India’s universities might be divided by state, language, and affiliation, but they speak in one voice when it comes to dealing with sexual assault on campus.

Last week, a B.Tech student underwent a harrowing assault at Delhi’s South Asian University—and the administrators executed the expected institutional response flawlessly. They instructed the survivor to bathe and, in the process, destroy forensic evidence. They discouraged her and other students from contacting the police. And then, when protests broke out on campus, they assured the students that they would manage the crisis internally.

Eventually, a fellow student finally contacted the police the following day. According to the FIR, the survivor was being threatened and stalked in the days leading up to the attack. Four men assaulted her at an isolated, under-construction area at the university; they even attempted to get her to ingest a pill. The institutional machinery was activated when the visibly traumatised survivor returned to her hostel in torn clothes—to contain fallout.

First, the hostel authorities refused to meet her at night, and suggested that they would come the following morning. When the survivor attempted to reach out to her parents over the phone, they blocked her from doing so. Instead, they derailed the narrative, by telling her parents that she was having a panic attack. A purported audio recording from the hostel caretaker, Anupama Arora, gets progressively worse with each sentence: “Have you seen how her clothes are torn? Cloth tears differently when pulled. It looks like it was cut with a blade. Someone she knew must have called her, that’s why she went there. How can any girl go alone? I am completely sure that she went to someone she knew. I have been here for 15 years. Such a case has never happened here.”

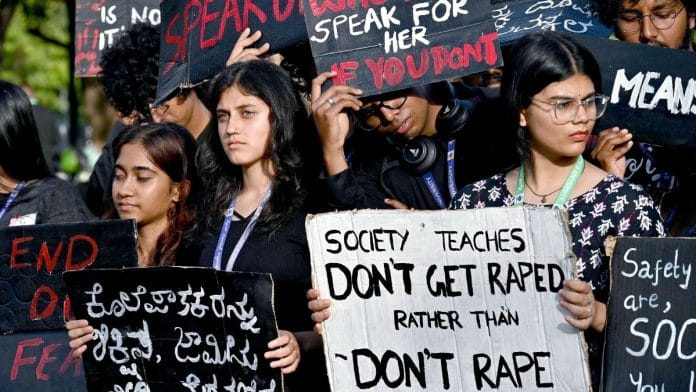

Students who later protested these actions demanded the suspension of hostel staff for attempting to “bury the incident and blame the victim”, a charge that the administration’s own conduct has already confirmed.

Also read: RG Kar and Sharon Raj verdicts are saying something about who we are. And it’s not good

Damage control

A sexual assault crisis is unfolding, across our higher educational institutions. It is bad enough that our campuses are demonstrably dangerous—as all public and private places in India tend to be. Some of the most prominent and horrifying cases of sexual violence over the last year have been reported from our colleges and universities, including the rape and murder of a junior doctor at RG Kar Medical College in Kolkata and the IIT-BHU gang-rape in Varanasi. Over the last fortnight alone, women students have been assaulted in Durgapur and Bengaluru.

Not only do our students have to be on guard in these predatory grounds, they must also reckon with the institutional response that treats every assault as if it’s happening for the first time. Despite well-established guidelines that define the approach to sexual assault, universities scramble and deflect. They “review” protocols and hurriedly set up committees that issue solemn promises of “zero tolerance”. Nothing changes.

The institutional default is not the protection of students and staff, but damage control. At SAU, IIT-BHU, RG Kar, and Durgapur, administrations have sought to suppress reports and discourage external intervention. When survivors and their allies inevitably protest, they are disciplined and attacked for disrupting the academic environment. This script plays out with such fidelity, you’d think everyone was drawing from the same crisis manual.

You only have to dial as far back as last year to see this play out. At IIT-BHU in 2023, the three men accused of gang rape fled to Madhya Pradesh immediately after the incident. There, the accused, who were identified as BJP IT cell members, participated in election campaigning. They returned nearly two months later, confident that nothing would happen because student protests had subsided. They were arrested, and eventually released on bail. The university’s response to this bungling? It instituted a standing committee that suspended 13 students for “indiscipline” during their protests demanding justice.

They fared only slightly better than the protesting doctors at RG Kar Medical College, who were attacked by a violent mob that destroyed the hospital’s emergency room. The college’s former principal, Sandip Kumar Ghosh, accused of mishandling the investigation, resigned amid protests. He stated that he was unable to endure the humiliation from social media criticism—only to be immediately appointed to another medical college.

Also read: IIT-BHU campus has changed for women after student gang rape. Life stays the same for men

Price for sexual violence

You’d think, given the frequency and horror of these incidents, that universities would have developed robust, survivor-centric systems by now. Elected redressal committees and regular workshops that walk students through reporting mechanisms. Communication campaigns directed at male students, warning them of the severe consequences of sexual misconduct. And actual, unambiguous punishment for such crimes.

Instead, our institutions have honed in on exactly one response: Locking up women. The price for sexual violence is paid for by the gender suffering the violence in the first place. In the aftermath of such an incident, curfews and restricted hostel timings become routine. Women students’ mobility and autonomy are heavily policed—they are called upon to surrender their freedom in exchange for fictive protection. But isn’t shrinking the radius within which women are allowed to exist an admission of a university’s failure?

On paper, India has built a comprehensive legal framework to address campus sexual harassment. The Vishaka guidelines were codified into the POSH Act in 2013, and applied to higher education through the UGC’s 2015 regulations. Universities are mandated to establish Internal Complaints Committees and organise gender sensitisation programmes.

Even a great framework, however, falls flat without intention. The clearest example of this institutional gutting is what happened with Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Gender Sensitisation Committee Against Sexual Harassment. The diverse, elected body had functioned since 1999 as a model for universities nationwide. It was dissolved in 2017 and replaced with an administration-nominated ICC.

Contrast this with how universities in the US and UK handle campus sexual assault. Under Title IX, American institutions are legally required to provide immediate interim measures (like no-contact orders and class schedule adjustments) that minimise the burden on survivors. In the UK, as formal investigations proceed, universities take concurrent administrative action to protect a survivor’s environment. All of these systems are hard-won examples of institutional accountability.

Also read: Anna University rape case—the ‘Sir’ who was never unmasked, to a rare, quick conviction

Gross sensationalism

But why blame our universities and colleges when they’re only mimicking the priorities of our politicians, the executive, and the media?

They take their cues from political leaders, who, regardless of ideology, consistently resort to blaming the victims. When West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee responded to the Durgapur assault by asking “How did she come out at 12.30 am?”, it wasn’t even the first time she had shifted scrutiny from the perpetrator to the victim. On this one count, Banerjee is united with her bitter rivals in the BJP, who have suggested that girls who use mobile phones invite sexual assault. Samajwadi Party leader Abu Azmi argued that women who go out with men who aren’t their relatives should expect to be raped.

The media completes this circuit through gross sensationalism. TV coverage of the RG Kar case, for instance, descended into grotesque, salacious spectacle. Channels fixated on the erroneous detail of “151 grams of thick fluid”, found in the victim’s private parts. Zee News invited volunteers to demonstrate polygraph tests. Aaj Tak went so far as to debate how many men might have been involved in the assault.

The needle has barely moved in the last decade. The RG Kar case unfolded 11 years after the 2013 Shakti Mills gang rape in Mumbai, where media outlets violated basic protocols with complete impunity. Journalists lied their way around the hospital where the survivor was admitted, hoping to get a glimpse of her. One even climbed 13 floors to get past the police barricades. Photographers attempted to take pictures, even though identifying a survivor of a sexual crime is against every regulation.

When the survivor was required to identify her attackers during the Test Identification Parade, she had to touch each of the accused on the arm, then announce loudly in a room full of men, “Isne mera balatkaar kiya” (He sexually assaulted me). She repeated this four times, in the absence of any women officers.

This is what passes for due process in India’s institutions—because that’s how seriously they take sexual violence. Serious enough to mandate committees and guidelines, just not seriously enough to make them work.

Accountability would require consequences. Maybe penalties for officials who suppress reporting, or sanctions for universities that punish protesters. But who will bell that cat? No one. It costs institutions nothing to fail survivors.

Karanjeet Kaur is a journalist, and a partner at TWO Design. She tweets @Kaju_Katri. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

This piece is so heart breaking. I am from IIT-BHU and it really struck all of us when the gang rape happened in the campus. At the time, there was furore on Alumni chat groups and there were indications that due process may be followed. It is our apathy – my apathy – that I did not realize that the protesting students were under suspension after all this. At 20, I used to question why we don’t allow women to travel for better education – now, I think I understand. It is because no one in the system will back you up in case of a a crisis. Everyone is out to save their behinds.