s produce. Supplies of food, salt, petrol, essential commodities, and even currency for the Imperial Bank’s Kashmir branch were halted by obstructing the only two metalled roads linking Kashmir to Pakistan — via Sialkot and Kohala.

If Pakistan hoped that these tactics would drive the Maharaja towards it, the move backfired. Instead, he turned towards India for assistance and sought to strengthen his State’s linkages with it.

By imposing an economic blockade on Kashmir and later permitting its territory to be used by tribal invaders, Pakistan unilaterally altered the status quo and effectively abrogated whatever “agreement” it believed existed with the State.

Therefore, the contention that the Maharaja could not have offered accession to India because a Standstill Agreement already existed with Pakistan — and that such an agreement imposed a legal bar on unilateral action — is clearly ill-founded. There was never any formal or binding agreement imposing such a restriction between the Maharaja and Pakistan.

The writer is an independent researcher and author of the book ‘Meghdoot: The Beginning of the Coldest War’. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)