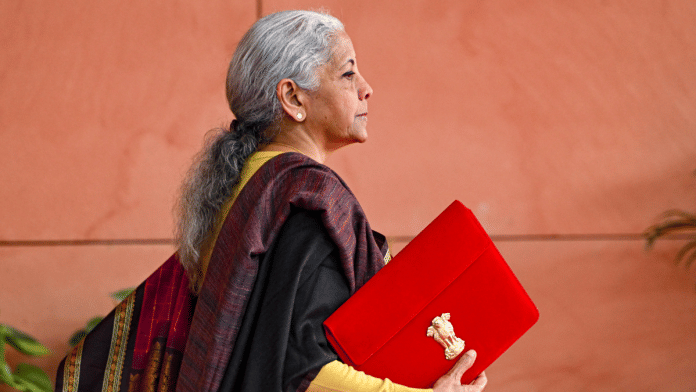

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s announcement of a tax holiday from FY 2026-27 to FY 2067-2047 for foreign companies providing cloud services using Indian data centres has been interpreted as a reassurance to hyperscalers worried about permanent establishment risk. On the surface, that reading is correct.

However, a deeper look reveals that the development masks a more interesting economic dynamic. This measure will reshape the sharing of additional profits across the entire cloud value chain in India, benefiting not just the foreign tech giants, but also domestic data centre operators, Indian resellers, and—in ways often overlooked—Indian and global customers of cloud services.

The Budget 2026 exemption, on the face of it, applies to any foreign company earning “by procuring data centre services from a specified data centre” in India, with an exemption valid till March 2047. On first read, it seems to be a comfort measure for multinational companies such as AWS (Amazon), Microsoft, Google and Meta. Following several Supreme Court of India rulings, these companies feared that locating substantial infrastructure in India would trigger permanent establishment status, thus exposing them to Indian taxation on their global cloud revenues.

But here is the underlying operative constraint—the data centre must be owned and operated by an Indian company, notified under an approved scheme by the IT ministry. And, any sales to Indian customers must flow through an Indian reseller entity, typically the Indian subsidiary of the cloud firm or a domestic partner, which remains fully taxable in India with a 15 per cent safe harbour margin on costs.

What the Budget has done, in other words, is to trade away a potential tax claim on foreign cloud income in exchange for irreversible hard investment on Indian soil. The foreign company pays zero tax on a particular income stream; India ensures that data centre ownership, reseller involvement and domestic value-addition remain tethered to domestic companies, with massive, high-cost infrastructure on Indian soil.

Who benefits, and why the sequencing matters

The primary beneficiary, as intended, is the foreign hyperscaler. AWS, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud and Meta have collectively announced around $67.5 billion of data centre and AI-related investments in India over the next five years. The tax holiday reduces their after-tax cost of using Indian capacity relative to hosting the same workloads in Singapore, the UAE or Europe, making India far more competitive for global cloud workloads.

But the chain reaction begins here. The foreign cloud’s improved after-tax return immediately raises its willingness-to-pay for Indian data centre capacity. In a market where power, cooling and suitable land are scarce—as India races to build gigawatt-scale compute infrastructure—that willingness-to-pay gets reflected in higher lease rates and better contract terms negotiated with Indian data centre operators.

Those operators are India’s emerging infrastructure barons—AdaniConneX (targeting 1 GW capacity), Reliance Jio, Tata group platforms, Airtel’s Nxtra (commanding 15 per cent market share), Yotta Infrastructure, CtrlS, Sify and others. They are racing to create AI-ready facilities across Mumbai, Chennai, Hyderabad, Visakhapatnam, Noida and Pune. The tax holiday does not directly benefit them—they continue to pay corporate tax as usual—but it indirectly bolsters their negotiating position and pricing power by making foreign customers more willing to pay premium rates for access to “specified” notified facilities.

In global data centre markets, lease rates have risen sharply over 2023–2025 because AI and cloud demand have outstripped available power and cooling and, of course, high-performance GPUs. India’s operators, now assured that their primary foreign customers enjoy long-duration tax certainty, can capture a meaningful share of the additional profits generated by this bold income tax holiday through higher capacity pricing, coming on top of India’s ambitious Superconductor Mission, which envisages up to 50 per cent open-ended capital subsidy for domestic manufacturing of GPUs.

Also read: 2026 defence budget is not good enough to achieve Viksit armed forces

The reseller ecosystem and cloud customers

The Budget structure mandates that Indian reseller entities—AWS India, Microsoft India, Google Cloud India, cloud arms of IT majors like TCS, Infosys and Wipro, and telecom-embedded providers—be part of the sales chain when claiming the exemption for Indian customer sales. The 15 per cent safe harbour rules, also a part of this Budget, on related-party data centre service costs signal policy comfort with a layered value chain and protect reseller margins.

Indian and global consumers of cloud services—startups, SMEs, enterprises and SaaS firms—stand to benefit from the competitive intensity that this tax holiday catalyses. As competition among hyperscalers deepens and capacity expands, some of the additional profits will pass through as more competitive cloud pricing, lowering barriers to digital adoption and improving margins for businesses reliant on India-hosted infrastructure.

The political economy of how this is presented matters. Announcing a “tax holiday for foreign cloud providers till 2047 reads as a necessary course correction; announcing what the opposition could frame as “20-year tax holiday for data centre conglomerates like Adani, Reliance and Tata” would draw harsher scrutiny. By routing the direct benefit through the foreign entity while hard-wiring Indian ownership, the government has elegantly packaged a very substantial infrastructure incentive inside a narrative of global openness.

This is a political skill. But it is worth being explicit: the Budget’s measure is as much about anchoring hard assets and Indian ownership as it is about welcoming foreign clouds.

Also read: From populism to productivity—why the Budget 2026 makes a structural turn

Why long-term certainty was necessary

There is, however, a compelling policy case—and indeed, this bold and substantial income tax holiday is quite justified. Data centres are the physical backbone of cloud computing and AI. As workloads grow heavier, hosting capacity within national borders becomes a question of digital sovereignty. India has already moved in that direction through data localisation norms and the Digital Personal Data Protection Act.

The Budget’s tax holiday is a fiscal complement to that regulatory thrust: it says to foreign clouds, “Bring compute and workloads to India; we will not use the tax system to ambush you”—but Indian ownership and domestic intermediaries remain non-negotiable.

Viewed this way, the measure is not a disguised giveaway but a conscious, well-crafted and necessary concession: India forgoes contested tax claims in exchange for encouraging irreversible hard investment, in the order of billions of dollars, on Indian soil. That is reasonable for a country betting on becoming a global cloud hub and a centre of AI capability.

The winners are multiple: foreign hyperscalers gain tax certainty; Indian data centre operators gain pricing power and volume; Indian resellers gain regulated margins and market growth; cloud customers gain access to cheaper, more competitive services anchored in India. It is a policy that aligns incentives across the entire value chain while preserving domestic ownership and taxable profit pools.

The packaging is clever. The economics are sound.

KBS Sidhu is a former IAS officer who retired as Special Chief Secretary, Punjab. He tweets @kbssidhu1961. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)