Introduced as part of the Narendra Modi government’s aggressive measures last year to tame the spike in prices of pulses, it is time to review the open import policy of tur and urad. These pulses, in addition to chana and mung, have been trading below their MSP levels for a while now. With an open import policy till March 2023, the likelihood of prices rising this year are also grim.

Our assessment for kharif 2022 reveals a likely diversion of 8 to 10 per cent of pulses acreage to more lucrative crops like maize, oilseeds like soybean, and cash crops like cotton. But can India afford such a diversion? Successive governments have strategically invested in expanding pulses production. Given that the prices of pulses have now moderated, can the consumer bias in the policy now be turned around in favour of farmers? We analyse why this is important.

What happened last year?

Following deflation in the Wholesale Price Index (WPI) for pulses in 2017 and 2018, inflation started soaring at double-digits from February 2019. In 2020 and 2021, the price of pulses grew further. At the retail level too, double-digit inflation rates haunted 2020 and continued till September 2021. Pulses selling expensively included chana (gram), tur (arhar/pigeon pea), urad, masur (lentil), and moong, to some extent.

The sticky higher prices of these pulses spurred the Union government into motion. From March 2021 to March 2022, the Ministry of Commerce released 15 notifications regulating the trade of pulses. These were in addition to the domestic market regulations triggered by the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution. We list the major policy actions below:

- 19 March 2021: The Indian government extended the MOU with Mozambique to import 2 lakh metric tonnes of tur in FY 22;

- 15 May 2021: From ‘restricted’ category, tur, moong and urad imports were put under ‘free’ category till 31 October 2021. For moong, on 26 July 2021, the government reduced the basic duty to zero for all non-US imports (and to 20 per cent for all US imports);

- The free regime of ‘tur and urad’ import was extended till 31 December 2021, and thereafter till March 2022;

- 24 June 2021: The government signed two bilateral agreements with Malawi and Myanmar for import of tur and urad;

- 2 July 2021: Stocking limits were imposed on all pulses, except moong, under the Essential Commodities Act (ECA). All ‘excess’ stocks had to be offloaded before 31 October 2021;

- 26 July 2021: The basic import duty on masur was reduced to zero and the Agriculture Infrastructure and Development Cess (AIDC) was reduced to 10 per cent;

- In addition, the government also directed the National Agriculture Cooperative Marketing Federation of India (NAFED) to offload three lakh tonnes of gram from its existing stocks, in the open market until August 2021;

- 16 August 2021: The Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), suspended (till further orders) the launch of any new contract of chana on the National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange (NCDEX). In December 2021, SEBI suspended futures trading in several other agricultural commodities, including moong. These contracts continue to be suspended to date;

- 11 February 2022: Import policy for moong that was earlier ‘free’, was replaced to be under ‘restricted’ category;

- 29 March 2022: Free imports of tur and urad extended till 31 March 2023.

Also read: Cotton, other crops shouldn’t meet fate of wheat. Govt needs an empowered group

The result? Dal selling lower than MSP in wholesale

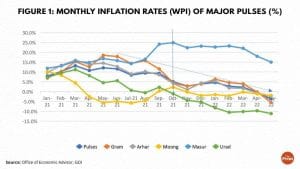

The price of most pulses, barring masur started to decelerate following the Modi government’s spate of policy actions (Figure 1). In the first half of 2021, average annual wholesale inflation rates ranged between 1.6 per cent (moong) and 13.5 per cent (gram). But since June 2021, these rates moderated and averaged between -1.7 per cent (moong) and 8.8 per cent (gram) (Figure 1). Masur prices have been an outlier all throughout and they continue to be high even now.

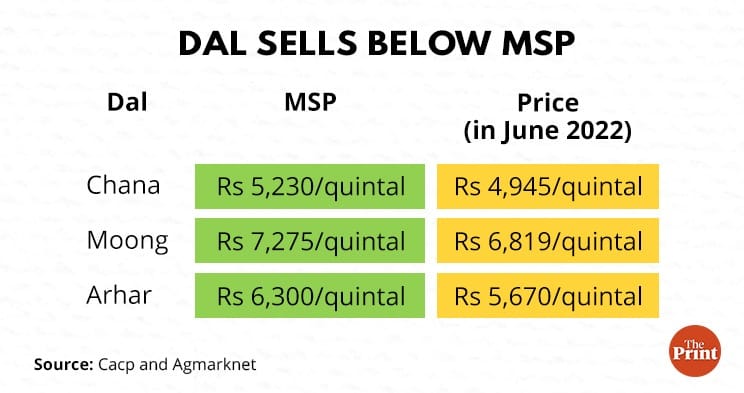

With falling prices, the situation now is that at the wholesale level, pulses are trading even below their respective MSPs (Table 1)

At the index level, pulses are recording a deflationary print. As per the recently released data on WPI and CPI for May 2022, annual inflation rates in pulses averaged -3.7 per cent at WPI and -0.4 per cent at CPI levels.

Due to low domestic prices, India’s pulse traders are now seeking export subsidies from the government. They are requesting a 10 per cent cash subsidy on chana exports. In these uncertain times when threats of food insecurity are pushing countries to impose restrictions on their exports, with India too imposing restrictions on its wheat and sugar exports, the pulse situation is rather intriguing, more so because we are a net importer of pulses.

Also read: Battling inflation & high fuel prices, 7 in 10 Indians against hike in GST rates, survey finds

Impact on acreage

Intuitively, subdued market prices and low chances of price rise in 2022 (due to the open import policy of tur and urad imports), are likely to push pulse farmers towards relatively more lucrative crops like maize, soybean, or cotton.

As per the data on ongoing kharif crop sowing, as on 17 June 2022, the acreage under pulses is lower by about 7.4 per cent compared to last year. The largest shortfall is visible in urad (28 per cent), followed by tur (9 per cent) and moong (7 per cent). Of course, with the delayed momentum of monsoon this year, these acreage numbers can be interpreted as being ‘in-progress’. But the question is, can India afford the fall in kharif pulses’ acreage?

What went wrong?

Last year, even though the government’s production estimate of main pulses like tur and gram (or chana) were 4.32 MMTs and 11.91 MMTs respectively (which were much higher than the previous year), private trade estimated the crop size to be much lower at 3.9 MMTs and 10 MMTs respectively. While the government maintained its high production estimates, its actions on the policy front reflected tacit acknowledgement of the smaller crop sizes.

This can mean two things. One, the government’s official public crop production assessments may be different from its own internal assessments. Two, in the last few years, pulses are not growing as fast as the government expected. This latter point is most critical and requires attention.

Also read: Weaker rupee, higher inflation — Why US Fed raising rates is more bad news for Indian economy

India needs its dal

Pulses are critical not just for Indian farmers but also for its consumers. With the revival of demand in the coming months, prices of pulses would likely see an upswing. But if acreage of pulses falls, then we may witness an even sharper rise in prices. Therefore, the government will do well in revisiting its policies for pulses before it is too late.

First, it has to ensure that the acreage of pulses does not fall much this year. Chances of gains from competing crops like soybean, maize and cotton are already likely to attract some of the farmland set out for pulses, but such a diversion should not happen because an open import policy is dampening income prospects for pulse farmers.

Also, an open import policy caps possible gains to a farmer suffering from growing pressures on the cost front, led primarily by expensive diesel, fertilisers, and land rentals. By subduing prices, a pulse farmer appears to be carrying the undue burden of subsidising the consumers.

India’s dependence on imported pulses is likely to continue in the near future too. But to ensure domestic farmers do not lose, governments can do well by ensuring that the landed cost of imported pulses does not fall below MSPs.

In addition to this, one thing is rather clear –India’s food surpluses are marginal. In light of the fast-changing reality of climate change, these surpluses cannot be taken for granted. We need to ensure that farmers continue to grow more pulses and this can only be done by ensuring remunerative returns for them. In the first term of PM Modi, the MSP of pulses was increased rather aggressively, but in the current term, MSP increase in pulses (barring masur) has been lower. The focus has increasingly been on oilseed crops like mustard, groundnut and cotton. Getting the pulse back is critical for Indian farmers and consumers alike.

Saini is an Economist and Hussain is former Secretary Agriculture to GOI. Both are promoters and Khatri is Consultant at Arcus Policy Research. Views are personal.

(Edited by Neera Majumdar)