Seven years is a long gestation period for a 75-minute documentary film. But even that’s not enough to capture the decades-long pioneering work of India’s “Turtle Man,” the late Satish Bhaskar.

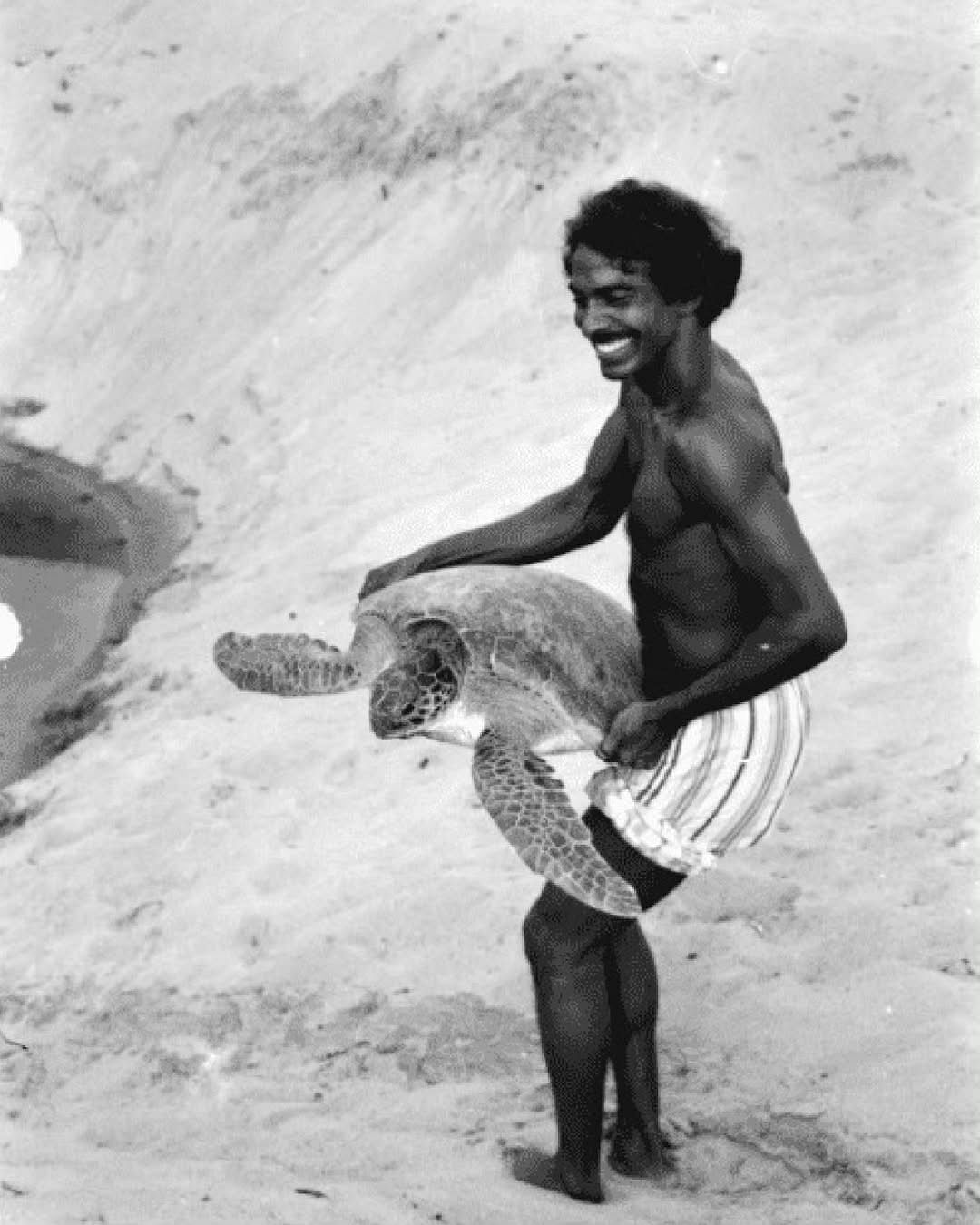

In the 1970s, the shy and retiring Bhaskar achieved something remarkable. He walked most of India’s 7,516 km coastline to discover and mark sea turtle habitats. Armed with little more than scant information, a small transistor, limited institutional support, and no Plan B, Bhaskar conducted primary research that set the baseline for all turtle conservation efforts in India. And he did it all by himself, like a Homeric hero.

Bhaskar is the subject of the affecting new documentary, Turtle Walker, by Taira Malaney. Produced by Emaho Films, Malaney’s Goa-based studio, the film was recently screened at DOC NYC and has already received the Grand Teton Award—the highest honour at the Jackson Wild Media Awards. It’s difficult to believe that this rousing ode to Bhaskar’s spirit of adventure is Malaney’s directorial debut. But it’s easy to see why well-known production companies like Tiger Baby (owned by film directors Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti) and Oscar-nominated HHMI Tangled Bank Studios chose to back it.

Solitude, letters in bottles

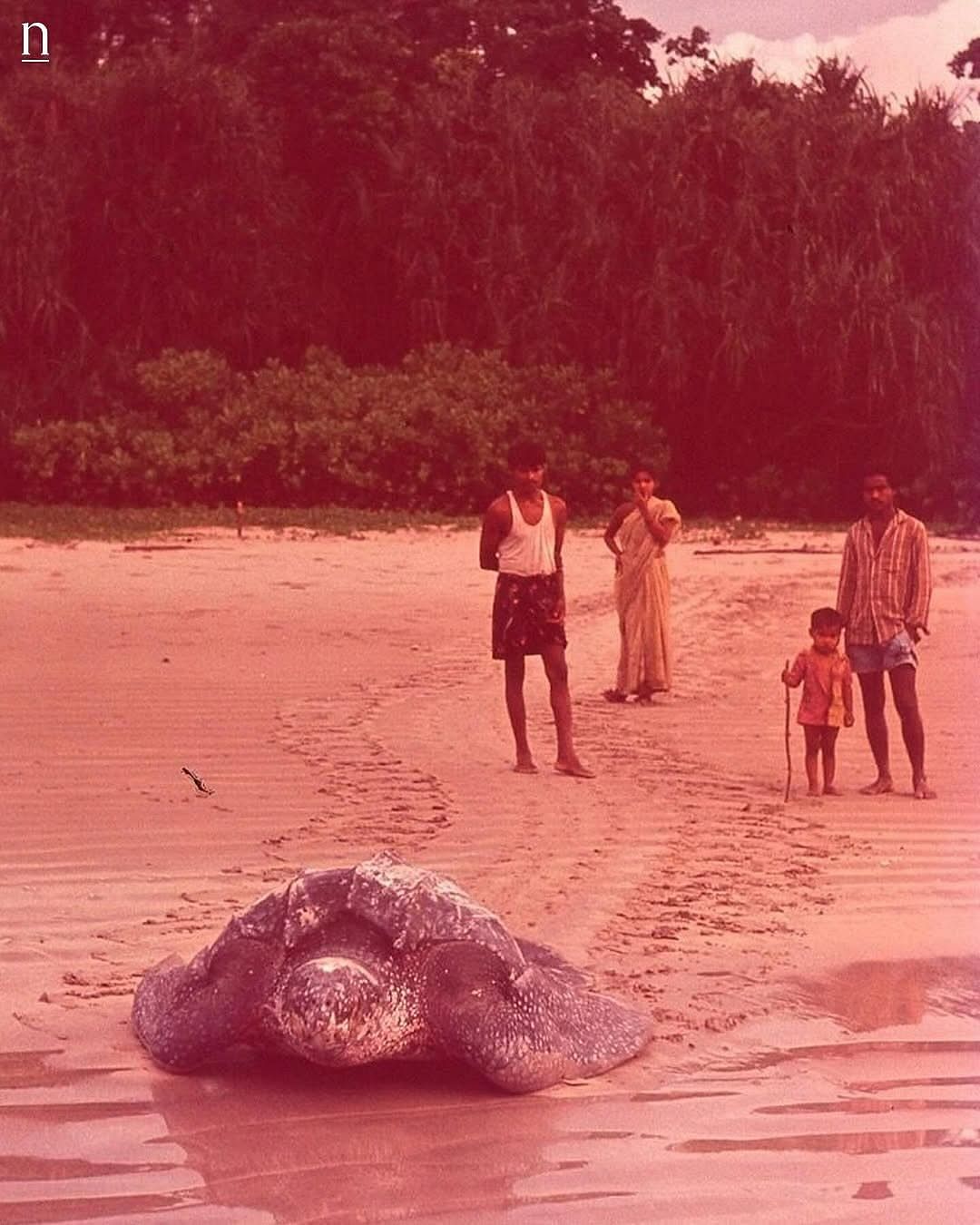

Far from being a stodgy “nature film” with a hectoring tone, Turtle Walker is more than just a chronicle of Satish Bhaskar’s solitary odyssey along India’s coastline. It’s a meditation on devotion and the sense of wonder the natural world can inspire—the kind that drove Bhaskar to spend months alone on uninhabited islands, mapping the ancient chemistry of enigmatic marine creatures.

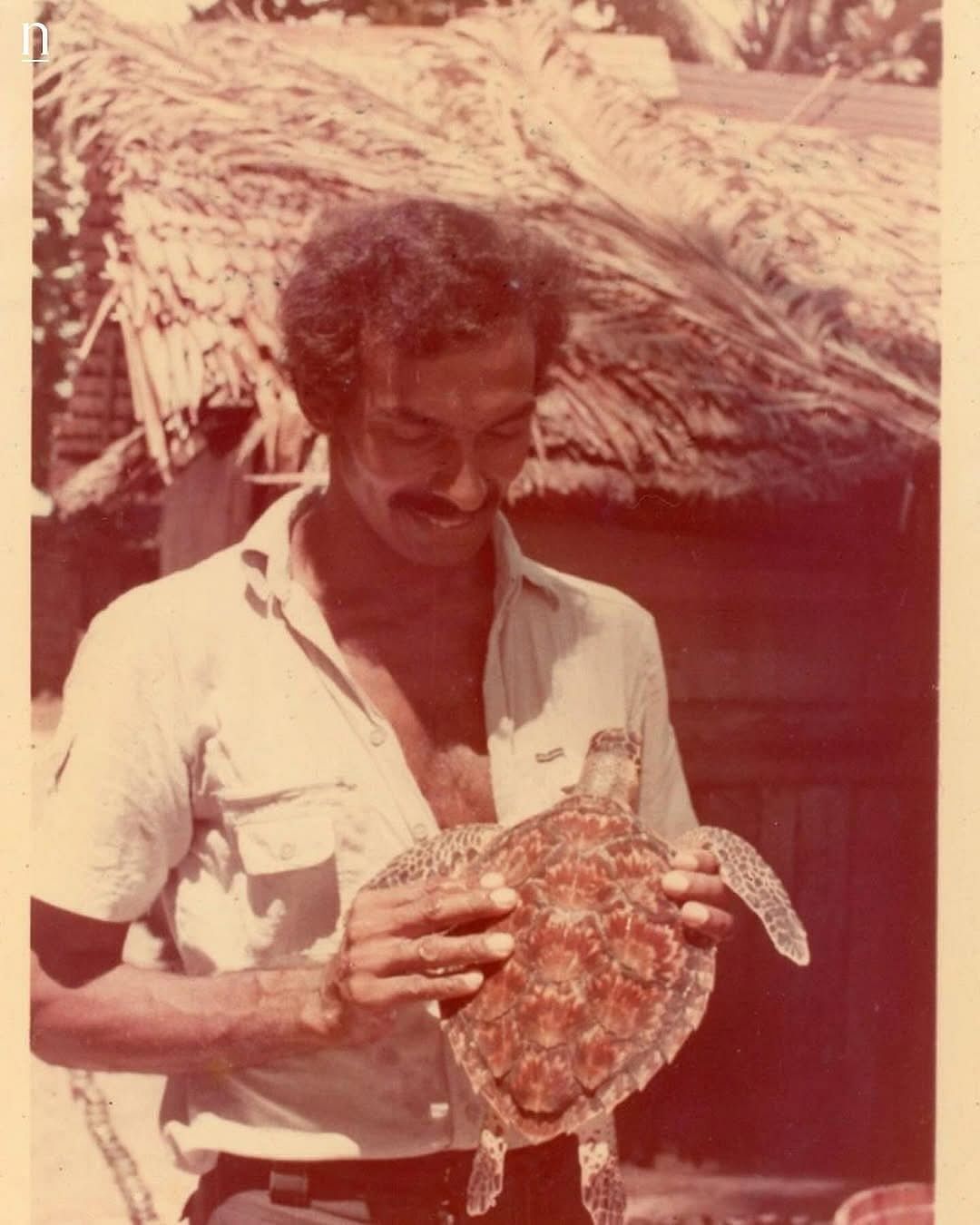

Yet, as Bhaskar says in the documentary, recalling a sea turtle laying eggs beside his ramshackle hut in Suhelipara (a remote Lakshadweep island), “I never felt alone.” That’s Bhaskar likely papering over the emotional lows of his incredible journey. Bhaskar sometimes spent five months at a stretch with not a soul to talk to, resorting to writing letters in glass bottles to his cheerful wife Brenda—one even made its way to her via Sri Lanka.

Most of Bhaskar’s time, however, was devoted to the single-minded pursuit of understanding sea turtles. Over his career, he authored nearly 50 reports and papers. His almost inconceivable journey took him to Kerala, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Orissa, the Andaman & Nicobar Islands, and West Papua, Indonesia. In Suheli, Bhaskar realised there was no way for him to keep returning to the island during the monsoon, which is when sea turtles nest—so he decided to “maroon” himself for the entire season.

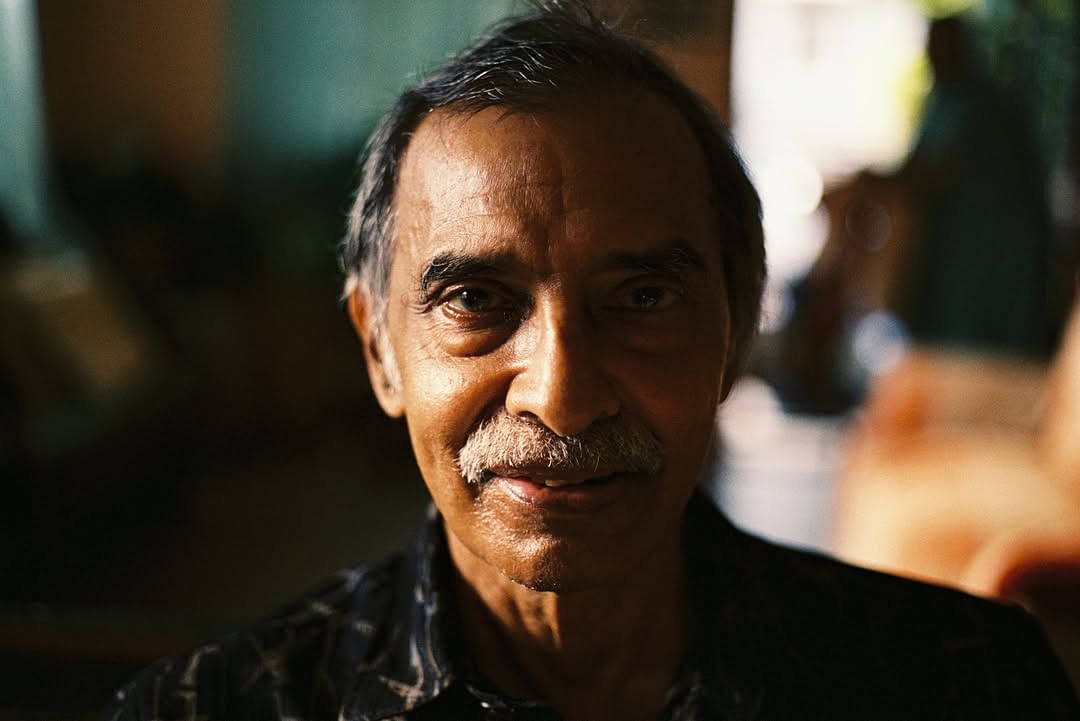

Perhaps his most satisfying time was spent on South Reef Island in North Andaman, where he studied the nesting biology of hawksbills, the most solitary of sea turtles. Sadly, the island was devastated by the 2004 tsunami. According to Malaney, Bhaskar longed to return to South Reef, prompting the crew to accompany him there during production. Predictably, the island was too hazardous to approach by boat.

“We weren’t prepared for him to just dive in,” Malaney told me. Despite the treacherous conditions, Bhaskar, then 73 and battling trigeminal neuralgia (a painful nerve condition), donned his fins and entered the water that had defined his life’s work. The crew scrambled to keep up—a testament to his indomitable spirit.

That unscripted moment captures what drew Malaney to Bhaskar’s story—witnessing how a lifetime of fealty to nature leaves indelible marks.

A natural connection

For Malaney, the journey to Turtle Walker began far from the shores of South Reef. Growing up in Mumbai with parents who ran a camping group in Maharashtra, she developed an early intimacy with the natural world.

“I’ve always been very comfortable in nature,” she reflects. “It surprised me when I saw that in some pockets of urban India, there is a fear of nature.”

While working with Reef Watch, a marine conservation NGO in the Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Malaney uncovered a paradox: local children living by the ocean had never swum in it. This realisation became the backbone of her work, creating bridges between people and wild spaces beyond their comfort zones. “That’s when I discovered the transformative power of visual storytelling,” she said.

Turtle Walker began as a modest addition to Malaney’s conservation film series, following A Living Legacy (about Coorg’s SAI Sanctuary) and The Call of Pashmina (about Ladakh’s changpa tribe). But the project soon evolved into something far more ambitious. The catalyst was an article by herpetologist Rom Whitaker, full of “old jungle sayings” about Bhaskar. These stories led Malaney to him, who lived just an hour away in Goa, beginning a much longer journey.

With no archival footage available, Malaney relied on creative reconstructions of Bhaskar’s travels. The decision to dramatise came after studying films like Jago: A Life Underwater (2015), whose co-director James Reed (also the co-director of Oscar-winning My Octopus Teacher) serves as Turtle Walker’s executive producer. Artist Rohan Joglekar, who embodied the young Bhaskar, emerged from the production’s careful attention to authenticity. “Krish Makhija, our cinematographer, comes from a fiction background and understood how to frame these moments and work with ‘characters’,” Malaney explained.

Beyond preserving Bhaskar’s legacy, Turtle Walker has turned into a living document of ongoing conservation. For five years, Malaney and her team have led impact campaigns that will hopefully transform viewer engagement into tangible action. They collaborate with Marine Mammal and Megafauna Stranding Network, a rescue and response programme in Goa, which mirrors Bhaskar’s spirit of hands-on conservation. The programme has responded to over 440 strandings of dolphins, whales, turtles, and sharks, working with local lifeguards who are trained as first responders—a contemporary echo of Bhaskar’s solitary vigils.

The network’s work has also uncovered new conservation challenges that Bhaskar could not have foreseen. An antibiotics resilience study highlights how modern effluents are creating resistant strains in marine life, adding complexity to conservation efforts.

Yet, within these challenges lies hope. Every rescue represents another thread in the expanding web of marine conservation that Bhaskar began weaving decades ago. Like Bhaskar’s bottle-letter crossing oceans to reach his wife, Turtle Walker carries its own message—that the dedication of one individual can ripple outward, touching shores they might never have imagined reaching.

Karanjeet Kaur is a journalist, former editor of Arré, and a partner at TWO Design. She tweets @Kaju_Katri. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)