If India sustains even a modest version of its current economic trajectory, it will be a 1.6-billion, half-urban nation, richer in aggregate, and digitally connected by 2037. And yet home to millions who remain one illness, drought, or job loss away from hunger.

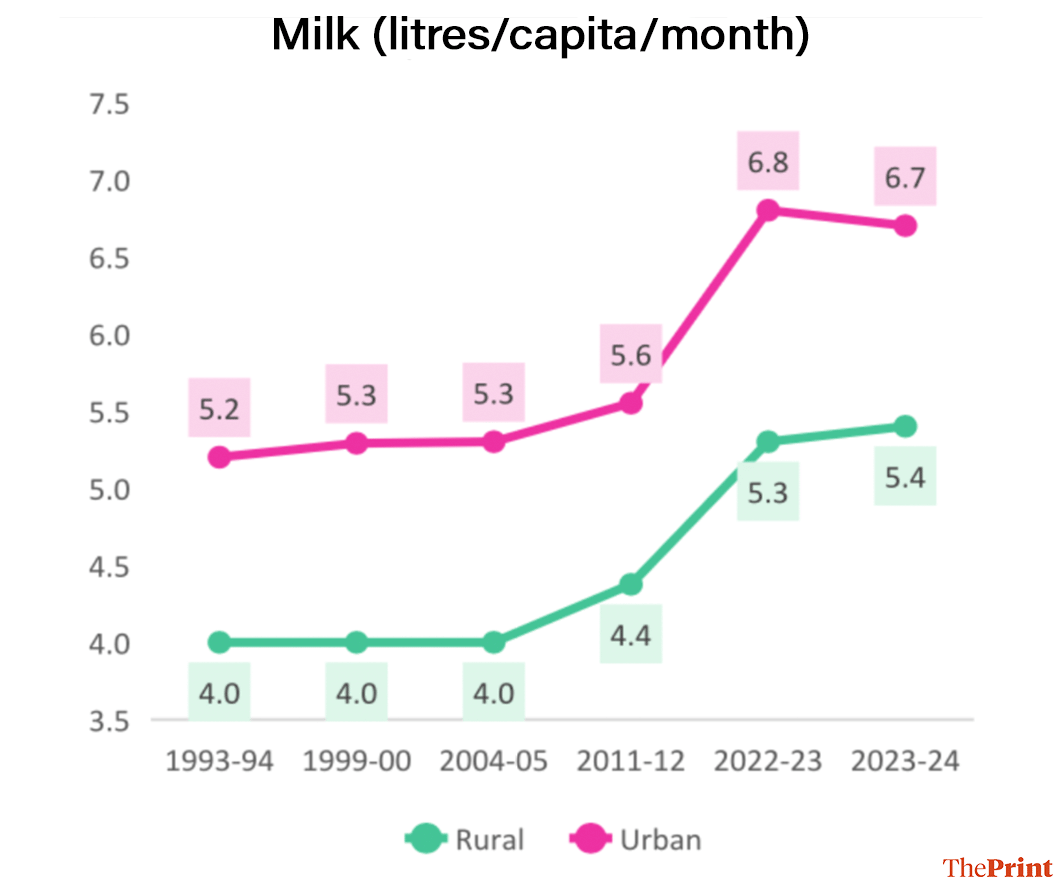

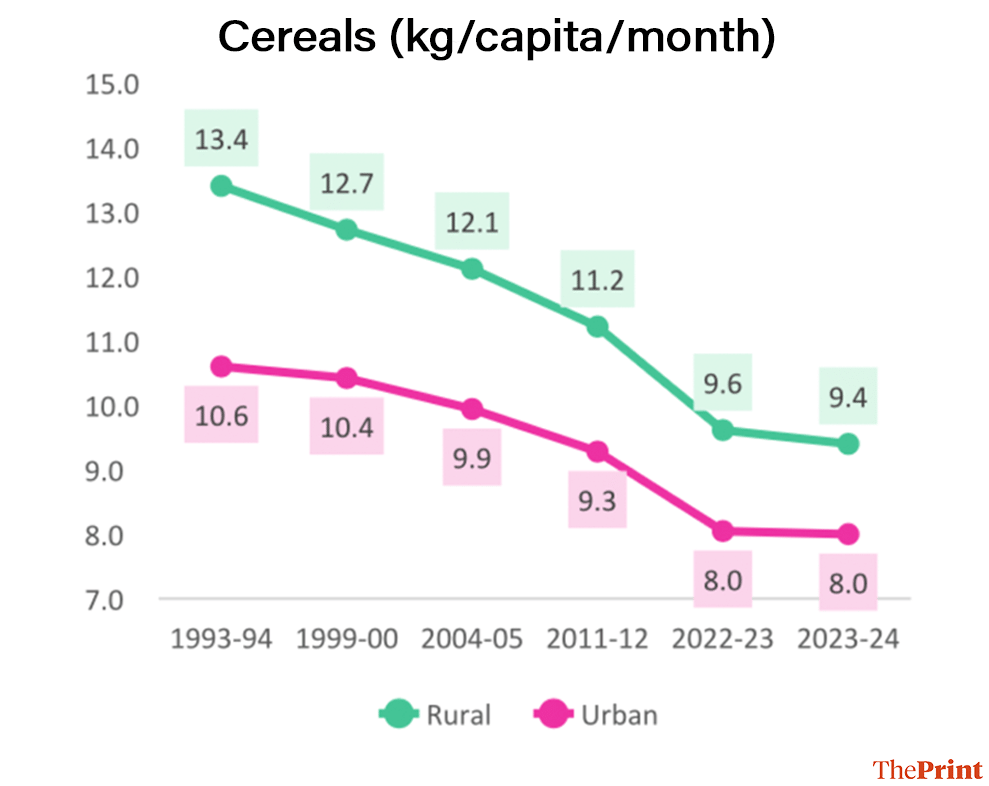

Almost every adult will possess an Aadhaar card, a bank account, and a UPI-ready phone, turning the delivery of welfare transfers into an act no more complex than sending a text message. Their ‘thali’ (plates) will be unrecognisable from that of the 1960s: more dairy, vegetables, fruits, eggs, and less dependence on cereals. Their fundamental concern will most likely shift from “will we eat?” to “can we afford nutritious food every day?”

This is an unavoidable question: Can the Public Distribution System (PDS) continue unchanged in an era where the demand is likely to be for nutrition, convenience, and choice? No.

Brief history of PDS

India’s PDS emerged in 1942 in response to the Bengal famine and the market failures that followed. For decades, it functioned as a largely universal safety net before a pivotal shift in 1997 with the introduction of the Targeted PDS, which provided differentiated support through the Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) for the poorest households, as well as those below and above the poverty line. This structure was recast in 2013, when the National Food Security Act (NFSA) converted subsidised grain into a legal entitlement for up to 75 per cent of rural and 50 per cent of urban populations, reaching 813 million people today.

Here are the reasons why the old design no longer fits:

- Leakages persist, though at much lower levels than before. Recent estimates suggest that 22 to 28 per cent of PDS grain leaked in 2022-23—around 18 to 22 million metric tonnes (MMTs) of rice and wheat—down from 42 to 46 percent in 2011-12. Aadhaar integration, portability, and end-to-end digitisation have clearly strengthened delivery, even if inefficiencies persist.

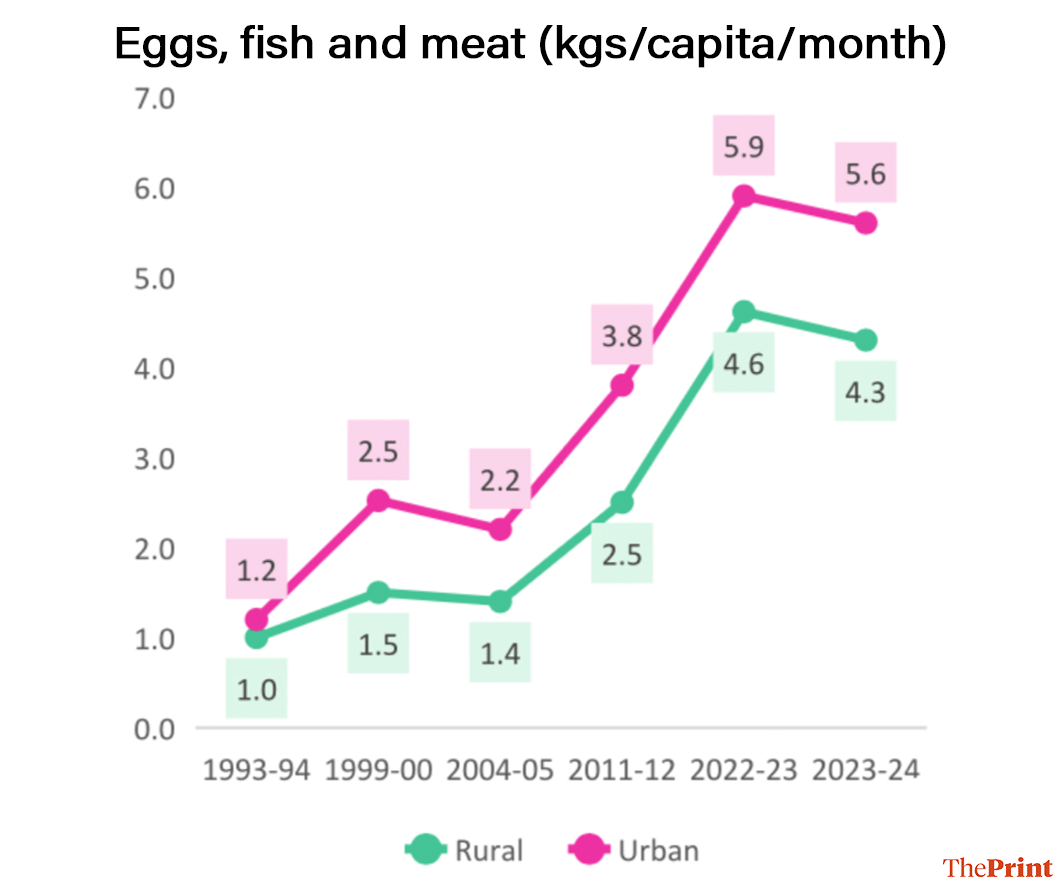

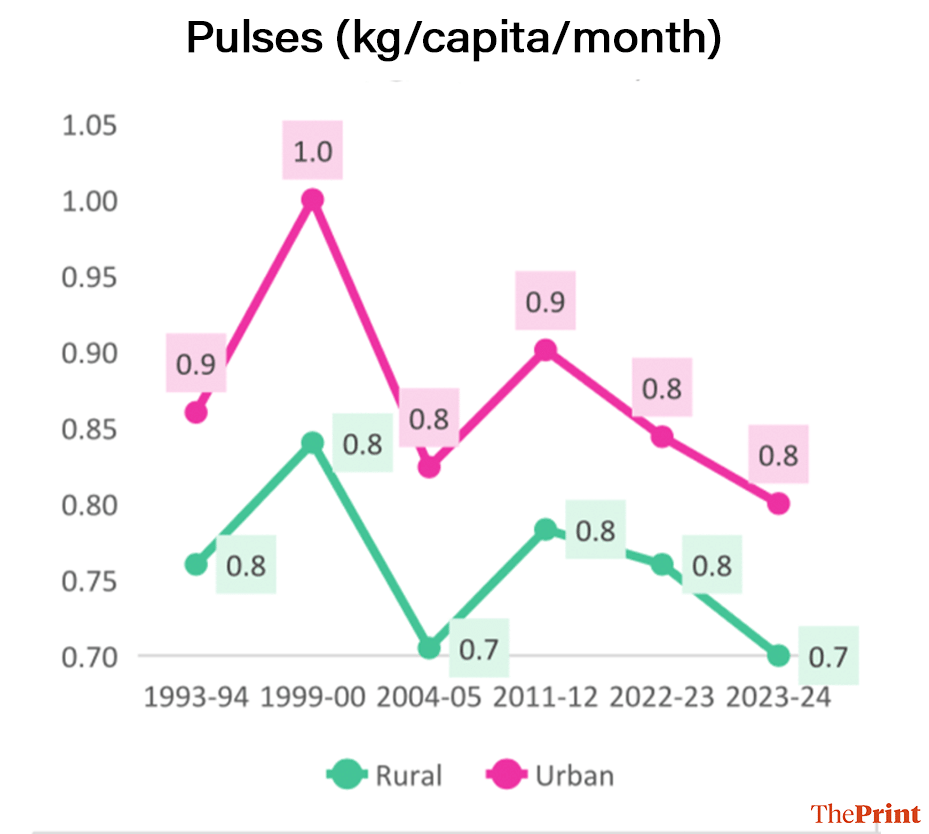

- At the same time, Indian diets have shifted decisively. As per MOSPI’s Household Consumption Expenditure Survey (HCES), the average monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE) on cereals has fallen sharply over the past three decades, while that on fruits, vegetables, milk, and animal-source foods has risen rapidly, especially in urban areas. Indian pulse consumption, however, has declined, reflecting continued issues around its sustained affordability (Figure).

- A deeper flaw lies in the static nature of NFSA beneficiary lists amid a rapidly changing deprivation landscape. Poverty has fallen to about 11 per cent in 2022-23, according to NITI Aayog. Multidimensional poverty has declined sharply, and nutrition indicators have improved across National Family Health Survey (NFHS) rounds. Yet NFSA beneficiary lists remain largely frozen, updated neither to reflect households that have exited poverty nor to accommodate those who fall into temporary or recurrent distress. As a result, many non-poor households continue to receive subsidised grain, while newly vulnerable families, pushed into distress by health shocks, climate events, or job losses, risk exclusion.

- India’s experiments with Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) for food have evolved and today offer clear lessons. Apart from several pilots, India tested DBT-for-food on a relatively larger scale in multiple settings like Chandigarh, Puducherry, Dadra & Nagar Haveli, and most recently, Karnataka. Design varied drastically across these experiments, and so did outcomes. Our continuing evaluation of most of these programs yields a few key lessons.

DBT performed relatively better in urban and peri-urban settings with dense markets and high financial inclusion, but proved far less reliable in remote, climatically constrained, or thin-market regions, where ration shops functioned as essential infrastructure rather than mere delivery points.

Preferences also diverged across households: farmers were often willing to substitute grain with cash, while landless labourers and the urban poor valued the predictability and price insulation that physical grain provided. Crucially, fixed cash transfers repeatedly lost real value during food inflation episodes, exposing beneficiaries to price spikes in ways that in-kind support did not. We found little evidence of money being used for vices like alcohol or gambling. Instead, funds went to buying books, paying off smaller debts, buying eggs, fruits, or even better rice.

Also read: Atomic energy can be used for peaceful purposes, to the immense advantage of humanity: Nehru

What will be a future-ready PDS?

One thing is clear: India does not need a single, uniform food welfare model for the coming times. A future-ready PDS can therefore be guided by a set of clear design principles, rooted in evidence.

First, poverty will continue to decline, but vulnerability will persist. This implies that while headline poverty numbers are falling, millions of households are likely to remain one shock away from food insecurity. This makes a static beneficiary architecture increasingly misaligned with reality. PDS must therefore revisit its beneficiary lists with a fixed frequency to correct for both exclusion and inclusion errors.

Second, the government may consider PDS to return to differentiated support. The poorest households under Antyodaya Anna Yojana (AAY) should continue to receive fully subsidised food, while others can be supported through calibrated, partial subsidies instead of blanket entitlements.

Third, cereals alone can no longer define the food floor. Grain support remains essential, but the AAY basket must gradually expand to include pulses, and, where feasible, regionally appropriate nutrition additions. Experience from states such as Tamil Nadu and the Centre’s own pulse distribution during Covid-19 shows that diversification within PDS is administratively feasible when backed by political intent.

Fourth, PDS must support the vulnerable without substituting markets. The distribution system was built to guarantee a food floor, not to fill the entire plate. That floor once meant rice and wheat, and for the future, it could just as legitimately include pulses or millets.

Fifth, cash versus grain should not be treated as a binary choice. India’s DBT-for-food experiments show that outcomes depend on design and context. A future-ready PDS must therefore enable choice where markets are deep and access is reliable, rather than impose uniformity.

Where cash is used, it must be inflation-indexed, unconditional, and paid to the woman head of household to preserve real value, dignity, and agency. India’s food subsidy bill of nearly Rs. 2 lakh crore in 2024-25 offers a realistic benchmark: spread across beneficiaries, it translates to about Rs 2,400 or Rs 2,500 per person or about Rs 12,500 annually for a household of five- an amount that can guide calibrated cash support where conditions favour DBT, without compromising food security.

Finally, states must lead with local nutritional intelligence. States understand their populations’ dietary gaps, agricultural base, market access, and logistical constraints far better than any national template. Discussions on PDS rethinking, therefore, should involve states and UTs.

Overall, PDS has to reform and become future-ready. The question is not the cost of reform, but the cost of delay.

Shweta Saini is CEO, Arcus Policy Research, and T Nandakumar is a former Secretary for Food and later for Agriculture, GOI. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)