As the Union Budget approaches, the agricultural sector is once again being highlighted as an area that requires protection. This perspective is understandable; however, it is also deeply limiting. Agriculture should not be perceived merely as a welfare obligation or an issue of inflation management. It represents one of India’s most underutilised avenues for growth reform and, importantly, the most cost-effective option available to the state.

The underperformance of India’s agricultural sector is frequently attributed to structural constraints like small landholdings, climate stress, and demographic pressure. While these factors are indeed significant, they do not fully account for the stagnation in productivity growth, even in regions with access to irrigation, markets, and policy support.

The deeper issue is both simpler and more disconcerting: agricultural incentives have remained static over time. When incentives cease to evolve, growth does not abruptly collapse overnight; rather, it gradually deteriorates. This degradation is most evident in India’s oilseed economy, particularly in mustard.

When growth slows, biology speaks first

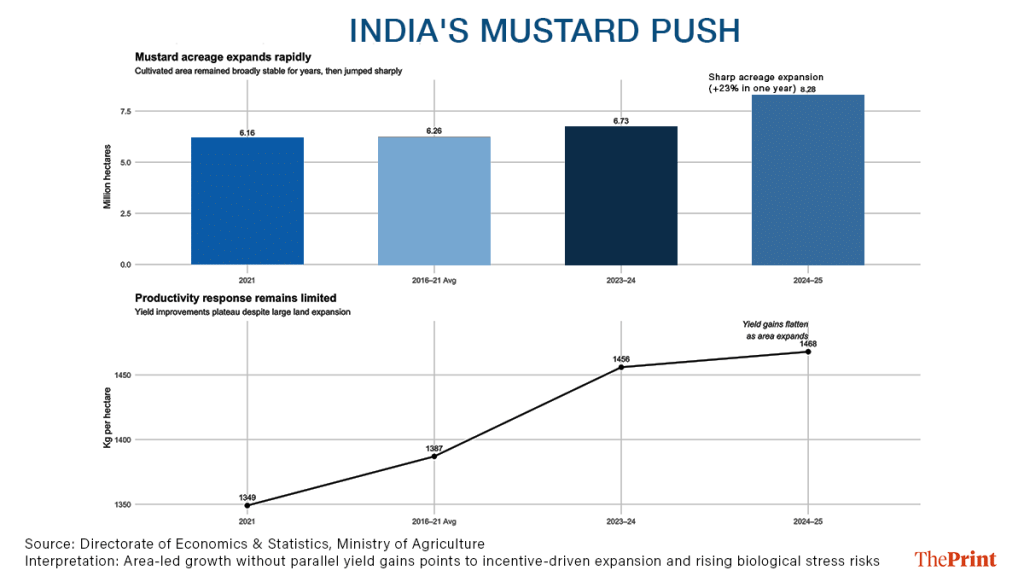

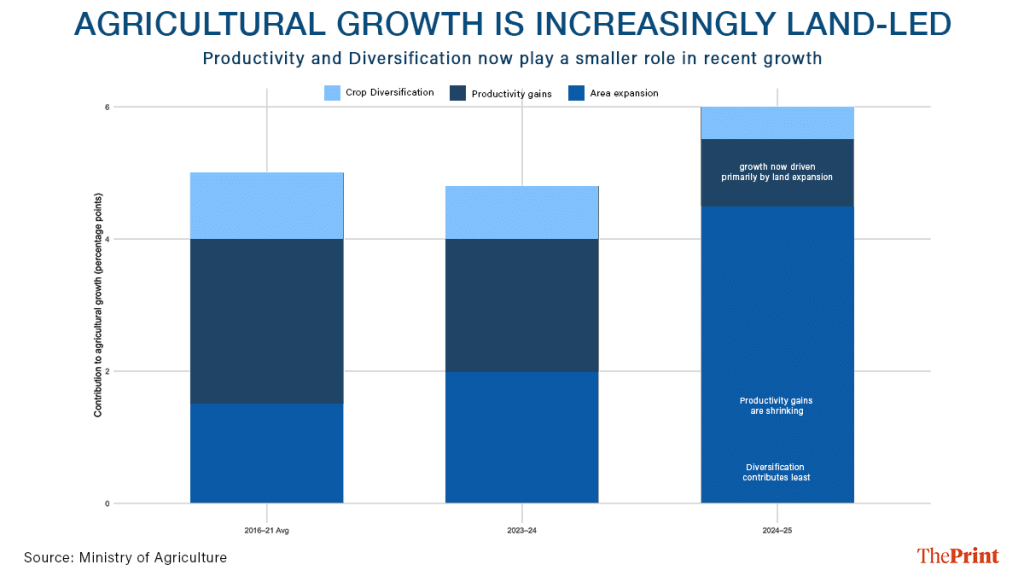

India’s recent agricultural growth has predominantly resulted from the expansion of cultivated land rather than enhancements in productivity. This phenomenon is indicative of a system that no longer rewards innovation. In such systems, stress accumulates subtly until it manifests as soil degradation, increased pest pressure, or yield instability. Mustard cultivation offers a revealing case. It occupies approximately 9-10 million hectares and is central to India’s efforts to reduce dependence on imported edible oils.

Recently, the expansion of mustard acreage has been driven by increased minimum support prices and repeated policy signals promoting oilseed self-reliance. However, this expansion has not been accompanied by corresponding improvements in procurement predictability, crop rotation incentives, or agronomic support. Consequently, farmers have responded logically by increasing mustard cultivation, often repeatedly.

This has led to biological repercussions, notably the spread of Orobanche, a parasitic weed that attaches to mustard roots, reported across major cultivation areas. Field studies indicate yield losses ranging from 20 to more than 60 per cent in affected plots. Once established, Orobanche seeds can persist in the soil for years, thereby increasing long-term risks and input costs. This situation is not merely an agronomic anomaly but a warning signal.

When policy encourages farmers to diversify without addressing risk management, farmers tend to intensify rather than adapt. The system thus rewards short-term land expansion while quietly accumulating long-term vulnerabilities.

The chart makes visible what policy often misses: incentives that appear growth-oriented can, in practice, undermine resilience when they are incomplete.

Also read: India has an import dependency problem. What Budget 2026 can change

Frozen incentives, predictable outcomes

Farmers are often characterised as risk-averse. In actuality, they are responding to a policy framework that mitigates price risk for a limited range of crops, while leaving biological, climatic, and market risks largely individualised in other areas.

As a result, diversification remains rhetorically appealing but economically fragile. Transitioning from cereals into oilseeds, pulses, or higher-value crops exposes farmers to price volatility, procurement uncertainty, and sudden policy interventions. Under these conditions, adhering to familiar crops or repeating a newly promoted one becomes the safer option.

The implications extend beyond individual crops. Regions entrenched in monocultures experience diminishing marginal returns, increasing ecological stress, and escalating fiscal costs for the state. In contrast, where farmers have access to stable market signals, such as horticulture belts, dairy clusters, and aquaculture zones, productivity and incomes rise without corresponding increases in public expenditure.

This contrast reveals a broader truth: agricultural growth does not stagnate because farmers resist change; it stagnates because the system renders change irrational.

Growth pathways exist, but policy treats them as exceptions

In contemporary India, the most dynamic sectors within agriculture are not the traditional cereal crops, but rather dairy, poultry, fisheries, shrimp aquaculture, and high-value horticulture. These sectors contribute an increasing proportion of agricultural value added, despite their relatively minimal land usage.

The distinguishing factor of these sectors is not the intensity of subsidies but rather their incentive structures. They benefit from clearer market mechanisms, greater private sector involvement, and reduced policy interference. These conditions enable farmers to transition out of low-productivity equilibria rather than remain confined within them.

However, policy frameworks continue to regard these successful sectors as peripheral rather than foundational. Instead of emulating their incentive structures, the state allocates fiscal resources to address the symptoms of stagnation in other areas, such as pest compensation, surplus storage, emergency imports, and recurrent price interventions.

This chart captures the core diagnosis. Growth driven by acreage expansion is a warning sign, not a success story.

Also read: Don’t mistake India’s economic recovery for a new era of rapid growth

What the Budget should do differently

The primary consideration for the Union Budget should not be the extent of expenditure on agriculture, but rather the types of behaviours it aims to incentivise.

First, the Budget should transition from episodic encouragement to establishing credible predictability. Farmers require assurance that policies will remain stable and not be abruptly reversed when prices increase, rather than consistently high prices. Implementing rule-based trade responses, transparent procurement thresholds, and time-bound support windows would facilitate diversification more effectively than recurrent ad hoc interventions.

Second, diversification should be approached as a risk-management strategy, rather than a moral imperative. Practices such as crop rotation, mixed farming, and transition to oilseeds or protein crops necessitate initial protection against biological and market risks. Investment in extension systems, early-warning mechanisms, and agronomic research should be considered essential growth infrastructure rather than peripheral expenditures.

Third, Budget priorities should shift from managing surplus to facilitating transition. Every rupee allocated to storing excess grain or compensating for avoidable shocks is a rupee not invested in enhancing productivity or resilience. The cheapest reform is often the one that prevents costs rather than distributing them later.

Agriculture represents India’s cheapest growth reform because it does not require new land, radical technology, or substantial fiscal expansion. It requires allowing incentives to evolve and trusting farmers to adapt. The warning signs are already evident in India’s fields. Whether the Budget chooses to read these signs as a crisis or an opportunity will determine the extent of growth agriculture can still achieve.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)