Where there is war, there is also a fog of war. In India, what used to be boring matters of statistics have now become the focus of great controversy. A war for hearts and minds is being fought, in part, through statistics — by either disregarding them or deploying them, as the case may be.

The stewardship of the economy may not be the primary focus of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) appeal, but economic failures would undermine its claims, based as they are on all-round triumphalism. Economic stewardship is an important and possibly essential prop for constructing an electoral majority, even one centred on identity politics and political division. There cannot be an Amrit Kaal, let alone Viksit Bharat that it is supposed to usher in, without widely shared economic prosperity. Economists may be “yes men in the halls of political economy” — as the Nobel Prize-winning economist Theodore Schultz called them — but quite a number of India’s economists do one better—cheerleading a ‘rah-rah’ chorus.

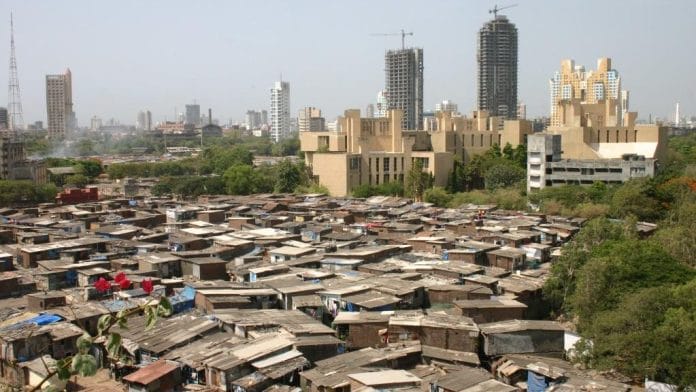

Although there are debates regarding many of the current government’s claims, including about whether India has achieved as rapid growth as it claims, the fog of war is nowhere more present than in the arguments about poverty estimates.

Growing confusion

At one point, India was the leading developing country to create a statistical system that monitored living standards and was also the first to establish a widely accepted poverty line. The concept was so influential that it became the reference point and primary basis for the World Bank’s earliest international poverty line developed in the late 1970s. But today, there is rank confusion. A Martian observer would not know what to think, as one would be faced with vastly opposing perspectives, bookended by the pronouncements of Surjit Bhalla and Utsa Patnaik. One argues that extreme poverty has been eliminated in India, while the other maintains that the vast majority of the Indian population is still poor. These various and often starkly opposing views thrive in the confusion enabled by the suspension of official income poverty estimates after the replacement of the Planning Commission by the NITI Aayog in 2015.

But confusion grew over the last decades as the poverty line for India previously thought suitable lost influence due to phenomena such as ‘calorie drift’ — in which people consume fewer calories but in new forms — and by changes to statistical methodologies, which led to endless debates about comparability. A series of official committees consisting of distinguished economists and administrators tasked with alleviating the confusion only added to the problem—not least through Alice-in-Wonderland reasoning, such as that provided by the committee chaired by Suresh Tendulkar. The committee held that a suitable poverty line for urban areas (in turn used to anchor the poverty line for all of India) would be the one that happened to produce similar urban poverty estimates to those generated by the prior poverty line. As if one could derive the question from the answer!

The solution to the rot was not a fresh approach, but patch after patch placed upon the old one. Unfortunately, such an approach based on a careful reconsideration of concepts and methods has been lacking due to the premium on scoring points. NITI Aayog’s recently released National Multidimensional Poverty Index, which highlights the service-delivery attainments of the government without addressing whether incomes have been rising, has added to the confusion, employing shortcuts and extrapolations to allow the government to claim victory just in time for the Lok Sabha election. If that were not enough, the government recently released a ‘factsheet‘ of the Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES) 2022-23, which declares, too, that poverty has fallen sharply — but the study depends on new methods that are insufficiently explained and have left experts reserving judgement.

Also read: Is India’s ‘growth story’ a sign of its strength or world’s weakness? China holds the answer

New weapons in the war

As the public relations war continues, with the aid of an apparently increasingly pliable statistical administration, one thing is now clear — claims about poverty have become weapons in this war, with little pause either to enquire into the experiences of ordinary people or to consider “the indignity of speaking on someone else’s behalf” that is entailed in making bold claims about the lives of people for one’s own purpose.

Strategic obscurantism, false precision, and ever-changing conceptions of what we are to measure, if we are to measure at all, produce mounting confusion, except among the partisans who launch statistical missiles. Some are confident in their own facts; others find none. The Martian would be forgiven for concluding that there is, in India, a free-for-all.

Vikram Seth said it best:

On the obnoxious dreary pillage

Of privacy, imperfect knowledge

Will sprout like lodged rice, rank with grain

In whose submerging ears obtain

Statistics where none grew before,

And housing estimates galore…

But statistics are not whatever we want them to be. They are a map to guide our choices lest we do the wrong things or fail to do the right ones, do them too little or too much, too early or too late. We might heed Seth again:

O needful numbers, and half true,

Without you what would nations do?

India, once a pioneer in the collection of statistics, is on course to find out.

The author is an economist at the New School for Social Research, New York. Follow him on X @sanjaygreddy. Views are personal.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)