India’s purchase of Russian crude skyrocketed from $2 billion in 2021 to $53 billion in 2024, with New Delhi sourcing nearly 40 per cent of crude imports from Moscow. The discounted Russian oil offered meaningful benefits to India, an economy heavily dependent on imported oil.

Though purchasing price-capped Russian crude violated no international law, the US administration imposed punitive tariffs on India, doubling the already high tariff on imports from India to 50 per cent as of 27 Aug 2025, and hurting India’s goods exports to the US, worth $87 billion in 2024. Additionally, the European Union (EU), a key purchaser of Indian refined oil products, is also under some pressure to impose secondary sanctions on India. India exports $7 billion of refined products (WITS data) to the EU, and $77 billion when all goods are put together.

However, the calculus has recently shifted. On 22-23 October, the United States imposed new sanctions on Russian companies Rosneft and Lukoil, requiring non-US companies to wind down related transactions by 21 November. Indian refiners have stated they will comply.

This op-ed asks four questions. What are the economic consequences of India’s continued purchase of Russian crude? Who gains and who loses within India? What are the potential economic spillovers to India’s South Asian neighbours? And what are India’s options now?

Shrinking benefits

The benefits of buying Russian crude amounted to an annual benefit of about $10 billion for India. While the differential between the Ural and Brent crude after the war began in February 2022 climbed to as much as $25-30 per barrel, world oil prices softened significantly by mid-2024, and the differential had narrowed to $2.5 per barrel for FY 2024-25. A State Bank of India research report in August indicated that the continued purchases of discounted Russian crude in FY26 would increase India’s import bill by about $9 billion.

The operating margin in refinery exports to the EU is an indirect benefit. For example, Reliance’s operating margins as a share of revenue rose significantly in FY23 and FY24, going as high as 12.4 per cent in FY24, and remain higher in the quarter ending in September 2025 compared to any quarter in FY22. Moreover, it is debatable if the benefits of cheaper Russian crude have been passed on to retail consumers in India. For example, Indian retail diesel prices have been below the world average since 2021, and the wedge did not widen after 2022.

Also read: Saudi oil power is waning. What this means for its ties to the US

Rising costs—lost exports to the US

The costs of lost exports to the US alone could amount to $53 billion. This cost has two components. First, with the punitive tariffs in place, our Trade Sentinel-CSEP “Trump Tariff Simulator” shows Indian exports to the US declining by $31 billion, as trade is diverted away from India. Second, if India had not been sanctioned for buying Russian oil, its exports to the US could have increased by about $22 billion, gaining from trade diversion from countries with higher tariffs.

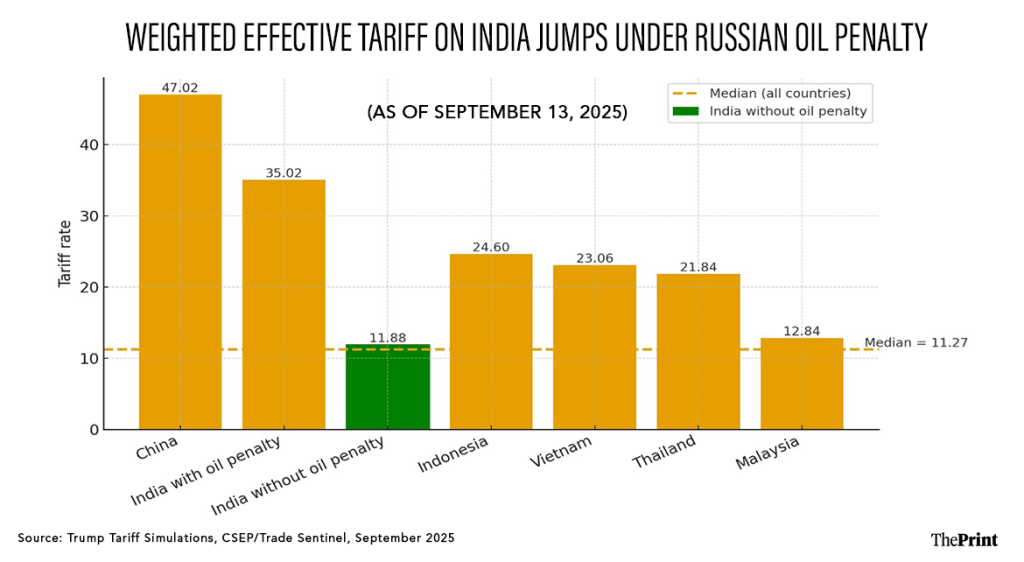

Chart 1 shows the relative effective tariff rate on India with and without the punitive oil tariffs. Without the oil penalty, India’s weighted effective tariff would have remained around 12 per cent, below many competitors. With the penalty, the tariff almost triples to 35 per cent, making it the second-highest tariff next only to China.

The arithmetic is stark. Even a high-end estimate of a $10 billion gain from Russian oil purchases is dwarfed by the $53 billion in lost exports to the US — a net cost of $43 billion, or $30 per capita for every Indian.

Perhaps more worrying than the aggregate loss are the distributional consequences of punitive tariffs. While the benefits of cheaper Russian crude mostly accrue to capital-intensive refiners (state and private), the lost exports affect a large segment of the working population, such as jewellery craftsmen, shrimp farmers, textile workers and others engaged in manufacturing. These are low-margin activities which are very sensitive to tariff differentials.

The employment cost, including direct and indirect jobs, of lost US exports could be as high as 8 million (based on 2020 employment norms for gross exports in OECD’s Trade in Employment database for India). This is comparable to the annual addition of young people (aged 15–29) into the labour force. India already had 23 million openly unemployed workers in 2022. A further influx of displaced workers carries social risk.

Also read: Govt shutdown, rate cut — US policy paralysis has created an opportunity for India

Regional spillovers

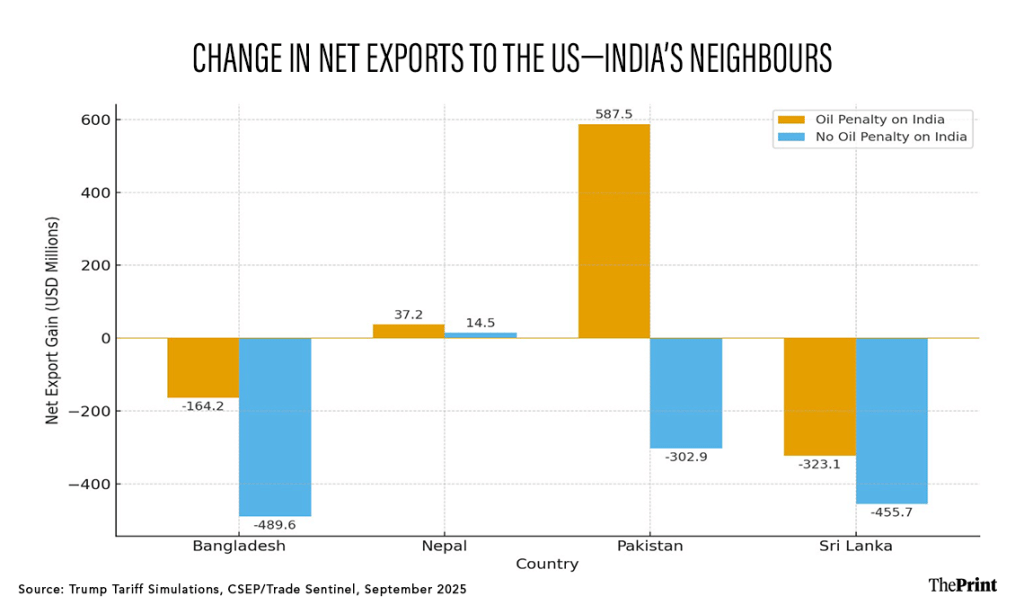

Punitive tariffs on India inevitably reverberate across South Asia. As trade is diverted away from India, its neighbours become the incidental beneficiaries of India’s loss. Without India’s oil penalty, its neighbours would all lose export share, except Nepal, which faces only a baseline reciprocal tariff of 10 per cent.

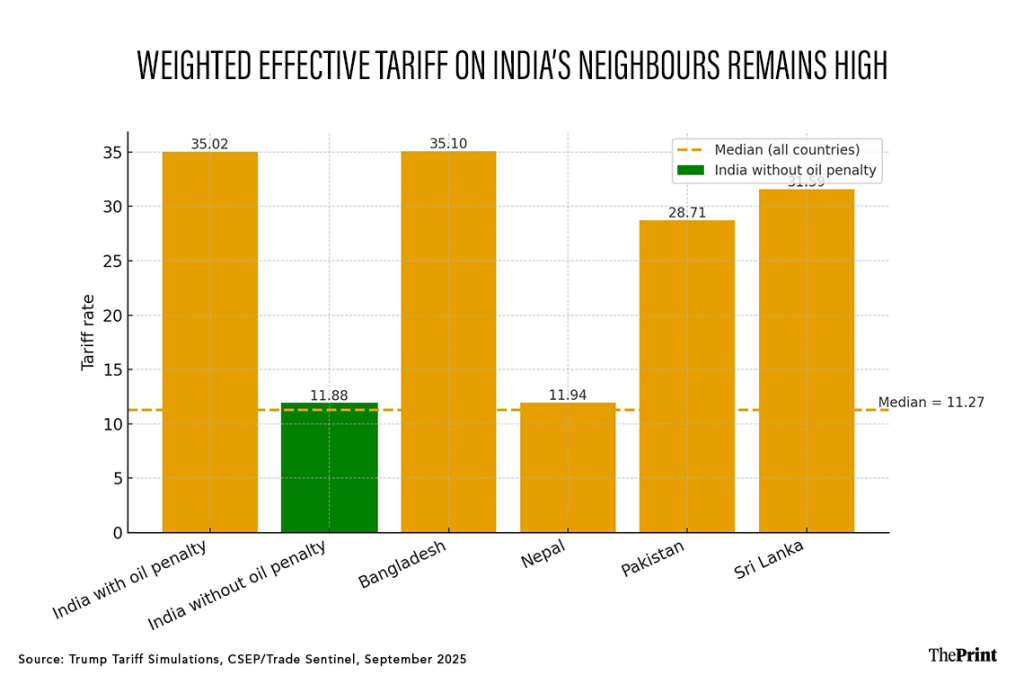

Given their export concentration in apparel, these economies already confront double-digit US tariffs (Chart 2). In the baseline scenario, India would gain $22 billion in exports, while the four neighbours together would lose $1.2 billion (Chart 3). Under the current oil-penalty regime, however, the pattern reverses—India’s exports fall, and the neighbours together register a modest $123 million aggregate gain. Bangladesh and Sri Lanka trim their earlier losses, Pakistan turns from loser to gainer, and Nepal improves its position slightly.

India’s options

The cost-benefit analysis of India’s Russian oil purchases is unambiguous, at least from a purely economic perspective. The $10 billion annual saving from discounted crude is outweighed by an estimated $53 billion in potential lost exports to the United States under the current tariff regime. These are projected, model-based losses — not yet fully realised — but they highlight the scale of India’s exposure. Even if this was not the intent of the policy, it has effectively meant a transfer of gains from millions of workers in labour-intensive sectors to a few large refiners.

With the new US sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil, Indian refiners have publicly stated that they will comply and are already weighing their options. Until now, India could not be seen as reducing Russian oil purchases under external pressure — it has its own strategic autonomy and priorities. But the new sanctions framework provides a legitimate, face-saving way to recalibrate. This creates a timely opportunity for an orderly and gradual exit from sanctioned barrels — a course that respects India’s legal obligations while safeguarding its autonomy. What is needed now is a basic understanding between India and the US on how much reduction in Russian oil purchases would be sufficient to lift the punitive tariffs. Already, there are some indications that differences are being ironed out.

At the same time, the tariffs provide one more signal and opportunity for South Asia’s value chains to deepen. For India, it provides yet another reason (among many others) to diversify production and investment across the region; for its neighbours, it is an invitation to proactively seek Indian investment and integrate into Indian and South Asian value chains.

Sanjay Kathuria is co-founder of the Trade Sentinel, a visiting senior fellow at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, visiting professor at Ashoka University, and nonresident senior fellow at the Institute of South Asian Studies. His X handle is @Sanjay_1818.

TG Srinivasan is co-founder of the Trade Sentinel, and visiting senior fellow at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress. His X handle is @tgsv. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)