At 9 am on a hot September day, an 18-year-old young woman, dressed in the European style, stepped down from the train onto the platform in Bombay, now Mumbai, in 1882. The station was crowded and people were milling about everywhere.

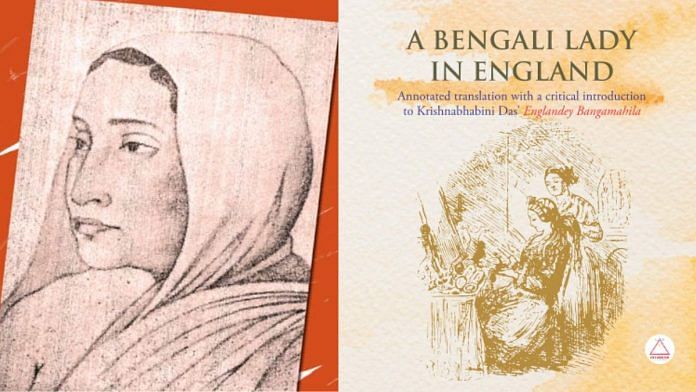

Krishnabhabini Das, a Bengali travel writer who chronicled life in England, was an early feminist who broke many taboos. But more importantly, she often offered one of the harshest and most comprehensive condemnations of colonial rule almost 140 years ago in her book titled Englandey Bangamahila (A Bengali Lady in England). Unsurprisingly, it was banned by the British government in India.

“[Englishmen] believe that all the countries of this world and its inhabitants have been created just to fulfil their wishes and satiate their desires,” she wrote back then. “They are intolerant when others demand their logical share…A far-flung empire and acquired wealth have made them excessively proud. They believe the entire world is beneath their feet and all the nations of the world are inferior to them…. There is probably no country from which they are not sucking out money.”

There was plenty that she admired too about English ways.

As she waited for the porters to unload the luggage at the railway station while her husband went to look for a taxi, she was pleasantly surprised that a lone woman did not attract too many stares. “If I stood here with a veil over my head, I would have become the target of everyone’s gaze, but such was the greatness of English clothing that no one dared to look at me. In fact, they seemed afraid to do so,” she mused.

Krishnabhabini Das wrote the first full length account of travels and residence in the West by a Bengali lady. Her comment simultaneously highlighted the potential of clothing to be the vehicle for feminine independence and critiqued the instinctive deference of the colonised male towards perceived ‘Englishness.’ It was only one of her many insightful observations.

Also read: Mahasweta Devi–the crusader, activist, writer who fought for the oppressed

Travelling to England

Born in 1864 in a village of Murshidabad district in today’s West Bengal, Krishnabhabini was married off at the age of nine to Debendranath Das, son of a wealthy lawyer of north Kolkata. Debendranath left for England to return after six years with a degree from the University of Cambridge. On his return, his orthodox father disowned him as crossing the seas was considered an absolute taboo in traditional Hindu society at the time. Ostracised by family and friends, Debendranath decided to return to England in 1882. Despite family opposition, Krishnabhabini accompanied him. Her in-laws compelled her to leave behind her five-year-old daughter. Eight years were to pass before they could return.

Having qualified at the University of Cambridge, Debendranath took up teaching and ensured his wife’s education as well. In 1885, Englondey Bangamahila was published in Calcutta (now Kolkata) under the pseudonym, Bangamahila (A Bengali woman).

Education is the key

Nabanita Sengupta, author of an annotated English translation of the book, notes that Krishnabhabini’s account was an incisive social commentary of diverse aspects of life in Britain. What struck her most was the sharp contrast in the lives of women in Britain with those in India.

One of the first things that amazed her was that in England, most women had access to education. Noting that there was no dearth of women with BA or MA degrees in London, she lamented that the ‘daughters of India’ were ‘totally illiterate’ and ‘uneducated in the fine arts.’

In her opinion, this conclusively proved that women were not inferior to men, indeed, they were equal, since they had to overcome many more obstacles than the latter. “I cannot express the delight I feel in my heart when I see groups of girls going to school like boys and young women going to college like the young men,” she exclaimed. Coming from a society where educating girls was believed to cause widowhood, her joy is easily understood.

The importance given by English schools to physical fitness for girls where they played outdoors and excelled in ‘men’s sports’ won her approbation. She wrote wryly that many of the women, skilled in horse-riding, lawn tennis and athletics were mentally and physically stronger than most Indian men.

Contrasting England and India

Krishnabhabini was particularly perceptive in her observations of the English household. She emphasised that its main difference with the typical Indian household was that there was no segregation between the ‘outer’ (male) and ‘inner’ (female) sections. The lady of the house looked after the entire house and even entertained guests. In Krishnabhabini’s eyes the man may be the head of the English household but the woman was ‘literally the queen.’

She was contemptuous of the rich, idle women of the British aristocracy but did not waste many words on them, commenting only that such wealthy, indolent ladies were to be found in ‘every country.’ Her deepest admiration was aroused by the women who did ‘men’s work’ as efficiently as men—the women who, in addition to managing a household, ran shops, worked as clerks, taught in schools and wrote books and articles in newspapers.

Although raised in a conservative milieu, Krishnabhabini was sceptical of social norms which made a woman’s happiness and entire well-being dependent on the caprice of her fiancé or husband.

Prof. Simonti Sen, in her book Travels to Europe: Self and Other in Bengali Travel Narratives,1870-1910, has shown how Krishnabhabini stood out from contemporary Bengali male travelogue writers. Krishnabhabini approved of how English law provided legal redressal for engaged women facing a ‘breach of promise’ by their betrothed and for wives with adulterous husbands.

‘Suffer in silence’ was not her motto.

Her impassioned plea, “If we can, like Englishwomen who are struggling to get women members elected to Parliament, shout for our demands, if we can cease to call ourselves feeble and modest and strike at the heart of every Indian, perhaps only then our men will wake up to our misery,” resonates even today.

Also read: Jailed at 13, S N Subbarao went on to rehabilitate 600 dacoits in Chambal valley

Shackled women, Enslaved nation

Prof. Jayati Gupta, author of Travel Culture, Travel Writing and Bengali Women, 1870-1940, states that in early 20th century India, the idea of female emancipation was deeply embedded in the idea of freeing an enslaved nation. Krishnabhabini was among the earliest Indian women with exposure to the West, to articulate this.

“According to me they [Englishwomen] are really the other half of men. The way women here usually help men with their work or…do men’s work is never seen in our country. They perform the ‘male jobs’ very efficiently. Women form half the country’s population and if they stay idle or do very little work, the entire nation is harmed,” she wrote.

Her accompanying lament that this was not the case in her country, may be read as a strong feminist critique of colonialism—a nation which kept half its population ignorant and shackled by custom and superstition and became weak and laid itself open to subjugation by another.

But for all her empowering writing, Krishnabhabini Das could not prevent her daughter’s marriage at the age of 10, to an adulterous man. Her daughter was deeply unhappy and died at 30.

When Krishnabhabini’s husband died shortly after, she even wore white and travelled bare feet from house to house asking families to send their daughters to schools. Her modest attire gained her entry into the inner quarters of homes. She also supervised a branch of Bharat Stree Mahamandal in Kolkata, a school for girls. Author of many articles on women’s education in journals of the time, she devoted the rest of her life to helping other oppressed women.

Dr Krishnokoli Hazra teaches History at the undergraduate level in Kolkata.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)