Do laws designed to protect women from unsafe working conditions constrain the demand for their labour? This question sits at the centre of global debates about protective legislation in labour markets. Our recent research (Gupta et al. 2025) examines what happened when Indian states lifted long-standing bans that prevented women from working night shifts in factories. Our findings offer important lessons for policymakers seeking to expand female employment, particularly considering the significant labour reforms that have been recently initiated by many state governments.

The problem: When protection becomes restriction

For decades, Indian law prohibited women from working night shifts in manufacturing, ostensibly to protect them from unsafe working conditions and exploitation. The Factories Act of 1948 restricted women to working only between 6 AM and 7 PM in manufacturing units. Similar laws prohibited women from working night shifts in shops and other commercial establishments. While these laws were intended to safeguard women’s welfare, they inadvertently created barriers to female participation in the formal manufacturing sector.

This “paternalistic discrimination” (Buchmann et al. 2023) reflects a global pattern. At least 20 countries still prohibit women from working at night, while 45 countries ban women from sectors deemed “unsafe” by lawmakers (World Bank, 2024). These restrictions, however well-intentioned, assume women lack agency to make their own employment choices and that employers are unable to provide safe workplaces for all workers.

India’s experience is particularly important given its strikingly low female labour force participation rates and the potential for manufacturing to provide formal employment opportunities for women.

The reform: A natural experiment

In the early 2000s, a series of High Court judgements held that prohibitions against women working at night were unconstitutional because they deprived women of economic opportunities. Following these judgements, between 2014 and 2017, seven Indian states – Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Maharashtra, Punjab, and Uttar Pradesh – amended their regulations, either through legislative amendments to existing laws or through executive regulatory orders, to allow women to work night shifts in factories, though with certain conditions. State governments typically required employers to provide female-friendly amenities such as separate toilets, transportation facilities, mechanisms to prevent sexual harassment, and adequate rest periods between shifts.

These staggered reforms across states offer a unique opportunity to study the impacts of removing gender-discriminatory employment restrictions. We analyse data from over 290,000 registered manufacturing establishments from the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI), in the period from 2009 to 2018, to understand how lifting these bans affects female employment. We compare changes in firms before and after the reform and use ‘dynamic estimators’ that allow for the impact of the regulatory change to vary over time. We also use ‘synthetic control estimators’ that allow for the construction of a sample of appropriate counterfactual firms.

Key findings: Size matters

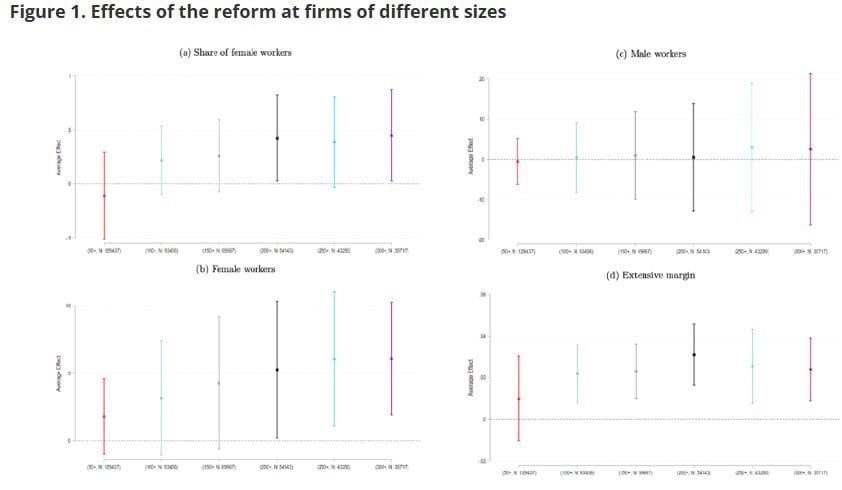

We find that removing night shift restrictions increased female employment – but the benefits were concentrated almost entirely among large firms with 250 or more employees (Figure 1).

In states that lifted the ban, there was a 3.5% increase in the share of female workers at large firms, a 13% increase in the number of female workers, and a 6.5% increase in the likelihood of a firm employing any female worker.

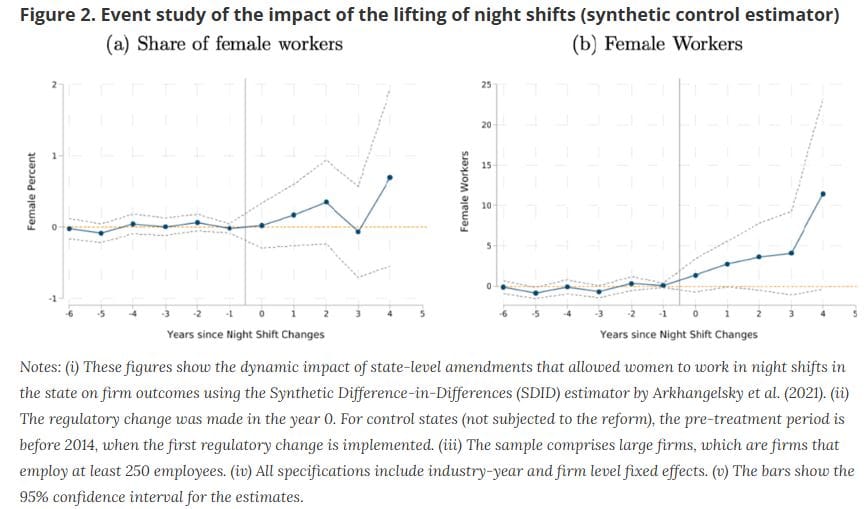

Our results are robust to the use of synthetic control estimators that construct a comparable counterfactual group to compare with treated (subjected to intervention) firms (Figure 2). There is no evidence of any trends prior to the reform that could be driving our results. After the reform is introduced, both the share of female workers and the number of female workers steadily increase at large firms. The gradual increase in the effects of the reform over time could reflect the time taken by firms to put in place the infrastructure required to employ women at night.

Crucially, the increase in female employment did not come at the expense of male workers. We do not find any decline in the number of male workers hired at large firms. In fact, we find an increase in the total workforce at large firms, although the estimated coefficient is not significantly different from 0. In short, large firms may have expanded their total workforce rather than substituting women for men, suggesting the reforms helped firms overcome labour constraints.

The concentration of benefits among large firms reflects the economics of compliance with the new regulations. While states lifted the outright ban, they simultaneously imposed requirements for female-friendly infrastructure and amenities. These compliance costs created a significant barrier for smaller firms.

Large firms are better positioned to absorb these fixed costs for several reasons: they can spread infrastructure investments across more workers, reducing per-worker costs, and they are more likely to already operate night shifts and employ some women (Chakraborty and Mahajan 2023).

Who responds most: Export-oriented and firms previously hiring females

We further examine which types of firms were most responsive to these regulatory changes. Firms that already employed women were much more likely to expand female hiring after the ban was lifted. This suggests that having existing female-friendly infrastructure and experience managing gender-diverse workforces positioned firms to take advantage of the new flexibility.

Export-oriented firms showed stronger responses than those focused on domestic markets. Companies operating in competitive global markets appear more willing to hire the best available workers regardless of gender, making them more responsive to the removal of hiring constraints. Firms in high-unemployment areas were also more likely to increase female hiring, likely because they could expand their workforce without driving up wages significantly.

Broader economic effects

Despite the increases in female employment, we find no significant changes in firm output or profits in the short term. This reflects the relatively small share of women in the overall manufacturing workforce. Even if firms want to hire women on night shifts to ease constraints in recruiting a sufficient number of productive workers, increases in female employment do not immediately translate to measurable productivity gains at the firm level. We also find a slight reduction in capital expenditure by firms: if labour was substituted for capital, then this could explain our finding that total output did not change. However, the extent of substitution is too small for us to find significant effects on profits, at least over the timeframe we are considering.

Wage rates for both women and men also remained largely unchanged. In some specifications, female wages even decreased slightly, suggesting that the regulatory changes may have also led to an increase in female labour supply. These results are also consistent with our previous result that the biggest increases in employment for female labour took place in labour markets which previous had relatively high levels of female unemployment.

Also read: Women’s employment in India up, yet 89 mn urban women remain out of work

Policy implications: Beyond simple deregulation

Our findings carry important lessons for policymakers seeking to expand female employment. In particular, while removing discriminatory laws does help increase female employment, the details of implementation matters. The concentration of benefits among large firms suggests that smaller firms need targeted support to develop female-friendly workplace infrastructure – whether through subsidies, shared facilities, or relaxing some of the compliance requirements where they may be unnecessarily onerous. Policymakers should also build on existing progress: since firms that already employ women are most likely to expand female hiring, policies encouraging even minimal initial female employment may have cascading effects.

The experience of these seven Indian states offers a glimpse of the economic costs of gender discrimination – even discrimination that is arguably well-meaning in intention. Our research provides an example of one such discriminatory legislation that constrains firms from hiring females who are able and willing to take on productive work and suggests that removing such distortionary regulation could reduce the economic gap between less developed and more developed countries.

Bhanu Gupta is an Assistant Professor of Economics at Ashoka University. Kanika Mahajan is an Associate Professor at Ashoka University. Anisha Sharma is an Associate Professor of Economics at Ashoka University. Daksh Walia is a Predoctoral Fellow in Economics at the University of Oxford. Views are personal.

This article was originally published on Ideas for India website.

I wonder if any of the female authors spent a single night shift in a smaller firm. It is easier to preach about smaller firms making amenities but what about when those females step outside to go back to their homes. Does our government provide adequate security to them The answer is no.

Also these researchers play with the graphs. The slope of Share of Female workers graphs is steeped up to show a great change of 0.5%.

By making the women do night shifts at firms , how will their families cope up. Who will love the kids at home. The whole article seems to be biased with Leftist agenda.