Like most parents, Blessy Mathai, who has two sons with Intellectual developmental disorder and on the autism spectrum, hasn’t caught a break since schools were closed in March 2020. The Chembur-based homemaker spends almost all of her time assisting her sons with their day-to-day activities.

“Initially, Ethan would not sit for therapy at all,” Mathai recalls. “Or, he’d sit for 10 minutes, then want to move. My younger son, too, didn’t take to zoom schooling immediately, and it was difficult to care for both of them at once, as Ethan needs assistance with everything, even to use the bathroom.”

A developmental disorder is a group of conditions caused by an impairment in physical, learning, language or behaviour areas. These conditions begin during the developmental period, may impact day-to-day functioning, and can last through a person’s lifetime. Children with a developmental disorder could have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, fragile X syndrome, cerebral palsy, intellectual and developmental disability (IDD), vision impairment, muscular dystrophy and others. Levels of disability vary depending on the severity of the disorder; while some may be fully able to perform all activities of daily living, others, like Mathai’s 12-year-old Ethan, may require substantial support.

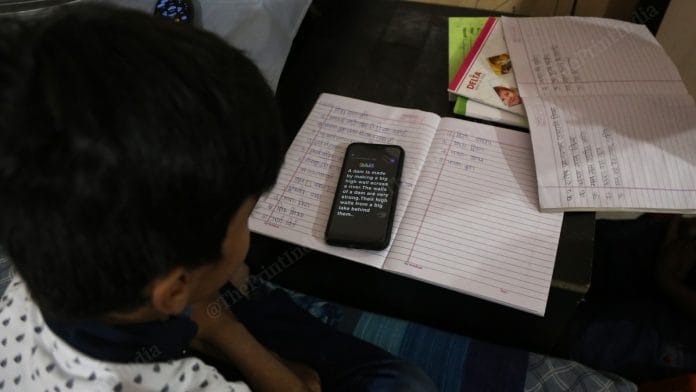

Before the pandemic brought the country to a grinding halt, Ethan attended The Jai Vakeel Foundation, that works in the space of IDD, in Parel, five days a week, where he received both academic as well as therapy that supported his ability to both perform at school and function independently in daily life. Ever since schools were closed, it has fallen upon his mother to help him pay attention to and follow the instructions of the teachers on screen.

It’s been just as challenging a time for homemaker Ratna Joshi, who has two neurotypical sons aged seven and nine. Breach Candy-resident, Joshi, says, “Some days, it’s particularly hard to get the boys to focus on the on-screen class. It doesn’t help that their routine has gone for a toss completely, and that they’ve grown used to spending so much time on electronic devices through these months. I can’t wait for schools to resume.”

Also read: Obesity, psychological trauma — why experts say it’s high time we send kids back to schools

Missing out on the support system

Now in its 17th month, the Covid-induced lockdown has been very hard on parents. Attendance data reveals that the initial enthusiasm with which parents rose to the challenge of supporting their children through online instruction, has waned. Paediatric neurologist Dr Anaita Hegde is sympathetic. “Parents are utterly exhausted,” says Dr Hegde.

Parents of special needs students, like those of very young children, face an additional challenge as the anxiety of their ward often manifests in ways they cannot decipher. “Besides, many of these families are also grappling with personal loss, and reduced incomes,” says Dr Hegde.

Aside from weighing them down with additional duties, the closure of schools has also deprived parents of the comfort of social support systems. Ujwala Bhagwat, whose 13-year-old Ishwari has cerebral palsy, says, “It’s reassuring for us to meet other parents whose experiences are similar to ours.” Bhagwat also points out that “socialisation becomes easier for our children at school.”

Surveys conducted in the US and several European countries by American NGO Save the Children, in 2020, revealed that social restrictions and school closures had resulted in almost one in four children reporting “feelings of anxiety”, and that “many (were) at risk of lasting psychological distress, including depression.”

“Children learn through play and when they interact with other kids. They build language and communication skills, learn to use toys with one another, how to have socially appropriate exchanges, like when they sit and have a snack with someone…these are very meaningful experiences for kids,” says Dr Roopa Srinivasan, director, developmental paediatrics, Ummeed. “Along the way, they’re learning to be independent, learning to eat by themselves, learning to ask to use the washroom…to listen to instructions. Schools establish routines for kids, the absence of which can be distressing for many, especially those with autism. Routines contribute to a sense of stability and control.”

Jo Chopra McGowan, executive director of Latika Roy Foundation, which provides education and social services to children who are disadvantaged by disability and poverty, adds: “A whole set of habits get formed [when students stay out of school] and it’s very difficult to get them back to speed”. While Chopra believes the lockdown has also given parents a chance to notice their child’s inner resources, “and in many cases children seem less stressed,” online schooling, she says, poses huge challenges for special needs educators. For example, while physical and occupational therapists have been using cameras to convey instructions to parents, “parents may not understand the names of muscles, or they may be unable to get the child to perform the particular action,” says Chopra. “Therapists struggle, too, as they are trained to get the children to perform the action, but not trained to describe it in such a way as to instruct someone else to do it.”

Besides, certain strategies that enable teachers to better engage with special needs children can’t be used across a screen. “A teacher can’t make a child sit directly in front of him or her, for example, or use the multisensorial approach that’s most effective for some children with special needs,” says child and adolescent psychiatrist Zirak Marker, who serves as the medical director at the Aditya Birla Integrated School. Though many schools, such as his, were quick to innovate to overcome most hurdles, Dr Marker shares that experiential or activity-based learning is especially effective with special needs students, “and with virtual learning, that gets taken away”.

Also read: India’s online classrooms are outdated for disabled kids. Covid just made it worse

Getting back becomes difficult

Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) techniques – used for not just those with autism spectrum disorder, but for those with attention deficit disorder, speech and language impediments, obsessive/compulsive disorder, and so on – requires assessing a student’s body language and that, too, becomes harder to do in a virtual classroom. Somatisation, regression and loss of speech are just some of the consequences for children, Dr Hegde points out. “Though as an organisation, we have risen to meet the needs of our students and have re-envisioned our normal milestones as well as innovated with teaching techniques in response to the challenges of online schooling, children with special needs are best served by in-person instruction” adds Archana Chandra, CEO, Jai Vakeel Foundation. She fears that continuing with online instruction will only exacerbate educational inequities.

Not to mention, the longer students stay out of school, the harder it becomes for them to return, “because of co-dependency with virtual platforms or with their parent/s,” Dr Marker explains. “Children with sensory issues may also take a long time to get used to other children touching them,” he adds.

Parents such as Ujwala Bhagwat fear exactly this. “The more time our children spend at home, watching TV and on their mobile phones, the more their critical skills take a beating,” Bhagwat says, urging the authorities to treat the re-opening of schools as a top priority. According to a recent UNICEF calculation, the learning loss associated with school closures around the world will cost the estimated equivalent of $10 trillion in these children’s future earnings. Given that the Lancet Covid-19 Commission India Task Force noted that only 24 per cent of Indian households have access to internet facilities, the loss of learning and its enduring impact here will be significant.

“We could run more batches for fewer hours with fewer kids in each batch, to ensure social distancing,” offers Dr Srinivasan, who, like most experts, believes it’s time for the state to chalk out a plan to re-open schools. “Even if schools can only stay open for a short while [in the event of another wave of the pandemic], it’s worth a try,” she says. Dr Hegde, too, feels, “We now know how to manage this [Covid-19], so it’s time to take necessary precautions and re-start life.”

Anjana Vaswani is a senior journalist and award-winning author. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)