The true strength of any country is its people. India is the most populous country in the world with an extensive reservoir of diverse talent that is globally recognised. A 2022 survey in the United States revealed that people of Indian origin, numbering about 4.8 million, were the highest earners, with a median income of $145,000, with an estimated annual income of approximately $700 billion.

Despite the global demand for Indian talent, its recognition within India is muted, to say the least. In my opinion, the myopic Indian mindset toward talent that led to the brain drain was the unintended consequence of the overregulated socialist economic policies that were pursued for decades.

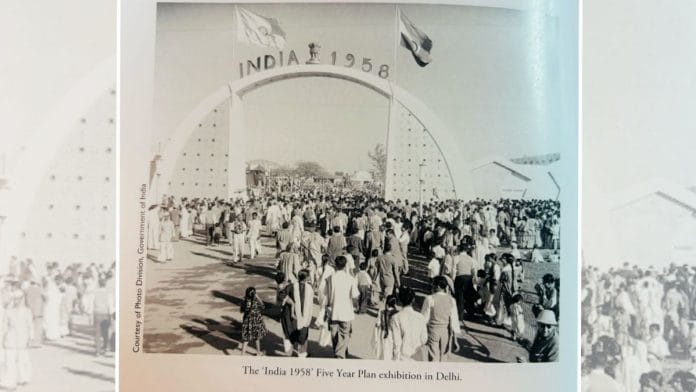

In the 1950s, policymakers rightfully recognised that industrialisation, growth, and development were of paramount importance for poverty reduction and nation-building. However, the difference of opinion lay in the means to achieve this end. The prevailing view among economists, policymakers, and industrialists at the time was that India’s economic problems were technical issues of optimal resource allocation. With appropriate data on the input-output matrix, the Indian economy could be planned, and the government could allocate scarce resources across different sectors of the economy to achieve the desired economic growth and industrialisation.

One such input in the grand scheme of things was the establishment of elite engineering and management institutions, funded by foreign aid and in collaboration with leading universities worldwide. These institutes were meant to create a regular supply of technocrats who would play a crucial role in the industrialisation process. What was perhaps the most remarkable feature, and the legacy of these institutions, is the highly competitive selection of students.

Unfortunately, the very planning that established these institutes paradoxically stifled the creative pursuit of the talent they produced, resulting in brain drain. The socialist planning of the Indian economy was not merely a strategic allocation of resources across sectors; it determined who would produce what and how much, popularly known as the “permit raj”.

What drove planning

The fundamental belief among the planners (economists and statisticians) was that high growth could be achieved through detailed central planning of the government. And the role of the chosen private sector players, it was thought, would be to do as the planners dictated. The ideological belief guiding the policymakers was driven by a complete mistrust of the private sector: that it would loot and plunder the helpless people of India if left unchecked.

While pursuing their noble goals, Indian planners and intellectuals completely ignored the lessons from an influential essay, ‘The Use of Knowledge in Society’, written by FA Hayek in 1945. It argued that the efficient allocation of resources requires knowledge (both quantifiable and non-quantifiable) that is dispersed among individuals. From a practical perspective, the relevant knowledge needed for efficient resource allocation cannot be communicated to the central planners. Moreover, the economic situation is not static; it is continuously in a state of flux. So, the key economic problem of allocation is the ability to “adapt to the changes”. Central planners lacking proper knowledge would be unable to adapt, and therefore, the allocation of resources would be inefficient.

The appeal of decentralised planning or letting economic decisions be made by individuals with local and specific knowledge was not ideological but practical. A “spontaneous order” would be created through the markets, and the prices would communicate the “dispersed, context-specific information” across society. Fundamentally, Hayek’s essay argued that the economic problem society faces is not a mathematical optimisation exercise that needs to be technically solved, but rather the understanding and creation of systems or institutions that promote “unknown people” who are most suited to a particular task.

During the era of grand central planning, the role of the private sector was highly circumscribed. It was either not allowed to grow, or the players that were permitted to be large were protected from competition (both internal and external). As a result of these socialist policies, fresh talent from the country’s elite engineering and management institutes had three choices:

- Join the elite Indian bureaucracy or the Public Sector Unit and execute the grand plan

- Join one of the large family-owned enterprises with minimal corporate governance and a lack of individual growth beyond a certain level

- Leave the country for greener pastures

Also read: Pushback against globalisation shouldn’t make us withdraw from it

Disasters of permit raj

The Indian planning system, based on “permit raj”, did not encourage individuals based on “what they knew”, but on “whom they knew”. Therefore, it was not surprising that many talented people from these elite institutions left India for countries that recognised their talent and gave them ample opportunities to flourish. The sad part of the brain drain was that the Indian taxpayers subsidised the exodus!

However, when the grand plans of the economy failed to deliver the desired results in terms of economic growth, prosperity, and poverty reduction, policymakers did not blame the central planning system. They arrived at the opposite conclusion: that there was not enough central planning. Ironically, the private sector was blamed for not making a meaningful contribution to the national objectives of poverty reduction and the development of small industries or the agricultural sector. Therefore, central planners felt a need to expand planning by nationalising the private sector, particularly the banks.

Unfortunately, the government’s Herculean efforts to plan the economy were disastrous. The desired level of growth and industrialisation was never achieved, and hundreds of millions of people were mired in poverty. The real cost of the planned economy was that it created rent-seeking opportunities for a lucky few who were privileged to be employed in the industrial sector, as they could not be fired. Interestingly, the planned economy also privileged a few large private players who were granted subsidised access to scarce capital, foreign exchange reserves, and were protected from foreign competition in the guise of an infant industry. As a result, the private sector did not invest in technology, produced substandard products, and, with all the feather nesting, had no incentive to become a global player.

The planned economy created a uniquely Indian industrial setup, which was dominated by many informal plants with minimal innovation and very few large plants. Ironically, the planned economy artificially inflated the cost of hiring labour in a labour-abundant economy. As a result, the majority of workers were trapped in low-paying jobs, working in small, informal firms that did not invest in technology, and therefore did not experience any productivity improvements for decades. While protecting labour, even before industrialisation had taken root, the planners unintentionally guaranteed that India remained an agrarian economy. The absolute folly of the planners, intellectuals, and thinkers during this era was the ideological belief that the Indian economy could be centrally planned.

Also read: India-China ties — improvement signs are loud, problems sliding under the radar

Results of IDA

The latest research examining this issue has revealed some interesting quantitative findings. For example, the Industrial Disputes Act (IDA) of 1947, which put severe regulatory constraints on large firms firing workers, had three disastrous effects:

- The most productive firms were much smaller than what they would have been

- Small and micro firms proliferated, with little scope for innovation

- A political class of privileged union workers (fortunate to get a job in the formal manufacturing sector) was created, who would militantly threaten any reforms that took away their rent-seeking opportunities

Interestingly, the IDA had a loophole that regulations regarding the firing of workers applied only to permanent workers and not to contract workers. Large firms could potentially bypass the IDA and overcome the artificial labour shortage, thereby expanding production by hiring contract workers. The central planners noticed the loophole and took stringent measures to plug it by passing the Contract Labour Act, 1970, which increased the regulatory burden of hiring contract workers.

Furthermore, in 1976, the IDA was amended to make it more stringent for firms to lay off non-managerial workers in plants that employed more than 300 of them. This threshold was reduced to 100 in 1982, and in some states, it was lowered to 50. Despite the liberalisation of the Indian economy in 1991, efforts to reform the IDA and the CLA were piecemeal, with little or no effect on the hiring of workers. However, in 2001, the Supreme Court, in a case involving the Steel Authority of India and the National Union Water Front Workers’ Union, passed a judgment that there was no requirement for the absorption of contract workers into the permanent workforce.

Research has shown that this benign judgment resulted in the following:

- The total factor productivity of Indian manufacturing increased by 7.6 per cent between 2000 and 2015

- The share of contract workers in plants with more than 100 workers doubled from 21 per cent to approximately 40 per cent

- The thickness of the right tail (segment with large plants that employ many workers) of the establishment size distribution in formal Indian manufacturing plants increased

- The average product of labour for large plants declined

- The job creation rate for large plants increased

- The probability that large plants introduced new products increased

Also read: A vicious pest is teaching Americans a lesson on why global cooperation matters

Removing small-scale reservations

Another policy that has limited the growth and employment potential was the reservation of certain manufacturing products for small-scale industries (SSI). Planners actively promoted SSI by providing them access to subsidised credit in the form of priority sector lending and protecting them from competition from large firms. The primary intention of the policymakers was to encourage job creation.

Careful empirical research has quantified the impact of such a policy on “employment growth, investment, output, productivity, and wages”. Interestingly, the researchers have shown that the results were the opposite of what the planners intended.

The dismantling of the SSI reservation policy led to:

- A 6 per cent increase in employment at the district level

- Labour shifting from the unorganised to the formal sector

- The product markets became more competitive, and smaller establishments entered and grew in size

- Among the small entrants, there was a substantial increase in labour productivity and wages

What is interesting about this result is that these small entrants would not need the dismantling of the reservation policy to enter the product markets, as they would be classified as small-scale. However, they voluntarily chose not to enter during this period because they were forward-looking and realised that under the reservation policy, they would not be able to grow beyond a certain level. Therefore, an unintended consequence of the good intentions behind the SSI reservation policy was the lack of competition, which created substandard products, suppressed labour productivity, and consequently, lower wages. Additionally, it curtailed employment.

Also read: World doesn’t need another China. Modi’s Swadeshi call shows why India holds the key

Lessons for the future

There are some fundamental lessons from the two policy experiments.

- We must identify economic policies that disrupt the competitive forces and take bold steps to dismantle them. The benchmark of economic reforms should be whether or not they make the economy competitive. Planning and protection of economic activity have neither led to growth nor employment but have instead created opportunities for rent-seeking and promoted corruption.

- The fundamental economic problem is designing institutions that allow an efficient use of knowledge (quantifiable and non-quantifiable) in society. This does not mean that the government has no role in economic activity. An appropriate size of government is needed to make markets efficient. For example, it needs to create institutions that can settle disputes promptly, enforce contracts, maintain law and order, and provide protection to life and property. The government needs to guarantee a minimum standard of health for all its people.

- When framing economic policies, we must not be blinded by ideological preferences but instead be guided by practical considerations. The discussion should be from an opportunity cost perspective, where we not only discuss the net benefits of the chosen policy but also account for the net benefits forgone by not choosing the alternative. For example, a credit subsidy policy to one sector has the opportunity cost of diverting resources from other sectors, so it becomes imperative not only to consider the benefits to the subsidised industry but also to account for the hidden cost of resource diversion from other sectors. In this sense, it is crucial to distinguish between accounting costs and opportunity costs. Failing to account for economic costs would be akin to counting the trees while missing the forest.

- We must recognise the political cost of economic reforms. For example, economic reforms might generate losses for the incumbents, and beneficiaries will exist in the future. Unfortunately, the losers will have political clout while the future beneficiaries do not have political representation (since they don’t exist yet). Therefore, a strong political will is required to initiate reforms. In a democracy, an agenda for economic reforms needs a political movement. Otherwise, reforms will only occur as a result of an economic crisis, which could be very costly.

- Excessive regulation of the economy, even with the noblest of intentions, from a practical perspective, only promotes opportunities for rent-seeking and corruption. Bad economic policies have an uncanny ability to persist, as they create a political class of beneficiaries who will do anything in their power to perpetuate these policies.

Shamika Ravi is a member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister and Secretary to the Government of India. Her X handle is @ShamikaRavi. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)

Honestly I was hoping that the Planning Commission would be wound up for good. Not reincarnated as Niti Aayog.

Dear author, Socialist Modi is choking India’s economy. Please advise him to follow free-market principles and reform land, labour, and capital. For the sake of the nation’s development, tell him to forget votes from the farmers and socialists and take hard decisions. The nation is diseased with socialism and needs deep treatment through a free market.