It is not surprising that the choice of a new religious head of about seven million Tibetans should give sleepless nights to an economic and military colossus. China is of late worried about the succession plans of the 14th Dalai Lama, who took refuge in India in 1959. It has every reason to be worried, if not feel guilty, about what it did to Tibet, its culture, and above all, the political and religious leader of its people.

The Tibetan people’s resistance to Chinese occupation began as early as 1950, when Mao Zedong’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) marched into the land of the ‘uncultured’. The 1959 Lhasa uprising – led by Khampa guerrillas who called themselves ten-sung or defenders of the faith – was aimed at protecting Tibet, its religion, and the Dalai Lama, who had just completed his formal studies in philosophy and religion at the age of 23, passing the final examination at Lhasa’s Jokhang Temple during the annual Monlam Prayer Festival.

Notably, the Dalai lama had visited India three years prior, in 1956, to attend Buddha Jayanti celebrations and see if asylum could be sought in the country. According to some biographers, his request was not met with much enthusiasm by then-Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. Nehru is reported to have told the Dalai Lama that “India cannot support you…You must go back to your country and try to work with the Chinese on the basis of the Seventeen-Point Agreement.”

However, when the PLA brutally killed thousands of protesters and attempted to arrest the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, he fled to India with the help of his trusted followers and some Western diplomats. He crossed the border into India at Khenzimane, on the bank of the Namjiang Chu River in Arunachal Pradesh’s Tawang sector, on 31 March 1959.

Since then, 10 March – the day of the 1959 uprising in Lhasa – has been widely observed by Tibetan groups as “Free Tibet” Day, symbolising the hope that some day, their land will be free from Chinese occupation.

Why China eyed Tibet

Mao invaded Tibet in a bid to annexe border areas and consolidate his position as the ruler of all the lands that he surveyed. Tibet also offered enormous natural resources, rivers, and, more importantly, proximity to several countries south of China.

In 1949, Mao ordered the PLA to invade Xinjiang and integrate the ‘border country’ into the People’s Republic of China. This was done to prevent the Nationalist Forces, primarily the Kuomintang (KMT) led by Chiang Kai-shek, from using it as a base. The rich oil reserve of this area was another reason, as would be substantiated by future research. The best strategic advantage of annexing Xinjiang was that it afforded China borders with eight countries: Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Mongolia, and Russia. The following year, Mao proceeded to occupy Tibet, which gave China new borders with India, Nepal, Myanmar (then Burma), and Bhutan.

Also read:

India must revisit Tibet

It’s strategically important for India to revisit the Tibet issue given the present geopolitical dynamics. China’s not-so-peaceful rise, its proximity and support to a terrorist state like Pakistan, and its overall strategy of encircling India and creating a hostile neighbourhood make it crucial for New Delhi to recalibrate its Tibet policy and pay renewed attention to the One China policy. As for Beijing, it appears to still follow Mao’s strategic vision—which considered Tibet as China’s palm and the Himalayan regions of Ladakh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and Arunachal Pradesh as its five fingers.

There is an argument in the public domain that India has always accepted Tibet as an integral part of China through centuries-old treaties and trade agreements such as the one signed in 2003.

Out of the nine MoUs signed between India and China in June 2003, during the National Democratic Alliance government led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee, only one MoU pertains to border trade between India and China.

According to the Ministry of External Affairs, in pursuance of the December 1991 MoU on the resumption of border trade and the July 1992 Protocol on Entry & Exit Procedures for Border Trade, India agreed to designate Sikkim’s Changgu as the venue for a border trade market. “The Chinese side agrees to designate Renqinggang of the Tibet Autonomous Region as the venue for border trade market,” the 2003 MEA release read.

As a consequence of this border trade agreement, China agreed that Sikkim was a part of India, and India agreed that Tibet was a part of China. However, considering the border disruptions amid Covid-19 and the unprovoked attacks by the PLA on Indian patrol groups, the border trade agreement needs to be reanalysed.

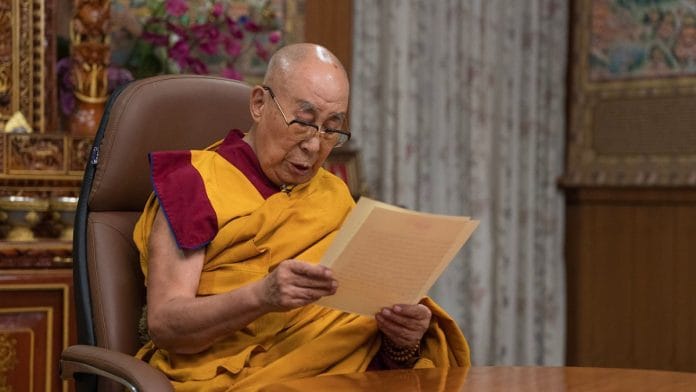

Beijing has no legal or moral right or authority over the religious affairs of Tibet, the Dalai Lama, or his successor. In March 2011, the Dalai Lama relinquished his political authority as the head of the Tibetan government-in-exile, transferring it to a democratically elected leader. As of now, the Dalai lama is the spiritual head of the Tibetan Buddhist order.

The political institution that he once headed has a new leader. And it can and should be recognised as a government in exile by India and other countries that truly value freedom of religion and democracy. The conflict, after all, is no longer between Beijing and the Dalai Lama. It’s an autocratic and brutal hegemon versus a spiritual leader and his religious right.

Seshadri Chari is the former editor of ‘Organiser’. He tweets @seshadrichari. Views are personal.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)

My view is that India and China have a lot of issues to resolve through a substantive peaceful dialogue. Let this not be added to the pile. The whole world accepts Tibet to be an integral part of China. For China, a sovereignty issue, which all countries are exceedingly sensitive about.