The India-Europe free trade agreement is set to accelerate trade between nearly two billion people. Beyond the long shadow of colonialism, the FTA is a reminder that there was and is much more to India-Europe ties than the difficult legacies of colonialism.

Over the thousand years between the end of the Roman Empire and Vasco Da Gama’s arrival, India was constantly present in Europe—in exchanges intensive, lucrative, and endlessly imaginative.

India as a symbolic Other

Recent scholarship and archaeology have substantially corrected the perception that India was an impoverished colonial periphery of Europe. Excavations from the Red Sea coast and trade documents establish India as a major exporter of luxury goods to Europe in the early centuries CE. In this period, Indian merchants and ‘diplomats’ occasionally appeared in Alexandria (Egypt) and even Rome. But after the turbulent migrations between the fifth and eighth centuries, trade routes shifted and new polities formed, leaving much of Europe under the control of Germanic tribes, while the Red Sea and Persian Gulf were dominated by Arab and Persian Muslims. Hereafter, European and Indian sources rarely mention direct contact between the regions. But indirect contact continued to flourish.

The most obvious Indian presence in medieval Europe was pepper, the quintessential Indian spice. Once known in Sanskrit sources as yavana-priya or ‘beloved by Romans’, pepper continued pouring into Mediterranean markets even after the fall of the empire. Historian Paul Freedman, in his paper ‘Spices and Late-Medieval European Ideas of Scarcity and Value’, demonstrates that medieval Europeans inherited the ancient Roman sense that pepper was precious and perilous. Medieval writer Isidore of Seville, drawing on classical authors Pliny and Solinus, claimed that pepper trees grew in India “guarded by poisonous serpents”. Harvesters, he wrote, had to burn the groves to drive the snakes away, which turned the originally white fruit black. The story ingeniously explained why pepper was shrivelled and dark (and made the spice all the more valuable in the process by saying it came from an Indian landscape of danger and marvels).

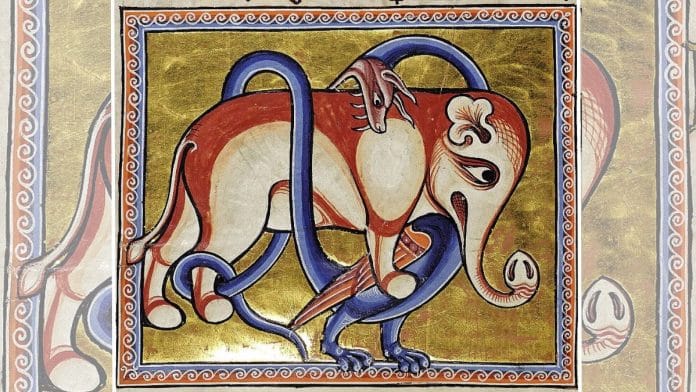

So, even as Indian goods—gems, textiles, spices, ivory—continued to be found in European wardrobes, sauces, and medicines, India itself took on an exotic, almost hallucinatory quality in the medieval European imagination. Roman-era writers—themselves relying on fragmentary and mistranslated ancient Greek authorities—had imagined the fringes of the world as home to species of dog-headed men (Cynocephali) and men with faces on their chests (Blemmyae). To Isidore of Seville, many of them were Indians. Yet even these strange, dangerous lands, it was believed, had received the Christian gospel, fitting the centrality of Biblical theology in the medieval European mind.

In a recent paper, historian Caitlin Green notes the Christian belief that St Thomas and St Bartholomew—two of Jesus’ own disciples—converted peoples in India’s deep South before being martyred and interred in churches. Today, Syrian Christians in Kerala claim direct descent from Brahmins converted by St Thomas. Though there is no contemporaneous evidence for this, by the seventh century CE, there is evidence that Malabar coast had a large Syrian Christian community.

The community’s connection to the Apostles inspired at least two obscure visits from medieval European travellers, studied by Green. The seventh-century bishop Gregory of Tours wrote of a certain Theodorus, possibly a Frankish or Gallo-Roman Christian, who visited and venerated an eternal lamp at St Thomas’ tomb in India. According to Green, this is possibly the same shrine in Mylapore, Chennai, that is revered today by Indian Christians as St Thomas’ resting place. Somewhat later, in the ninth century, Anglo-Saxon king Alfred the Great—having pulled off an unbelievable victory against Viking invaders—sent emissaries bearing gifts to Mylapore, the very edge of the world as imagined by European Christians. Throughout this period, the occasional Indian elephant, dispatched via Arab rulers or merchants, made its way around European courts to great fascination.

Legends of India only continued to grow over the centuries, especially when European Christendom clashed with the disunited Muslim world in the 12th century during the Crusades. Around this time, stories of a legendary Christian emperor called Prester John, ruling over the strange lands and peoples of distant India, entered the European imagination almost as if to balance the ever-too-real power of Muslim rulers such as Saladin.

India, in other words, was a place of wonder, sanctity, and wealth—a symbolic but positive Other that anchored Europe’s sense of the world.

Also read: Some OBCs were ‘dominant’ in medieval India. How history can decode the UGC controversy

Where were the Indians?

A recurring theme in Thinking Medieval has been that the world of a thousand years ago was borderless. In many earlier columns, we’ve examined Indian adventurers, merchants, monks, and mercenaries wandering inland Eurasia and island Southeast Asia. Why, then, were no Indians active in medieval Europe?

The simple answer is, they didn’t need to be. Ancient Roman mentions of Indians in, say, Italy were ‘embassies’ which made fabulous gifts to emperors. But these Indians, most likely merchants, were probably that far West because the centralised structure of the Roman Empire demanded and facilitated their presence. There were many more Indians in Roman Egypt doing business in Alexandria. Fragments of 11th-14th century Gujarati block prints found in Fustat, old Cairo, are evidence that Indians continued to live in Egypt for centuries after the fall of Rome. Also from Cairo come letters of medieval Jewish merchants, who mention Indian financiers and seafarers in Aden and other Red Sea ports around the same time. With reliable North African Jews and Arab Muslim business partners in the Mediterranean, and Europe itself composed of myriad decentralised polities and markets, there was little incentive for Indian merchants to risk an adventure there.

With all this said, it’s also important to point out a very different—and less powerful—group of ‘Indians’ in late medieval Europe. After a migration lasting several centuries, a people called the Roma appear suddenly in Balkan sources around the 1320s, and thereafter ever further West. Speaking an Indo-Aryan language from northern India, with influences from all the lands they had travelled—Persia, Armenia, Byzantium—they finally arrived in Europe in great trundling caravans. By the 1400s, they had arrived in Central Europe, occasionally presenting themselves as Christian pilgrims to avoid being accosted. These refugees and itinerant peoples are also a part of the story of Indians overseas.

The arrival of the Roma was a moment of incredible historical poignancy. For nearly a thousand years until this point, India lived in Europe as the positive Other—a memory, a marvel, a Christian possibility—but almost never as people. That long asymmetry finally broke when the Roma reached Europe. Yet within a single lifetime of that event, Vasco da Gama would step onto the Malabar coast, inaugurating a new, often violent, era of Indo-European contact. India would still be an exotic Other—but now dangerous, requiring European conquest, sanitation, and ‘upliftment’.

The India-Europe FTA is only the latest chapter in a relationship far older and more intricate than the colonial frame ever allowed. This column is a reminder, as always, that the ties binding India and its partners have always been richer, stranger, and more deeply entangled than the recent past would suggest.

This article is a part of the ‘Thinking Medieval‘ series that takes a deep dive into India’s medieval culture, politics, and history.

Anirudh Kanisetti is a public historian. He is the author of ‘Lords of Earth and Sea: A History of the Chola Empire’ and the award-winning ‘Lords of the Deccan’. He hosts the Echoes of India and Yuddha podcasts. He tweets @AKanisetti and is on Instagram @anirbuddha.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)