The lives of asset poor in India’s major states, as shown in an earlier article, have improved between 2005-06 and 2015-16 in terms of owning common durables. Asset poor are defined as the bottom 20 per cent of a state’s population in terms of durable asset ownership.

It is important to note that asset poor in one state can be asset rich in another state since there are wide regional variations in the level and changes of asset ownership. For example, an asset-rich person in 2015-16 who is almost in the top 10 percentile in Bihar has the equivalent level of durable asset ownership of an asset-poor person in the bottom 20 percentile in Punjab.

In this article, we look at the state-wise differences in the quality of housing and access to government provision of basic services among the asset poor. Access to good quality basic social services — for example, clean, regular and easy access to water and sanitation, electricity, banking — is not only essential for improving the well-being of the poor, but it also enables them to participate in the economy, raising their income levels and hence the ability to buy durable assets.

Moreover, basic services such as regular and stable supply of electricity and water act as complementary services without which durables such as a refrigerator or a washing machine would not provide utility. Additionally, the size of homes itself may impact the decision to purchase a durable asset that requires space.

Using data from two rounds of the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) in 2005-06 and 2015-16, we construct an index of basic services where households are differentiated based on access and quality of these services. For example, if a household has water supply piped into its dwelling or via a public tap or a tube well, whether it has access to clean cooking fuel, whether it has an improved sanitation facility, and so on.

Also read: What owning a bike in Punjab, Tamil Nadu and Bihar tells us about India’s asset poverty

Poor delivery compliments quality of services

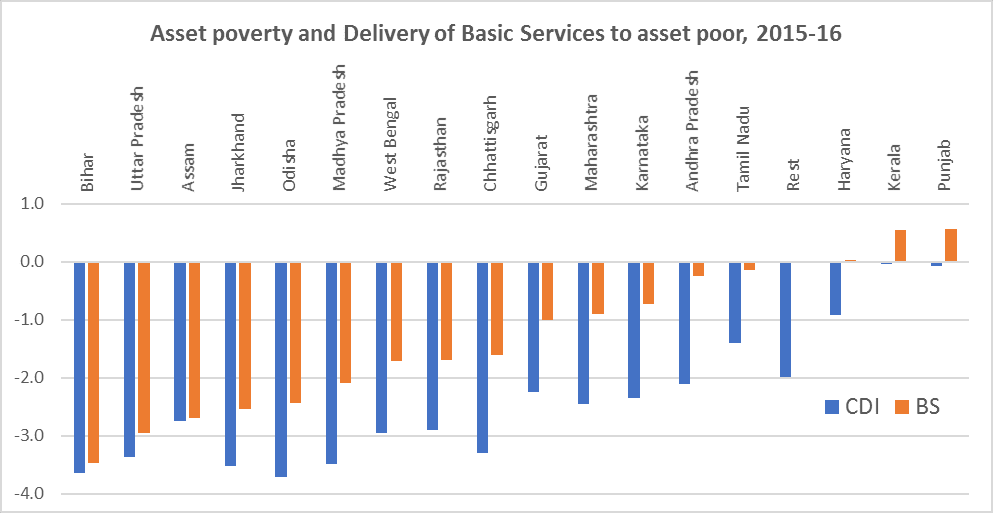

We find that asset poor of Kerala and Punjab were receiving the highest level of basic services among asset poor of major Indian states in 2015-16 (Figure 1). Haryana, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh (among India’s prosperous states), and West Bengal and Rajasthan (among the laggard states), have remarkably improved the delivery of basic services to their poorest 20 per cent population between 2005-06 and 2015-16. As a result of this superior performance, West Bengal and Rajasthan have pulled significantly away from being the worst-performing states in terms of the provision of basic services to their asset poor.

Figure 1

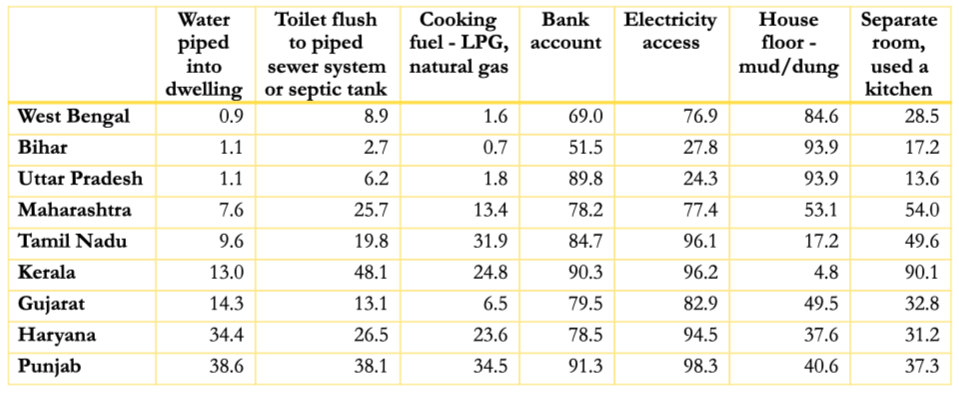

Bihar remained the worst performer in terms of asset poverty as well the reach of basic services to asset poor in 2015-16. Replacing Odisha from 2005-06, Uttar Pradesh was the second-worst state in 2015-16 as far as asset poor’s access to basic services was concerned (Table 1). In 2015-16, less than 2 per cent of asset poor in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh had access to piped water in their homes while the same was true for nearly 40 per cent in Punjab and Haryana. Over 30 per cent of asset poor used LPG as their cooking fuel in Tamil Nadu, whereas less than 2 per cent had the same access in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in 2015-16.

Table 1: Delivery of public services among bottom 20% population in each state by the durable asset score, 2015-16

In terms of housing quality, over 90 per cent of asset poor in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh had had mud or cow dung flooring in their houses in 2015-16. In contrast, less than 5 per cent and 20 per cent of Kerala’s and Tamil Nadu’s asset poor, respectively, had homes with similar floor material in the same year. At one extreme, less than 2 in 10 homes of asset poor in Bihar had a separate kitchen compared to over 9 in 10 homes of Kerala’s asset poor. Among the prosperous states, the smaller size homes among asset poor are noticeable in some of the states. While over 70 per cent of Maharashtra, Karnataka and Gujarat’s asset poor have only one room, which is used for sleeping, only about 20 per cent of Kerala’s asset poor are in the same situation.

Overall, asset poverty and poor quality of delivery of basic services, as well as the quality of housing, seem to largely go hand-in-hand. Given the complementarity among these three, while raising income levels of the asset poor is a necessary condition to raise their affordability levels to buy durables, it would not be sufficient. Higher-income levels need to be supported by an improvement in the quality of basic services and homes. When NFHS-5 unit level data for 2019-20 becomes available, it would be interesting to repeat this exercise since there has been a push for an improvement in the delivery of basic services in recent years.

Vidya Mahambare is Professor of Economics, Great Lakes Institute of Management, Chennai. Sowmya Dhanaraj is Assistant Professor of Economics, Madras School of Economics. Views are personal.

This is the second article in a series on asset poverty in India. Read the first article here.

(Edited by Prashant Dixit)