Akbar The Great Nahin Rahe” is a Hinglish play directed by Sayeed Alam of the theatre group Pierrot’s Troupe. The title is a play on words with a dual meaning — Akbar the Great is no more, and Akbar is no more great. But was he ever? If yes, who made him great?

Certainly not the Muslims. In popular culture, they refer to him not as Akbar-e Azam (Akbar the Great), but as Akfar-e Azam (Kafir the Great). He has been the bête noire of Muslim political discourse in India — for seeking to broaden the foundations of Muslim rule by accommodating Hindus in the system, and for trying to build a spiritual and ideological framework around this vision through the syncretic order called Din-e Ilahi (Divine Faith), and the policy of Sulh-e Kul (Universal Amity).

He practiced what he preached. His appreciation of Hinduism and other non-Islamic religions was evident as much in his statesmanship as in his personal belief and behaviour. To the Muslims, this amounted to heresy, blasphemy, and apostasy. They rose in rebellion, and the sword they drew against him still remains unsheathed. The jihad against Akbar — the infidel, the apostate — continues unabated.

But more on that later.

Also read: Why highly placed Muslims became ‘Krishna bhaktas’ in the Mughal period

Who bestowed greatness on Akbar?

This article began with the question: who made Akbar “The Great”? It’s important to ask, because apart from Alexander and Ashoka, Akbar is the only king for whom this appellation has virtually become part of the name.

I couldn’t find who used this label first, but the title of Vincent Smith’s Akbar: The Great Mogul (1917) seems to have played a seminal role in popularising the epithet and creating a historiographical cult around the Mughal emperor. But the ascription of greatness wasn’t just a British invention. It was, actually, an Indian (read: Hindu) show of magnanimity towards the memory of a king who, despite his limitations — and occasional slide into brutality, such as in Chittor (1567–68) — was a hundred times better than the rest of Mughal and Sultanate rulers.

That said, it raises a disturbing question: how oppressive was Muslim rule that Akbar — under whom Hindus got some relief, though no equality and much less any precedence, as the polity remained foreign with the overwhelming preponderance of Irani and Turani nobility — came to be regarded as great? It raises a further question: should this solitary example of Akbar be used to whitewash the crimes of a polity that reigned for centuries?

Hindus made Akbar great

When Vincent Smith’s book was published, Lala Lajpat Rai reviewed it for Political Science Quarterly, an American journal. Rai was one of the Lal-Bal-Pal triumvirate (with Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Bipin Chandra Pal), which not only led the extremist faction of the Indian National Congress but also believed in Hindu nationalism. In his own words, Rai was “wedded to the idea of Hindu nationality”.

The very first line of his review reads: “Akbar the Great Mogul was by common consent one of the greatest monarchs known to history.” He glorified the monarch even though the book under review vividly described the Chittor carnage — thirty thousand Hindus slaughtered, hundreds of women committing Jauhar, and numerous temples destroyed — all confirmed by Akbar’s own Fathnama (proclamation of victory) dated 9 March 1568.

Yet, Rai wrote, “Mr. Smith… at places is unduly hard on him (Akbar), forgetting the times in which he lived and worked.” He could not have said this unless he was convinced that Akbar later made sincere efforts to amend his past wrongs. In a rare gesture, Akbar honoured the gallant defenders of Chittor — Jaimal and Patta — by installing their statues, mounted on elephants, at the Agra Fort gate.

James Tod writes in the Annals of Mewar: “He (Akbar) finally succeeded in healing the wounds his ambition had inflicted, and received from millions that meed of praise which no other of his race ever obtained.”

Also read: Each day brings some new horror and hate. Worrying that ordinary Hindus aren’t so shocked

The imperative of reconciliation

Truth brings reconciliation and contrition brings closure. Those who try to hide the bad and the ugly of the past should learn from Ashoka and Akbar about honest disclosure and sincere reconciliation. In the Indian tradition, Pashchatap (remorse), Prayashchit (atonement) and Kshama (forgiveness) — in that order — have been the values of highest morality.

Every wound can be healed and every conflict can be resolved through truth and reconciliation. But to seek reconciliation, one has to see the need for it. So, the question is: do the Muslims have the moral compass and ideological conviction for peaceful coexistence with other communities, or are they still trapped in their medieval mode of thinking in which Islam is perpetually at war with other religions?

Do Muslims consider Akbar great?

The Muslim attitude toward Akbar is a good pointer to their groupthink. While they admire his empire-building achievements, they don’t have the ideological framework to appreciate the philosophy behind his actions. Many wish he had remained as steadfast in Islam as his great-grandson, Aurangzeb.

Contrary to both common sense and academic consensus, they blame the fall of the Mughal Empire on Akbar’s liberalism rather than Aurangzeb’s fanaticism — which forced the Indian masses to rise in revolt and bring down the mighty empire. In their eyes, Akbar — despite being the true founder of India’s grandest Muslim empire — was a renegade from Islam, whose policies weakened the foundations of the Muslim rule. They forget that, without Akbar’s policy of conciliation and inclusion of the native ruling classes in the state apparatus, there would be no Mughal Empire.

Also read: That Muslims enslaved Hindus for last 1000 yrs is historically unacceptable: Romila Thapar

Muslim antipathy to Akbar

In 1579, when Akbar issued the Mahzar (an official declaration often mistranslated as the “Infallibility Decree”) to style himself Imam-e-Adil (the just leader) and reaffirm his authority as final arbiter in religious disputes, the simmering discontent against his policy of relief to Hindus burst out in open. Led by his half-brother Mirza Hakim, the orthodox establishment rose in widespread revolt. Though it was eventually crushed, while it raged, it was a touch and go situation for Akbar.

There was such discontent against Akbar’s policy of religious liberality that his own court chronicler, Abdul Qadir Badauni (1540–1615), in his clandestinely written Muntakhab-ut-Tawarikh, castigated him in the severest terms and threw at him the worst religious calumny, accusing him of deviating from Islam.

Akbar in modern Muslim history

Historian Ishtiaq Husain Qureshi writes in The Muslim Community of the Indo-Pakistan Sub-Continent (610-1947): “Akbar had changed the nature of the polity profoundly. The Muslims were still the dominant group in the State, but it had ceased to be a Muslim State … [Akbar] was no more as dependent upon their support as earlier Sultans had been. Now Muslims were only one of the Communities in the empire which controlled the Councils and the armed might of the State … Akbar had so weakened Islam through his policies that it could not be restored to its dominant position in the affairs of the State.”

Criticising Akbar’s Rajput policy, Qureshi adds: “In the beginning they [the Mughals] saw with satisfaction and even pride that the Hindu had started “wielding the Sword of Islam”. They soon learnt that the Sword would not always be wielded in the interest of Islam.”

Akbar’s religious and Rajput policies have often been blamed for slowing the spread of Islam in India and diluting the distinct Muslim identity — the very axis around which Muslim politics and religion in India revolve.

The most influential Muslim thinkers of the 20th century — Maulana Abul Kalam Azad and poet Allama Iqbal — despite their differences, were unanimous in branding Akbar a heretic and apostate. Azad, in Tazkira (1919), applied the term Ilhaad (heresy/apostasy) to Akbar, and glorified Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi (1564–1624), the leading Naqshbandi sufi opponent of Akbar’s policies, reviving his forgotten legacy.

Historian Muzaffar Alam notes that Sirhindi’s rehabilitation by Azad as the counterpoint to Akbar “had a long historiographic afterlife… Sirhindi’s prominence in the South Asian Muslim imagination and history, however, remains almost unparalleled, comparable only to that of Shah Wali Allah of Delhi (d. 1762). In some circles, he is also considered the origin of the ideology of an independent homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent.”

Iqbal, spiritual acolyte of Sirhindi, in one of his poems, called him the guardian of the Muslim community in India — “wo Hind mein sarmaya-e Millat ka nigahban.” In another Persian poem, in which he sang paeans to Aurangzeb, he condemned Akbar: “Tukhm-e-Ilhaad ke Akbar parwarid” (The seed of heresy that Akbar nurtured).

Also read: How I unlearned my Islamophobia one step at a time

Different gazes at Akbar

Hindus and Muslims have always viewed Akbar differently. Hindus exalt him for the liberality with which he treated them in a polity where their persecution was summum bonum. He abolished jizya — a poll tax designed to humiliate non-Muslims (Quran 9:29). Historically, the burden of jizya led many to convert in the first wave of Islamic conquests — from Iran to Central Asia in the Sassanid territory, from Syria to Egypt in the Byzantine territory — and so too in India.

How demeaning jizya was can be seen in Ziauddin Barani’s account of cleric Qazi Mughisuddin advising Alauddin Khilji: “As soon as the revenue collector demands the sum due from him, [the Hindu] pays the same with meekness and humility, coupled with utmost respect, and free from reluctance, and he, should the collector chooses to spit into his mouth, opens the same without hesitation, so that the official may spit into it …” Centuries later, Aurangzeb echoed the same sentiments about jizya: “By this means idolatry will be suppressed, the Muhammadan religion and the true faith will be honoured, our proper duty will be performed, the finances of the state will be increased, and infidels will be disgraced.”

Akbar could not make Hindus equal citizens — far from it — but by removing religious disabilities like jizya and pilgrimage taxes, he alleviated their misery and, most importantly, restored their honour.

In the long history of Muslim rule, he was the first king to treat Hindus with dignity — and none after him ever surpassed him in this basic decency. His Rajput policy was not only statesmanly prudence but also a moral response to the rights of the sons of the soil.

And it didn’t stop here. To build an inclusive polity, he propounded the philosophy of Sulh-e Kul and, recognising the imperative of composite culture, founded the spiritual order Tauhid-e Ilahi (popularly called Din-e Ilahi).

So why do Muslims censure Akbar?

For precisely the same reasons that Hindus celebrate him.

As Abul Fazl wrote in Akbarnama, the root of Muslim discontent was that Akbar “received all classes of mankind with affection, and searched for evidence in religious matters from the sages of every religion and ascetics of all faiths.”

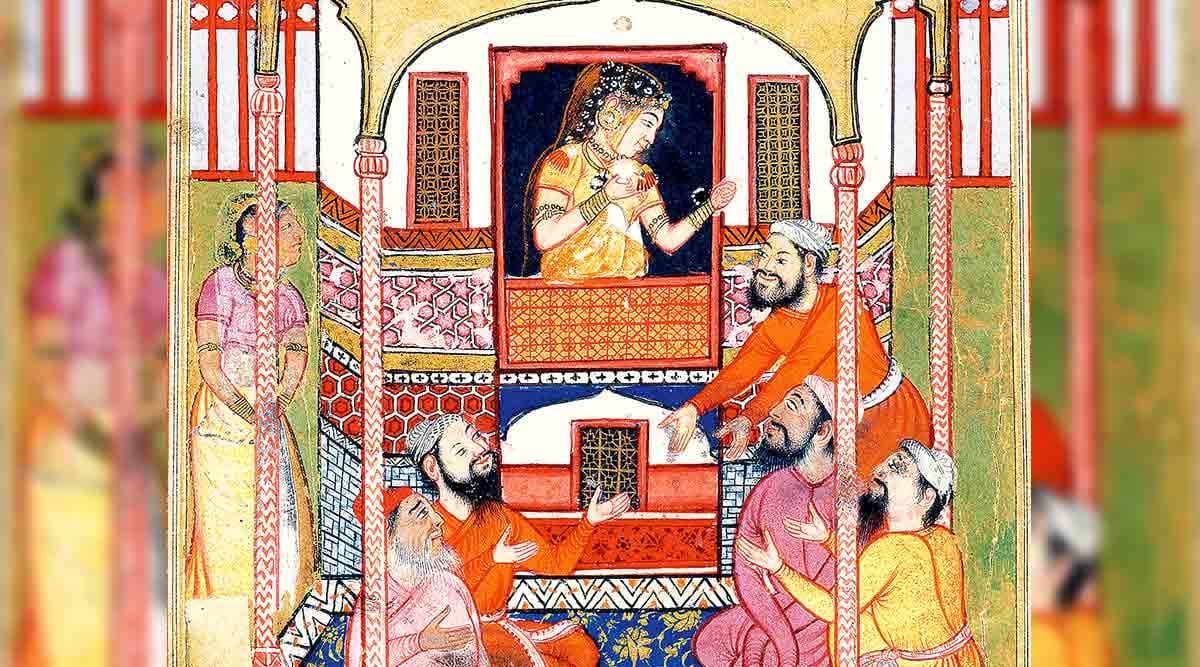

Muslims judged Akbar by the only measure they have — the yardstick of orthodox Islam. But he was far too big for that frame. His incorporation of Hindu practices in his spiritual exercises outraged them. His Ibadatkhana, where scholars of different religions and sects gathered to debate the issues of faith, placed Islam on an equal footing with “false” religions, something unacceptable to supremacist theology.

Sulh-e Kul — universal amity — was the radical departure from the theology of incessant Jihad until Islam triumphed and all other religions were extirpated. Akbar had the Ramayana, Mahabharata, and other Hindu texts translated into Persian. This reverence was interpreted as disrespect toward Islam.

It’s a travesty to say that Akbar’s stature is being diminished only now under the influence of the present dispensation. The bitter truth is: Muslims never held him in high regard. Had they truly honoured him, they would today hold aloft the ideals of Sulh-e Kul, which was the same as Sarva Dharma Sambhava, and conciliate Hindus as Akbar did by showing respect towards Hinduism and Indian culture.

Ibn Khaldun Bharati is a student of Islam, and looks at Islamic history from an Indian perspective. He tweets @IbnKhaldunIndic. Views are personal.

Editor’s note: We know the writer well and only allow pseudonyms when we do so.

(Edited by Prashant)