A few days ago, major media houses posted a video on their social media channels of two donkeys being forced to pull a large SUV. At first glance, it resembled the old theatrics of political protests where donkeys are used as objects of humiliation or ridicule though the word of law restricts such performances. It turned out that an aggrieved vehicle owner had paid the owner of these two donkeys to stage a dramatic protest after his new car malfunctioned.

The visual was distressing, cruel, and wholly unnecessary; it was in violation of established law. Under the Draught and Pack Animals (Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) Rules 1965, a donkey may only carry a pack load of up to 50 kg. Here, each donkey was forced to haul more than thirty times that limit. Undoubtedly, the Thar owner was entitled to protest defects in his vehicle and the service he received or the lack of it; what he was not entitled to do was externalise the cost of his outrage on another vulnerable species. We must ask whether our moral instincts extend beyond our own convenience.

This incident reveals two long-standing patterns: Our deep apathy toward animal suffering, and our reflexive disregard for laws that do not seem to directly benefit us. What is most obvious is how India’s relationship with animals is full of contradictions. We revere certain animals (symbolically only, their exploitation warrants a book), while reducing most others to instruments of labour, entertainment, food or emotional expression and more. The donkey embodies this paradox, mocked as a lazy dimwit, yet exploited relentlessly for labour or spectacle. And this is merely one example; all non-human animals are casualties of this normalised objectification.

The most distressing part? This incident only elicited shock and disdain from viewers because it was recorded, amplified, and aestheticised. Cruelty against animals in India has become so ordinary that only when it is viral does it command our attention.

This mindset is visible not only in sensational viral clips but in the violence we collectively underwrite every day. The phrase “beasts of burden”, is rooted in colonial and pre-colonial legal and economic vocabulary, and reflects a worldview that sees certain animals solely through the prism of their labouring utility.

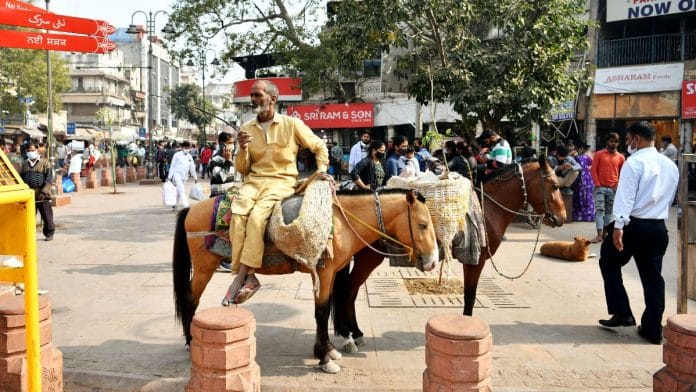

Unfortunately, that perception persists in modern India. On pilgrimage routes such as Vaishno Devi, the Char Dham (Kedarnath, Yamunotri, Gangotri, Badrinath) and tourist locations like Matheran, ponies, mules, and horses are pushed to exhaustion ferrying pilgrims/tourists by day and hauling construction materials up steep, dangerous slopes by night. For weddings, grooms are sat astride horses which are buried under decorations and surrounded by deafening bands, fireworks and blinding lights. Every day we pass by these breathless, injured animals without batting an eye. Their suffering has been absorbed into the landscape.

The incongruity is stark: People undertake spiritual journeys, go on holidays and start new lives, all while paying for the infliction of cruelty on animals that is so contradictory to every religious philosophy and our fundamental values.

The Pune incident, then, is not an anomaly but a singular publicised instance of the cruelty we justify every day.

Also read: Indian laws are letting animals down every day. It’s a legal, moral, ethical issue

Change the laws

More importantly, the episode spotlights the structural weakness in our jurisprudence, one that we have acknowledged but neglected to act upon for decades now. The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1960, which replaced the colonial PCA Act of 1890, which defined cruelty so narrowly that pain inflicted out of public view did not constitute an offence. Then, the Courts routinely upheld this limitation. In one infamous case, when the eyes of a Saras crane being transported by train were sewn shut it was held not to be “cruelty” because the act was done prior to transport and not in public view; a chilling illustration of how law and morality were once confined to visibility rather than suffering.

On paper, India has progressed since: The PCA Act 1960 took a more holistic view of cruelty, prohibited unnecessary pain in all contexts, and later rules like the Draught and Pack Animals Rules attempted to codify safeguards for working animals. Sadly, the law is dated, and still has a long way to come. For over a decade now, organised efforts have been made to demand an amendment to the PCA Act, in order to give effect to its purpose i.e. prevention of cruelty.

As we clamour for the law to continue to evolve with the times, we must hold ourselves accountable to internalise and act upon our humanity. The underlying values on which our constitutional morality rests must permeate societal attitudes. In Animal Welfare Board of India v. A. Nagaraja (2014), the Supreme Court observed that animals possess intrinsic value and dignity, independent of their utility to humans. While sections of this judgment have been set aside, the observations of the Apex Court certainly stand.

However, the social response to cruelty hangs on spectacle, rather than being anchored in principle. Outrage arises only when cruelty is dramatic enough to trend. The everyday suffering of countless animals remains invisible because it is familiar.

India celebrates technological prowess, electric mobility, lunar missions, all while tolerating medieval treatment of the animals that work, live, and suffer alongside us. The mismatch between our material advancement and the moral stagnation is not defensible.

The Pune donkey incident is a mirror. It reflected a society where animals are seen as tools, where cruelty passes without objection unless recorded, and where legality is invoked only when virality demands action. If we intend to call ourselves a humane society, compassion cannot be occasional and selective.

The outrage will fade, as all viral moments do. What must endure is the political and civic will to correct a system that allows this cruelty to be the norm. That requires stronger penalties, consistent enforcement, and a societal shift that recognises animals not for their utility but for their intrinsic worth. Ultimately, the measure of our progress will not be the sophistication of our technology or the height of our buildings, but the depth of our empathy. A society that ignores suffering because it is commonplace is a society that has lost sight of its constitutional values. Recognising this and acting on it is the truest test before us.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Fuck off these animal bond lovers ..

You only lamenting on this type of scenic visuals… Go and have a protest on slaughtering during various festivals in which no heart melting feelings shown towards mass slaughterings of animals…. You too bloody observers relish the dishes of the same…..

Me and my friend once pushed a thar 1.5 km. It wasn’t easy but wasn’t that extrem to call it a cruelty and Donkeys are much more stronger than humans.

Pulling car is not same as lifting it. As a human, even I can pull a small car. So 2 donkeys can easily pull that SUV.