Who would have believed that a zamindar’s young widow could outwit the mighty British colonial government and make them eat humble pie? Not once, but twice!

Certainly, no one in mid-19th century Bengal would have ever entertained such an idea. Yet these unlikely occurrences did take place in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in the 1840s. Rani Rashmoni’s first act of defiance played out on the waters of the Hooghly.

Heroism on the Hooghly

The English East India Company, always on the lookout for fresh sources of revenue, imposed a tax on fishing boats operating on the Hooghly. It claimed that the river, which formed the western boundary of the city, was overcrowded with small watercraft that hampered the movement of larger ships and ferries. The fishermen were warned not to step into the water until they had paid the required amount and their nets were confiscated.

The river was the chief source of livelihood for the numerous fishing communities which dotted its banks. Such a tax would ruin them.

The fishermen approached several wealthy zamindars in the city for support, but none responded favourably, no doubt reluctant to offend the government top brass. They then made a last desperate appeal to Rani Rashmoni, the widow of zamindar Rajchandra Das, at the family mansion at Jaanbazar in central Kolkata. She reassured the fishermen that she would take care of the matter and set in motion her plan for retaliation.

From the government, she took out a lease on the stretch of the Hooghly between Ghusuri and Metiabruz, where the fishermen usually operated. It cost her 10,000 rupees, an astronomical amount at the time. As soon as the lease papers and payment receipt reached her, she issued certain instructions to Mathuramohan Biswas, her son-in-law and right-hand man in all business matters.

The next morning, all traffic on the river came to a grinding halt. Ships laden with cargo and passengers along the Hooghly found their path obstructed by a pair of immensely thick iron chains. One stretched across the river from bank to bank at Ghusuri and the other at Metiabruz, effectively blocking any vessel from plying in that particular expanse of water. With ships and ferries piling up behind the chains at each end, merchants and business houses began counting their losses as the hours ticked by.

Furious, the government demanded an explanation as to why she had done this. Her reply, sent through Mathuramohan, was curt. Since the government had granted the lease, that stretch of the river now belonged to her. The law gave her the right to do what she thought fit with it, and no explanations should be demanded. Turning their original argument on its head, she added that the constant movement of steamships disturbed the shoals of fish and made things difficult for the fishermen. Hence, she had cordoned off her portion of the river to protect their livelihood.

The Company’s officers were forced to concede defeat. They had no grounds to oppose her, as she had cleverly used their own laws against them. The government had to return the 10,000 rupees and give it in writing that the tax would be withdrawn and the fishermen could ply their trade in peace.

Durga Puja defiance

A similar conflict took place another year during Durga Puja, the most important festival in Bengal and one celebrated with great fanfare at the Rani’s mansion in Jaanbazar.

One of the rituals involved moving in procession at dawn to the ghat (flight of steps leading down to the river), accompanied by drums, cymbals, and bells. The noise awoke the soldiers sleeping in a nearby army barrack. Enraged at being disturbed, the colonel ordered his men to stop the cavalcade. Mathuramohan, who was leading the procession, explained that it was impossible to stop the ritual midway. The infuriated colonel fired into the air—and immediately found himself staring down the barrels of a dozen guns carried by the Rani’s guards, who had surrounded him. Realising they were completely outnumbered, the soldiers were forced to step back and allow the procession to continue.

The issue soon snowballed into a legal battle. Rani Rashmoni submitted documents proving that the street down which the procession had travelled—and on which her mansion stood—belonged to her. Incidentally, it was named Babu Road, leading to Babughat, after her deceased husband Rajchandra Das. The deed was valid, carrying the signature of the garrison officer of the area in question. To prevent a complete loss of face for the Company’s government, the court ordered her to pay a fine of 50 rupees.

Rani Rashmoni was not one to back down without a fight. She paid the fine, but that very day she ordered thick wooden poles to be placed at intervals along the road from the mansion to the ghat. Ropes then cordoned off the entire stretch, preventing entry onto the road from any of the connecting streets. Traffic in the area, one of the busiest in Calcutta, came to a standstill.

The government issued strict orders that the road be opened immediately. Rashmoni replied that since she owned the road, the government would have to pay the requisite amount for using it. Once again, she had outwitted them—the government could hardly deny the validity of a document signed by their own garrison officer. The fine was returned and a written appeal sent to her to relent and open the road.

However, the government had learnt its lesson and had no desire to get its fingers burnt again. A new law was passed requiring anyone taking out a procession on the streets of Calcutta to obtain a pass or written permission from the authorities.

Also Read: A Bengali feminist from 1800s, critic of British rule who couldn’t stop child marriage at home

A woman ahead of her time

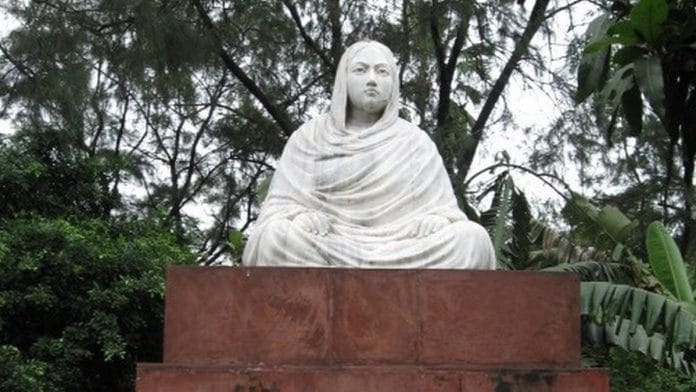

Rani Rashmoni (1793–1861) is best known for establishing the Dakshineshwar Kali Temple near Kolkata, and for her association with Sri Ramakrishna Paramhansa—the saint and head priest of the temple, whom Swami Vivekananda acknowledged as his Guru.

Here too, she faced obstacles—no priest was willing to consecrate the temple and initiate the rituals, arguing that Rashmoni, as a Shudra woman, had no right to own a temple or offer food to Brahmins. Ultimately, the problem was resolved by transferring ownership of the entire temple property to the family priest. However, Rashmoni insisted that the temple be open to persons of all castes and religions, and so it remains to this day.

She remains a beloved figure in Bengal for her courage, judgement, and generosity, channelling her wealth into innumerable charitable works. These ranged from constructing a road from the Subarnarekha river to Puri for the benefit of pilgrims, to building a series of ghats along the Hooghly, to large donations to the Imperial Library (now the National Library) and Hindu College (now Presidency University).

The ‘Rani’ in her name did not refer to royal status. It was an honorific given by the ordinary, downtrodden masses who loved her. She was a rarity—a woman who combined razor-sharp business acumen with a compassionate heart, ever ready to help those in distress. A woman far ahead of her times, she took on entrenched powers, both social and political, relying on her own wits and indomitable courage, and left behind a rich legacy.

Note: All information in this article has been sourced from two Bengali books: Rajeshwari Rani Rashmoni by Gourangaprasad Ghosh (Jogmaya Prokashoni, December 1960, pp. 195–201, 213–217, 266–269), and Rani Rashmoni by Prabodh Chandra Santra (Narendranath Das, 1913, pp. 43–44, 58–59).

Dr Krishnokoli Hazra teaches history at the undergraduate level in Kolkata. Views are personal.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Splendid. The way Dr. Hazra has portrayed the narrative in English brings out the character of ‘Lokmata’ Rasmoni in a strikingly dramatic manner.