Free enterprise, in the words of A. D. Shroff, “was born with man and shall survive as long as man survives”. It is an offspring of the quest for freedom, a live rendering of the longing in human heart to shape one’s affairs unhindered by official cramps The freedom to disseminate ideas, opinions and concepts, the freedom to treat with complete candour the various aspects of human life and activity, and the freedom to voice one’s aspirations and feelings are vital to progress in a free society. Freedom of enterprise is one step ahead of the freedom to disseminate ideas, still the two have a close nexus and are linked with each other.

Nothing brings law into greater disrepute and breeds [a] stronger feeling of defiance than an attempt on its part to make men see opinions which they hold for true, regarded as crime. Likewise nothing creates greater frustration and dismay than the mandarin obstruction to any venture marked by spirit of initiative and enterprise. Freedom at the same time is not and cannot afford to be allergic to all restraint. It indeed needs some restraint for its own survival. As such there is no conflict between restraint per se and freedom. The real conflict is between the restraint that cramps the personal life and the spiritual order and the restraint that is aimed at securing the external and material conditions of their free and unimpeded development.

The essence of freedom lies in the unhampered development of the personality of each individual so that the efflorescence of his faculties might lead to satisfactory harmonisation of impulses. Restraint degenerates into an attack upon freedom where it stifles such development. Any restraint which frustrates life and spiritual enrichment must be looked upon as an evil. The world has a certain stock of knowledge, which has been garnered through the toil of succeeding generations of men. Each generation as the successor of the earlier generations has a right to put that knowledge to use. It is not wise under the garb or because of any notion of paternal supervision to deny opportunities to individual members of the society from pushing the bounds of that knowledge further and harnessing it to proper use. All that has to be ensured is that in doing so the individual does not impinge upon the rights of others or commit breach of any provision for the benefit of society as a whole.

Any talk of freedom inevitably takes our thoughts to the courts and judges, for through the course of years and in the corridor of time they have acquired the image of being sentinels of human freedom and guardians of basic rights. Whenever, therefore, there is a mission of freedom and infringement of rights we turn to the courts and judges to provide redress. Indeed it is the capacity of the judges and the courts to provide redress in such cases, which furnishes the real index of the prevalence of the rule of law as against the rule of men.

But courts and judges have not always satisfied that test. Past history of mankind and contemporary world are not lacking in instances when law has been used as an instrument to abridge or extinguish freedom instead of expanding its frontiers and the machinery of courts has been used to exterminate the political opponents and silence the voice of dissent.

While ideals of justice and the concept of over-riding rule of law have at times helped to limit arbitrary and unjust rule, it is also unfortunately true, as observed by a discerning writer, that great and systematic iniquity has been done by men who claimed to be acting under law and whose actions were facilitated by institutions like legislatures and courts that we would generally characterise as legal. Nothing suits dictatorship more than a subservient judiciary willing to carry out its behest. The totalitarian states indeed are never tired of claiming a legal basis for their action and are too eager to make use of conventional legal institutions to further their ends. Justice then has to bow out because the court in such a situation becomes an instrument of power.

Judges are soldiers putting down rebellion and a so-called trial is nothing more than a punitive expedition or ceremonial execution — its victims being Joan of Arc, a Bruno or a Galileo. It is for this reason that all lovers of freedom have also espoused the cause of a strong and independent judiciary, of having persons on the Judge’s seat who would not falter or swerve from the ideal of administering justice without fear or favour, whatever may be the pressure and however great the temptation. Weak minds and timid characters, they know, ill go together with the office of a judge.

The title, “Reform of the Judiciary” should not lead us to suppose that there is something basically wrong with the judiciary and it calls for radical and wholesale reform. By and large the judiciary, especially the judiciary in India, has maintained high standards. Speaking as I am to an audience in the city of Bombay, I have no doubt that most of you would agree having had experience during post independence years on Bombay High Court of a Chief Justice who though now frail in health is strong in will and epitomises within himself the great and noble traditions of judiciary. At the same time it would not be realistic to shut our eyes to some of the infirmities which have crept into the judiciary and made themselves manifest.

It is apposite that the question of reform not only of the judicial system but of the judiciary is engaging serious attention. We are today passing through an age of social questioning. There is all round a spirit of iconoclasm. The gods we worshipped till yesterday have been slowly and gradually dethroned from the minds of the people. No institution can take for granted the reverence of the community. The community demands from every institution the justification of its existence, the proof of its utility. There was, at one time, an aura about the judiciary. It created a sense of there being something mystique about it in the minds of the people. Under the cover of that, we could hide some of the short-comings and drawbacks of the institution.

To some extent, we in the world of law have thus thrived on the ignorance of others. Such a time is now past and no more. The legal institutions and the courts have to earn reverence through the test of truth. They cannot brush under the carpet criticism, if true, however unpalatable it may be. It may become essential to do a bit of heart-searching and indulge in a bit of introspection. If, in the process, we discover drawbacks and infirmities, enlightened self-interest demands that we should set the same right.

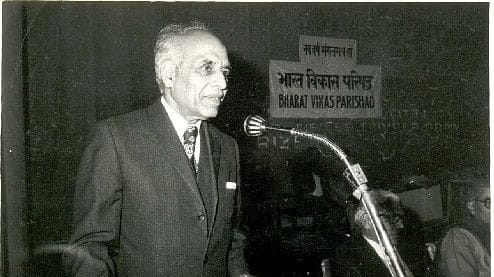

This essay is part of a series from the Indian Liberals archive, a project of the Centre for Civil Society. This essay is excerpted from a lecture delivered by Justice HR Khanna, former Judge of the Supreme Court of India, as part of the AD Shroff Memorial Lecture under the auspices of the Forum of Free Enterprise, on 13 October 1980. The original version can be accessed here.