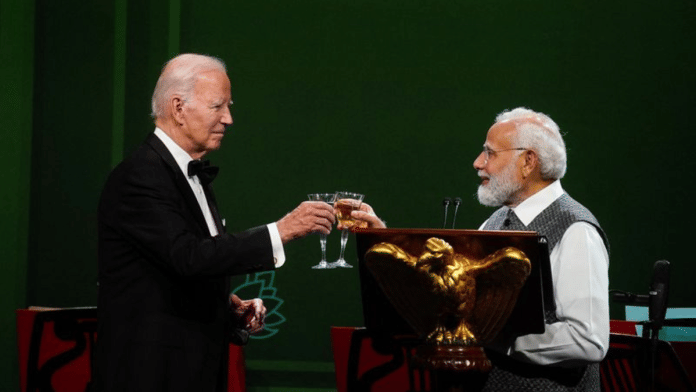

Notwithstanding ‘non-alignment’, ‘strategic autonomy’, ‘multi-alignment’ and such, there is little doubt that India’s relations with the US have deepened over the last two decades. The reason is also straightforward. Both Washington and New Delhi see a common interest in countering China’s growing power. Prime Minister Modi’s visit to America will further this.

But such a two-decade long overview, necessary as it is, misses the twists and turns in the ties. Whatever the broad strategic circumstances and security pressures, this was a relationship always subject to the vicissitudes of a variety of foolishness and political opportunism, especially from the Indian side. The nuclear deal, which was the basis for the new US-India relationship, barely survived the ideological tantrums of the communists and political opportunism of the BJP. And the Indian bureaucracy did its best to stall the basic foundational agreements. Indian over-confidence in managing China through formal and informal dialogues also impacted ties with Washington. If it were not for Xi Jinping’s ‘timely help’ in pushing along this relationship by periodically demonstrating its necessity, it is difficult to imagine that New Delhi would have travelled as far as it has.

And herein lies a key problem. Through much of the last two decades, it is difficult not to see this relationship as something in which most of the burden of pushing forward has been borne by Washington. That continues.

It again appears, looking at the various sets of agreements signed in this visit, that New Delhi has not invested much beyond a road show. Almost all agreements are references to various elements that the US provides. There is only one area, at least in a cursory first reading, that appears to be an effort made on the Indian side: ISRO joining the NASA Artemis Accords, which is useful but still marginal. Another, possibly, is underwater domain awareness, which appears to be the first time this has been mentioned. This is an extension of maritime domain awareness but a critical one. The rest are largely warmed over from previous agreements. For example, the placing of Indian military liaison officers in US commands was agreed to a few years back.

Though this can be seen as the success of Indian diplomatic skill — that it is able to get much more than it gives — two problems arise.

Also read: Modi-Biden talk of ‘values’ has one purpose. Strengthening the cause of democracy isn’t it

The unequal bargain

One, such an approach is bound to raise questions in the US, and is already doing so. The more the US gives, the greater will be the questions about what it gets in return. After the nuke deal, a number of senior US analysts and officials held up the prospect of India being stronger as a sufficient reward, even as they were disappointed by India’s failure to provide

more direct returns in terms of nuclear plants or arms deals. This time, with increasingly serious questions being raised by many of them about the place of liberalism in India of India’s democracy, the idea that a stronger India is a sufficient reward will become more difficult to sell. This has been hinted at by many traditional supporters of closer US-India relations.

This problem becomes even greater when the costs to the US rise. The costs referred to here are not just the direct costs such as technology transfers but also indirect costs, such as the political burden in Washington of having to defend the India relationship from critics who point to the growing illiberalism in India. Irrespective of what the Indian government or its supporters in India or elsewhere claim, the narrative about India’s declining political standards is now well established.

India’s growing illiberalism is an issue that no amount of bearhugs or irrelevant claims about mothering democracy will ever entirely remove. These will grow worse if India continues in this direction. Ashley Tellis, ever a supporter of closer India-US ties, suggests the US hopes that private communication on such issues are better than publicly castigating the country. Indeed, in doing so, the US probably hopes that they are giving India something to lose if it moves further in an illiberal direction. This means that the US government will have to repeatedly face questions and justify the India relationship as valuable despite these questions.

The US will have little compunction about partnering with an illiberal India as long as the country is strategically useful. This is where, to use an American expression, the rubber meets the road. If all India does, maximally, is defend the territory it still holds, will that suffice? It could be argued that even this can benefit the US as India can divert China’s attention from the east, the Pacific and Taiwan.

But India will do this irrespective of its relations with the US and irrespective of what the US provides for India. Why then should the US bear any cost to support India? American assistance can definitely help India in presenting a bigger challenge to China that complicates Beijing’s calculations. But questions on the benefits the US gets in return for its support are bound to rise as American costs rise.

Indian decisionmakers should realise that it is not in New Delhi’s interest that such concerns of the US become a burden on the relationship.

Also read: Attacking Modi in US shows IAMC using Indian Muslims as pawns

What Modi’s visit achieves

A more serious issue is what the US relationship and in particular Modi’s visit does in helping India build its capacity to counter China, which should be the primary strategic consideration for India. The various US-India agreements do move the relationship forward a bit, but not by much.

India’s focus remains on long-term power generation, in building domestic defence capabilities such as jet engines. This is necessary but insufficient. The long-term doesn’t exist if the short-term is not taken care of. This is something that India’s history with China should have taught New Delhi.

The short-term problem is dealing with China’s military challenge at the LAC, for which greater security cooperation such as serious military-to-military discussions about plans, contingencies and support activities as well as preparations are necessary. For example, friendly support during military confrontations requires partners to know the specifics of what equipment needs replenishing – an obvious problem that India has repeatedly faced. It could go well beyond this, including closer discussions regarding China’s military operational capacities, tactics and vulnerabilities and other aspects of military operations. It could also include diplomatic strategies for such contingencies. Discussions about warplanes and military equipment largely miss this much more vital aspect of military cooperation and support.

Maybe it’s because India is confident that it can handle China on its own and doesn’t need US help at the border or elsewhere, beyond intelligence and technological support and some niche equipment. Indian foreign minister S. Jaishankar has claimed that India was strong enough. He could very well be right, of course, except that it’s difficult to trust such assessments when India has been wrong about China so consistently over the last decade, whether it was on the initial outreach to Beijing, or the informal dialogue after the Doklam confrontation. That China is one of the more serious blind spots in Indian strategic thinking, with a history of mistakes going back to the 1950s, is no excuse.

The long-term trajectory of the relationship with the US looks good, if India can avoid shorter-term dangers.

The author is a professor of International Politics at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi. He tweets @RRajagopalanJNU. Views are personal.

(Edited by Anurag Chaubey)