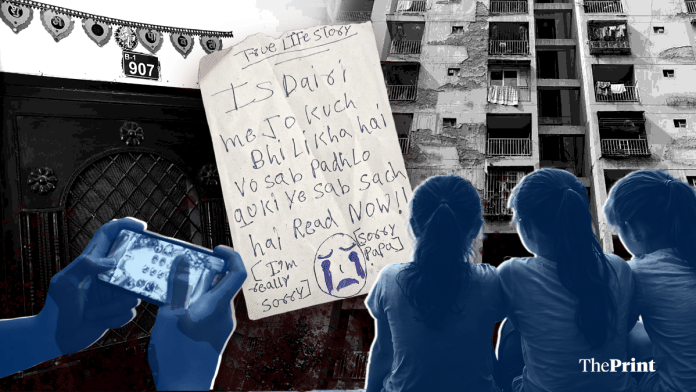

For three teenage sisters, reality was not their two-bedroom apartment in Ghaziabad but a digital Korea they escaped into through series, songs, and online games. Their ‘suicide note’ suggests that their fatal jump from a ninth-floor window ledge this week came shortly after their parents’ attempt to cut them off from that world.

“We didn’t love you family members as much as we love Korean actors and K-pop groups…You never understood how much we loved them (Koreans). Have you seen the proof now? Do you now believe that Korean [culture] and K-pop meant the world to us?” read a page in the diary recovered by the police.

Headlines such as ‘K-Pop fantasy turns fatal’, ‘Korean content influence suspected’, and ‘Ghaziabad sisters die over Korean love game obsession’ were splashed across news pages and social platforms. Clips were shared of their father, Chetan Kumar, calling for the government to ban Korean dramas and videos in India.

What began as a localised tragedy quickly spiralled into a national argument about Korean content, its growing popularity among young people in India, and whether it had pushed the sisters over the edge. This is why India’s K-Wave ‘addiction’ is ThePrint’s Newsmaker of the Week.

However, police investigations into the deaths of the three sisters—aged 16, 14, and 12— also revealed a life of profound isolation: no schooling, minimal contact with people outside the home, and an overcrowded household strained by debt, bigamy, and conflict. While Korean shows are often loved for their escapism, the urgency of the escape itself for the girls has become evident as more details have come out.

What was the trigger?

The three sisters allegedly jumped to their deaths, one after another, from their ninth-floor flat in Ghaziabad around 2 am on the intervening night of Tuesday and Wednesday.

Initially, it appeared that the sisters had taken the extreme step due to an “addiction” to online task-based games. There was speculation that they had died at the last stage of a game, not unlike the infamous Blue Whale some years ago. Attention also turned to ‘Korean love games’, in which users pose as Korean men or women to interact with virtual partners. It seemed plausible, given that ‘mobile addiction’ has previously been cited as a trigger for self-harm or even violence, though such cases are rare.

Reports suggested that their father had taken away their mobile phone a few days before the incident.

“The three sisters were strongly influenced by Korean culture, which included songs, movies, TV shows, as well as overall pop culture. When the family understood the magnitude of this influence under which they had started inhabiting Korean culture, they barred them from using mobile phones around five days back,” Ghaziabad Trans Hindon DCP Nimish Patil told ThePrint.

Yet, though the girls were indeed obsessed with K-culture and even went by ‘Korean’ names, their writings also pointed to troubled lives at home. On the walls, they had written lines such as “Make me a heart of broken” and “I am very, very alone, my life is very very alone.” Another entry from their diary framed a sense of disconnection from the family: “…we are Korean and K-Pop and you are Indian and Bollywood.”

Police say the sisters were living in near-total isolation even though nine people shared the two-bedroom flat: the father; his two wives, who are sisters; another sister of the wives; and five children. The 16-year-old girl who died on Wednesday was the eldest. The 14-year-old and 12-year-old were from the second wife.

The father, who, according to his own admission to the police, could not make enough money to send them to school, was the lone breadwinner. A stock trader, he is said to be under severe debt.

With no formal education or structured daily routine, the girls had little interaction with the world outside the home, police said. They filled that vacuum with digital content consumed on phones.

Over time, the sisters even started speaking to each other in Korean and reportedly ran a YouTube channel under their ‘Korean’ identities, which their father is said to have deleted. In their note, they also mentioned that they wanted one of their younger siblings to adopt Korean culture, which led to friction with one of the mothers in their house.

Sources familiar with the investigation said the sisters’ final writings also expressed fear of being married off to Indian men— a threat supposedly issued to them by their father. “You expected our marriage to an Indian, that can never happen,” read one line. Some of the notes hint at physical violence as well: “Death is better for us than your beatings.”

Also Read: Manipur to Ghaziabad — why Indians are drawn to K-pop

Did K-culture lead to the deaths?

In the days after the deaths, Korean pop culture became the easiest explanation. The sisters’ immersion in K-dramas, music, and online content was almost treated as the reason they had died, that they chose to give up their lives instead of giving up the lifestyle.

Escapism through Korean shows, however, is hardly unusual in India, especially among women. Manisha Mondal wrote in ThePrint about her own ‘addiction’ to shows such as No Tail to Tell: “It does offer an escape from the drudgery of everyday life—by presenting an unachievable kind of love… If Shah Rukh Khan set the benchmark for romance at 20 per cent, K–drama heroes exceed 100 per cent.”

Followers of Korean culture argue that much of the Indian entertainment industry relies on hyper-masculinity and heightened emotions, including violence and abuse. Such shows, they say, rarely offer viewers a soft landing into an aspirational world.

The timing of the sisters’ withdrawal from school also coincides with the period when Korean content began to reach a wider Indian audience. As Tina Das wrote in a recent article, mass appetite for Korean storytelling “changed decisively after 2020”.

With rising digital access and regional dubbing, K-culture has become a sticky entertainment phenomenon here too. Even the food, which previously may or may not have appealed to Indian tastebuds, has found a foothold. Back in 2024, ThePrint counted around 30 Korean restaurants and eateries across Delhi-NCR.

Simply put, the appealing aesthetics and softer tone of Korean content across genres allows viewers to imagine lives different from the ones they are actually living.

Given the details that have emerged in the police investigation, though, the Ghaziabad suicide case is less about the perils of an imagined world than about how little the sisters had in their real one.

Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

So these people want to ban it now ? Why do we have to react so hard on everything ? Read the case – this was so abnormal by all standards.

The fact of the matter is people and especially teenagers can get obsessed with things. Most parents need to handle such obsessions with early intervention.

Let’s be honest we also have a culture of celebrity obsession as well, so would we ban our stuff if someone kill’s themselves on similar grounds ? We have to be smart about how we deal with these things.