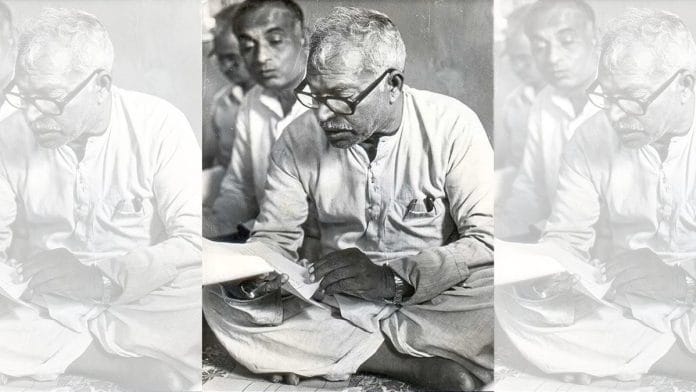

Karpoori Thakur, the Bharat Ratna winner, was a socialist and an extraordinary mass leader. The Jan Nayak rose from a ‘low caste’ Nai background to become chief minister of the influential state of Bihar. A member of Bihar’s legislative assembly from 1952 to 1988, barring a stint in Parliament in 1977, he served two terms as the state’s chief minister – from 1970 to 1971 and then again from 1977 to 1979.

Thakur’s search for socialism – not that myopic mixture of Marxism-Leninism-Stalinism –took him to Israel, which was socialist but not a communist country. According to Israeli archives, he was impressed by the country’s socialist movement and labour organisations in the 1950s. In those years, India did not have diplomatic relations with the country. It recognised Israel in 1950, establishing full diplomatic relations only in 1992. Yet, Thakur spent two months in the country – from June to August 1959 – to study its cooperative organisations and different agricultural settlements. Inspired by the socialist Zionist movement and the Kibbutz – a traditionally agrarian voluntary collective community – his visit was part of the decade-long engagement with Israel by leaders like Ram Manohar Lohia, Ashok Mehta and Jayaprakash Narayan.

During the 1950s and ’60s, many Indian leaders from the Congress and other parties actively engaged with Israeli political leaders and community figures. First, by visiting Israel to experience and study the Kibbutz system and democratic-socialist Zionism, as well as maintaining long correspondence with leaders like the former Israel PM David Ben-Gurion. Second, by facilitating and inspiring hundreds of others from Indian socialist camps, grassroots movements, and trade-labour unions to visit Israel. And third, by advocating for full diplomatic relations with the country.

Karpoori Thakur’s Israel engagement

The delegation headed by Thakur had three other key members: Jagdish Singh, joint secretary of the state branch of Praja Socialist Party in Bihar; Dawarko Sundrani, from Vinoba Bhave’s Samanwaya Ashram, and Ramesh Jha, politician and member of the Bihar legislative assembly. In their two months of stay, Thakur and his delegation lived on several Kibbutzim from Kfar Giladi, up in the north, to Sde Boker, south of Israel, where each day they worked for four hours with other Kibbutz members. They met with intellectuals and the public at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Technion (technical) university of Haifa, the Weizmann Institute of Rehovot, the Workers College of Tel Aviv, and the Bet Berl Institute. From Israeli archives, I have found a detailed report of their field trips to their socialist groups in India, where they observed: “The Kibbutz is an organic community. It aims at not only social and economic equality but the creation of a synthetic personality as well”.

Thakur was moved by the non-dictatorial socialism practised in Israel. As a socialist and democratic person, he asked for more contact between Indian and Israeli socialist movements. He was critical of India’s diplomatic distance from Israel. He did not consider Zionism as a settler-colonial project but a legitimate Jewish national movement with unique socialist ethos and practices that he observed all over Israel. The Israel-Palestine conflict was not resolved then, Israel was not occupying the West Bank and Gaza either (Jordan and Egypt had control over them).

Thakur’s observations resonate with the ongoing debates about socialism in India, particularly regarding its implications for economic policies and social justice. The lessons learned from his experiences in Israel could provide valuable insights into the future of socialist movements in India.

In his summary of the long trip, which he wrote from the Kibbutz of Kfar Giladi, he stated: “Kibbutzim in Israel have proved beyond all doubt that bread and freedom can go together. The percepts and practices of the dictators [reference to Joseph Stalin in the Soviet Union and Mao Zedong in China] have been totally falsified. [The] living experience here has conclusively shown that to sacrifice freedom for bread and vice-versa is not at all necessary. We in our country also cherish the same goal(s) of democracy and socialism. For us, both are equally valuable.”

Also read: Israel’s first PM called Nehru a ‘great man’. Asked him to moderate peace in the region

Nehru encouraged Karpoori Thakur

Some of our early socialist leaders were Gandhians who detested the Marxist-Leninist and Communist models because they were undemocratic and violent. Israel, after its establishment in 1948, did not join the Soviet Union or the American camp and adopted a policy of non-identification. Much like Indian socialist leaders, Israeli leaders chose democracy and socialism and not communism. “Our relations with Israel since 1948 have been friendliest. Our great leaders like Acharya (Professor) Narendra, Acharya JB Kripalani, Shri Ashok Mehta, Shri Jai Prakash Narain and [a] host of other socialist and Bhoodan workers have visited this country in the past and have been greatly impressed with the progress and way of life and standard of living of the Kibbutzim,” wrote Thakur in his trip notes, which can be found in Israeli archives.

New Delhi’s diplomatic distance from Israel did not prevent them from engaging with the latter’s labour movement. Jawaharlal Nehru was aware of it and allowed them to travel to Israel and invite Israeli labour leaders to various conferences and collaborations with India. On 19 April 1960, the Minister of Community Development and Co-operation, Surendra Kumar Dey, presented the findings of Thakur’s delegation to Israel in the Parliament, saying that the “cooperative movement in Israel has grown to its present stature because of a band of selfless workers with high idealism”. Reading the notes of the parliamentary discussion over the findings of the delegation led by Thakur, one can assume that the Indian government sent it to Israel.

India did not have diplomatic ties with Israel from 1950 until 1992, and many may consider this period as blank or as one marked by a boycott of Israel. But as the example of Karpoori Thakur shows, it clearly wasn’t the case. In his quest for learning and building a socialist and democratic world, he found Jews, Zionism, and Israel as partners.

Dr Khinvraj Jangid writes from Tel Aviv. He is Associate Professor and Director, Centre for Israel Studies, Jindal School of International Affairs, OP Jindal Global University, Sonipat. He is visiting faculty at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)