India’s Defence Acquisition Council cleared the proposal for the procurement of Future Ready Combat Vehicles last year. These vehicles are supposed to be a “futuristic Main Battle Tank with superior mobility, all terrain ability, multilayered protections, precision and lethal fires and real-time situational awareness”. According to reports, the 57,000 crore project will induct 1,770 modern Main Battle Tanks to replace the Indian Army’s ageing T-72 fleet.

However, in light of the unprecedented challenges due to the rise of ‘transparent battlefields’ enabled by ubiquitous Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR), as exemplified by recent experiences from the Russia-Ukraine war and Nagorno-Karabakh, the Indian Army must reassess the utility of MBTs in future war fighting.

Any decision to invest in future Main Battle Tanks (MBTs) must take into account five factors: MBTs’ role within the existing military doctrine; their suitability to the ‘terrain’; survivability against emerging threats; their economics, acquisition and procurement, life-cycle costs, and industrial lock-in; and their substitutability or replaceability, functions or platform.

Role within the doctrine

Historically, tanks were designed for high-intensity offensive manoeuvre: smashing enemy lines, exploiting breakthroughs, and working in concert with infantry and artillery. India’s official doctrine has long been armour-centric. The 2018 Land Warfare Doctrine envisions the swift application of force on the western front to “destroy the centre of gravity” and secure spatial gains.

In the northern front, it emphasises deterrence, force-centric operations, multi-tiered deployment and rapid mobilisation. Within this doctrine, MBTs are central, forming the armoured corps and the core of Integrated Battle Groups (IBGs). The tanks are assigned both offensive (mobile firepower, territory capture, and covering infantry) and defensive roles (holding enemy advances).

However, evolving battlefield characteristics and strategic realities question the utility of MBTs. A few queries need answering. Are conventional wars plausible with China and Pakistan? Is imposing punitive incursions realistic? What are the political objectives of territorial capture? Are MBTs the right tool to achieve those objectives?

The existence of nuclear deterrence and the lack of sufficient power differential in conventional land warfare capabilities vis-à-vis China or Pakistan limit the scope for old-fashioned large-scale territorial warfare to impose punitive incursions.

China and India have shown reluctance even for short conflicts. Despite a volatile Line of Actual Control (LAC), the two countries have worked to contain crises. Two reasons underpin this caution—neither side has a decisive power differential that would guarantee significant territorial gains, and the strategic costs of attempting to convert a likely stalemate into victory would far exceed any territorial prize.

From India’s perspective, China combines nuclear status with conventional superiority, making punitive incursions nearly impossible under current power differentials; a fact reflected in the doctrine’s muted language about “spatial gain” on the northern front.

Proponents may argue that MBTs remain useful defensively along the northern frontier, but that claim has limitations. Of MBTs’ core attributes — mobility, protection, firepower — mobility is least relevant in static defence. Using expensive MBTs as protective shields is economically inefficient. Their value, if any, lies in offence, not in stationary protection.

Furthermore, MBTs cannot cover large areas or formations. Defensive positions are better strengthened by leveraging terrain and natural obstacles, supported by artillery. Where MBTs could matter defensively is firepower, but this overlaps heavily with layered defensive systems already fielded — small arms, machine guns, rocket launchers, mortars, and towed artillery — diminishing the marginal utility of MBTs.

Against Pakistan, India enjoys a favourable conventional differential, but nuclear deterrence limits the scope for large-scale punitive incursions. Over the past two decades, expanding arsenals on both sides have created credible nuclear deterrence, constraining the space for conventional warfare. Pakistan has sought to expand sub-conventional options through state-sponsored terrorism under the nuclear umbrella. India has largely avoided large-scale counteroffensives – prioritising economic development, though it has used calibrated conventional responses (surgical strikes 2016, air strikes 2019, 2025). Even these actions suggest objectives short of occupying territory.

To sum up, the inadequacy of an overwhelming power differential in the conventional sense and the existence of a nuclear umbrella severely limit India’s capability to impose punitive incursion.

While China enjoys a positive power differential vis-à-vis India, the latter’s capabilities are adequate enough to enforce a stalemate. The same logic applies vis-à-vis Pakistan. While India enjoys conventional superiority over Pakistan, it is not significant enough to avoid a stalemate.

Also read: India’s exit from Ayni airbase reveals New Delhi’s power projection limits. A key location lost

Challenges in terrain

Terrain and geography are critical determinants of land warfare, especially for India, whose borders encompass diverse features — marshy, sandy, plain, and mountainous terrains — that profoundly affect MBT effectiveness.

The predominantly mountainous and forested terrain limits tank manoeuvrability and effectiveness across the LAC and Line of Control (LoC). These high-altitude regions, among the world’s highest battlefields, pose serious operational risks due to narrow roads, steep gradients, meandering features and extreme weather. MBTs’ limited situational awareness and large dimensions make them vulnerable to ambushes and portable anti-tank weapons. Guerrilla tactics in the mountains can destroy tanks from concealed positions. Furthermore, harsh climates also result in increased fuel consumption and frequent engine failures.

In the marshy and swampy zones of the India-Pakistan border, MBTs face mobility issues. The 1965 Battle of Asal Uttar is instructive in this regard. Pakistani tanks advancing into flooded fields were immobilised and destroyed by Indian forces. The same conditions could similarly impede Indian MBTs in future offensives.

Desert terrain presents yet another challenge. Operating in extreme heat above 50°C strains cooling systems, increases engine failures, and causes mechanical malfunctions. Sand infiltration into engines and barrels, as observed with Britain’s Challenger II tanks during the Saif Sareea 2 exercise in Oman (2001), hampers reliability and maintenance. India’s indigenous Arjun tanks, too, have struggled in desert trials, leading the Indian Army to express repeated dissatisfaction with Arjun. Additionally, soft sand bogs down heavy tanks and prevents concealment or quick repair.

The 1971 Battle of Longewala exemplified how sandy terrain can neutralise MBT advantages. Pakistani tanks, immobilised in soft sand and exposed in open terrain, were decimated by Indian anti-tank fire and air strikes. These experiences underscore that India’s varied geography — mountainous, swampy, and sandy — fundamentally limits MBTs’ operational effectiveness and reliability.

Threats

Recent conflicts also validate the vulnerability of MBTs on transparent battlefields with extensive empirical evidence. In the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Azerbaijani drones and loitering munitions destroyed approximately 70 per cent of Armenia’s tank fleet within 44 days. Russia has lost over 3,000 tanks since February 2022 — roughly a quarter of its pre-war inventory — primarily to Ukrainian drones, artillery, and ATGMs.

These destruction rates demonstrate that modern ISR-enabled precision fire creates battlefield conditions where MBTs become priority targets with catastrophic attrition, especially when encountering unfavourable terrain. China and Pakistan field similar capabilities, including extensive drone arsenals and networked sensor systems, replicating the conditions that devastated Armenian and Russian armour.

Both China and Pakistan also field extensive anti-armour capabilities, including advanced ATGMs (like China’s HJ-12 and Pakistan’s Baktar-Shikan) and lethal loitering munitions and armed drones (like the Wing Loong and TB2). The doctrine of “Systems Confrontation” employed by adversaries leverages networked sensors to quickly detect and target heavy armour, making massing tanks perilous. While India is seeking countermeasures like the Israeli Trophy Active Protection Systems (APS) and Electronic Warfare (EW) to jam guidance links, maintaining MBT operational viability demands increasing, potentially unsustainable, resource commitments.

Economics

Mounting threats and increasing vulnerability do not justify the disproportionate investment that MBTs demand. While these tanks have traditionally been one of the most resource-intensive assets in land warfare, it is concerning that the quality standards are never met despite massive cost escalation.

Arjun, India’s indigenously developed MBT, illustrates the economic problem clearly. A 2014 Comptroller and Auditor General report documented unit cost escalation from ₹17 crore in 2001 to ₹44 crore in 2009, with prices in 2021 reaching approximately ₹64 crore. Yet, the Army has expressed repeated displeasure with Arjun for failing to meet performance standards during subsequent desert trials.

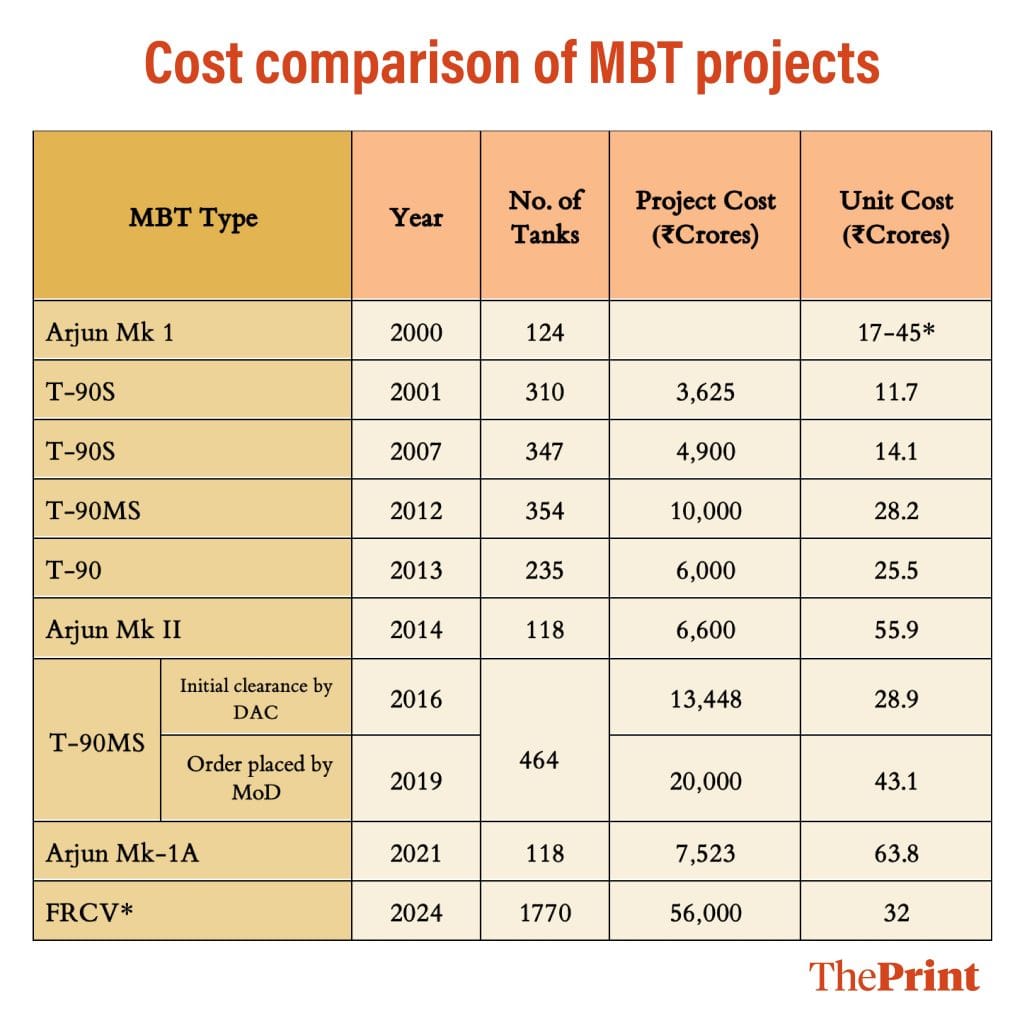

The table below provides a cost comparison of various MBT projects over the past two decades.

By the time the last unit was delivered, the cost had escalated from ₹17 crores to ₹45 crores

A review of the above table suggests that the ₹57,000 crore project to induct 1,770 Future Ready Combat Vehicles (FRCV), which puts the per unit cost at ₹32 crores, is a gross underestimation. Moreover, the costs indicated for Arjuns and T-90s in the table do not include the price of installing the Active Protection System (APS) and ERA Explosive Reactive Armour (ERA). The upgrades will further push the price. The latest available data suggest that Arjun Mk-1A is priced approximately at ₹70 crores. There is no way that the new FRCV, being touted as “futuristic MBTs with superior mobility, all terrain ability, multilayered protection, precision and lethal fires over and real-time situational awareness”, will cost a mere ₹32 crores per unit.

Moreover, the war in Ukraine and Nagorno-Karabakh has demonstrated that APS and ERA-installed MBTs are still vulnerable, thereby requiring further protective measures. Thus, fielding multiple near ₹100 crore platforms that become priority targets on transparent battlefields makes little economic sense.

As recent trends suggest, investments in the foreseeable future will likely be skewed towards MBTs’ protective systems to enhance their survivability rather than increasing their lethality. This resulted in bulkier, slower, and prohibitively expensive platforms. Fiscal constraints and competing defence priorities further question their viability.

A modern 155mm artillery system costs ₹15-30 crore, delivers greater range and lethality, and operates from protected positions. Miniature loitering munitions cost a fraction of an MBT but disable armour with precision. The issue isn’t just cost. It’s where the money goes. Funding poured into vulnerable platforms could buy counter-drone systems, long-range fires, cyber capabilities, and space-based ISR tools.

Also read: India’s defence acquisition framework is designed to prevent wrongdoing, not deliver outcomes

Substitutability and alternatives

Even if MBTs can contribute to offensive firepower, the question arises: are there platforms that can, unilaterally or in unison, replace these tasks for MBTs?

MBTs provide protected mobile firepower to penetrate enemy defences and fortifications. The critical question is whether existing or emerging platforms can perform these functions more effectively.

To begin with, artillery has become more accurate and precise over the past decades. The limitation with respect to gathering and relaying the requisite coordinates can also be overcome via real-time battlefield information. The cost and effort of achieving greater precision and reducing delays in artillery fire is far less than trying to make MBTs immune and insusceptible. Swift and precise artillery fires positioned safely behind forward lines eliminate the need for protected mobile firepower in exposed battlefield areas. Modern artillery with precision munitions and real-time targeting delivers overwhelming firepower without frontline exposure.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), drones and loitering munitions offer superior firepower, mobility, and survivability compared to MBTs. Anti-tank guided missiles effectively neutralise enemy armour at a fraction of MBT costs.

For territorial control and troop transport, light tanks, Infantry Fighting Vehicles (IFVs), and Armoured Personnel Carriers (APCs) provide adequate capability at significantly lower cost.

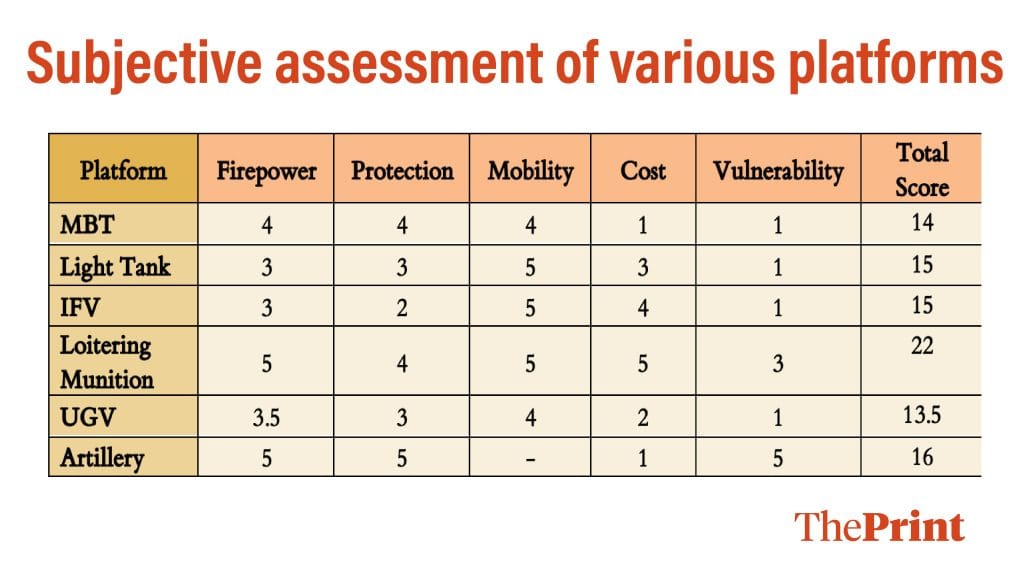

The following table offers a subjective assessment of various platforms that can either individually or in combination replace MBTs on the battlefield.

Each parameter is awarded a relative score on a scale of 1-5. Better the firepower, protection (shield and armour) and mobility, the higher the score. Alternatively, the higher the vulnerability and cost, lower the score.

China signalling a rethinking; India should too

A PLA daily piece recently highlighted that the “PLA is transitioning from the traditional close-quarters combat to beyond-visual-range combat, enabled by its new-generation main battle tank.” While the PLA may still refer to it as a new-generation MBT, the truth is that an MBT engaging in Beyond Visual Range (BVR) combat is artillery for all practical purposes.

The transparent battlefield — saturated with sensors, drones, and precision weapons — has turned MBTs into expensive liabilities. Conceived for industrial-age warfare, MBTs are losing relevance in the 21st century’s technology-driven battlefield. They have not meaningfully evolved since World War II and are increasingly “in search of a purpose.” India’s continued investment in heavy armour reflects institutional habit, not strategic logic.

Amit Kumar is a Staff Research Analyst, Indo-Pacific Studies Programme, at The Takshashila Institution. He tweets at @am_i_t_kumar. Satya Sahu is an Associate with The Asia Group’s South Asia practice in New Delhi. He tweets at @aytas_too_much. Views are personal.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)