Ratan Tata’s least acknowledged and biggest contribution has been merging social entrepreneurship with business in Assam. Through his work in the state, he showed that he could take a distant part of India, the Northeast, and truly integrate it with the rest of the country. His leadership in public-private partnerships is laudable.

As we got to know Mr Tata in a personal capacity, we realised that his commitment to Assam and the Northeast stemmed from his friendships with people from Darjeeling and Bhutan. He would often recall a funny anecdote about Lendrup Doji (Lenny), his Bhutanese best friend who he studied with at Cornell University. Lenny owned a fast car and attracted the most interesting companions, which helped Tata realise the significance of quality automobiles. Lenny then said to him: “If you want to make truly great cars, especially sporty ones, you need to understand the importance of consumers and the people who accompany them.”

I remember meeting him a few times and he was passionate about education and healthcare. He called education “absolutely vital and critical”, and spoke about the necessity of establishing a Tata trust and scholarships in the region. He even brought the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) to Assam with the larger goal of aiding the progress of the Northeast.

TISS, established in 2010 in Guwahati, was a huge success. More importantly, it was proof of Tata’s ever-evolving vision of social entrepreneurship. He suggested including Bhutan, Bangladesh and Myanmar in the curriculum to invite exchange students and teachers from those countries, to help increase engagement and welcome applicants from beyond the Northeast. On average, 250 students graduate annually from TISS, and over 2,000 students from all the Northeastern states have participated and successfully completed their education there. This exemplifies true integration within the Northeast.

Ratan Tata was a differentiator, doing things that were out of the book. He believed in balance – everything should make money so that it can be taken forward. This was especially evident in how he approached the Tata Tea venture in Assam. The company had been consistently incurring losses – upwards of Rs 200 crore over the last few years. He believed that every initiative should generate profits, not losses, to ensure sustainability. His philosophy was that his company should not operate at a loss and that perseverance is key to reversing such a trend. He emphasised the importance of focused work in turning the situation around and ensuring long-term sustainability, creating sustainable livelihoods while making the business viable.

Despite these difficulties, Tata stood firm against suggestions to abandon the venture. He understood that Tata Tea wasn’t just a business—it was a lifeline for over 33,000 workers and 200,000 people, if you included these employees’ families. Tata believed that beyond financial profit, businesses had a responsibility to the communities they served. So, he responded with innovative solutions. He decided to upskill the workers at Tata Tea and expand into new areas. He diversified into crops like pepper and even ventured into flower cultivation. Although the flower initiative didn’t succeed due to supply chain and market challenges, pepper became a valuable addition to the company’s amalgamated plantations, showcasing his foresight in crop diversification.

Ratan Tata’s other significant initiative was skilling people at the grassroots level through Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs), a programme in which I had the privilege of playing a key role. The government’s ITI program was fledgling in the early 2000s and lacked relevance. However, Tata introduced modern technology and training methods, including a cutting-edge driving programme where an automated car simulator (equipped with computers at the front) taught people how to drive in just seven days.

This idea came from his experiences with Lenny at Cornell and his general passion for automobiles and we began implementing it in many ITIs and polytechnic institutes leading in electronics. In 2005-6, this method not only created trained workers and ample employment opportunities but also produced skilled – and the very first – women drivers in the state’s Nagaon city. Absolutely revolutionary.

He then set out to expand the hotel division of his business and optimise the tourism sector. Tata launched the budget-friendly Ginger Hotels, strategically located next to the Institute of Hotel Management. His vision was to recruit students from these institutes, train them, provide employment, and eventually integrate them into Tata’s broader hotel portfolio. This initiative played a pivotal role in revolutionising how the Northeast became a vital source of labour for India’s hospitality industry. But this was just the beginning.

His colleague RK Krishnakumar played a pivotal role in driving various initiatives with him focused on skilled employment, leveraging his extensive experience and leadership to create impactful programmes. Their support was crucial in establishing training platforms that empowered communities with the skills needed to thrive in emerging sectors such as tourism.

Also read: Ratan Tata mettle revealed in 1980s’ PepsiCo battle. Shook up fuddy-duddy business practices

Unwavering commitment to Assam

An incident with the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) and Tata Tea shows the complex challenges Tata tided over in Assam, balancing social responsibility and security concerns. ULFA, a separatist group advocating for the state’s independence from India, had significant influence in the region at the time. Things took a turn for the worse when the Bodos kidnapped the son of the first chief minister of Assam, Gopinath Bordoloi. Bordoloi’s son used to work at Tata Tea. It was after this, in 1997, that Ratan Tata was also accused of helping and supporting the ULFA.

Tata, however, denied these allegations. According to him, the company had not provided any financial help to the insurgents. It had only extended medical aid at the Tata Referral Hospital in Chabua, which was a non-surgical hospital that only catered to basic healthcare needs.

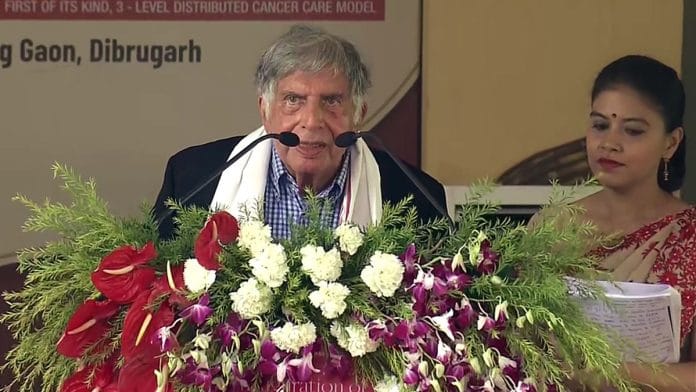

Under the leadership and vision of Ratan Tata and the state’s chief minister, the Assam Cancer Care Foundation was established with the objective of bringing critical cancer treatment to the people of Assam and the Northeast. With 17 hospitals and over 2,000 beds, this revolutionary initiative ensures that no patient has to travel more than three hours to receive diagnosis, care, and treatment. By addressing this significant gap in healthcare, this collaboration has transformed the region’s access to cancer treatment, marking a new era in public-private leadership.

To reach all states, non-governmental organisations such as the Assam Investment Advisory Society, The Centre for Microfinance and Livelihood, and the North East Initiative Development Agency are set and have impacted more than 100,000 households and over 200,000 individuals, focusing on livelihood and self-employment opportunities.

Tata’s vision for Assam was to integrate international trends, culminating in one of the most significant announcements in recent years, the establishment of a $3.5 billion semiconductor industry in Jagiroad. He said: “If you don’t keep up with the times and train people, you will never be able to integrate them. Keep their culture, keep their society alive while doing this.”

It was the Chairperson of the Tata Group, Natarajan Chandrasekaran, and CM Himanta Biswa Sarma, whose dynamic and futuristic vision for the state helped implement the plan. Over the next five to 10 years, the state is expected to go beyond agriculture and oil to become a technology hub. The project will require extensive training and is anticipated to employ 15,000 people directly, with over 100,000 in the region benefiting indirectly. This initiative marks a transformative shift in Assam’s economy, bringing increased global employment opportunities.

Tata wanted to do something different to integrate Assam into the rest of the world. And that, really, is his lasting and final contribution.

Ranjit Barthakur is a social entrepreneur and chairman of Tata’s Centre for Microfinance & Livelihood (CML). Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)