Everyone these days is talking about tariffs. India has been accused of being a tariff king, suggesting that the country keeps its tariffs high. The United States President Donald Trump has levied additional tariffs of over 50 per cent on imports of most goods from India. Indian exporters are, obviously, worried and concerned.

But this piece is not about whether India’s tariffs are high. Nor is it about assessing the seriousness of the impact of higher tariffs on Indian exports. Instead, an attempt is being made here to evaluate the impact of tariffs on the exchequer by way of tax revenue. One of the reasons behind Mr Trump’s move to raise tariffs is to bolster his government’s revenue flow. So, how have India’s tariffs played out with regard to its own tax revenue?

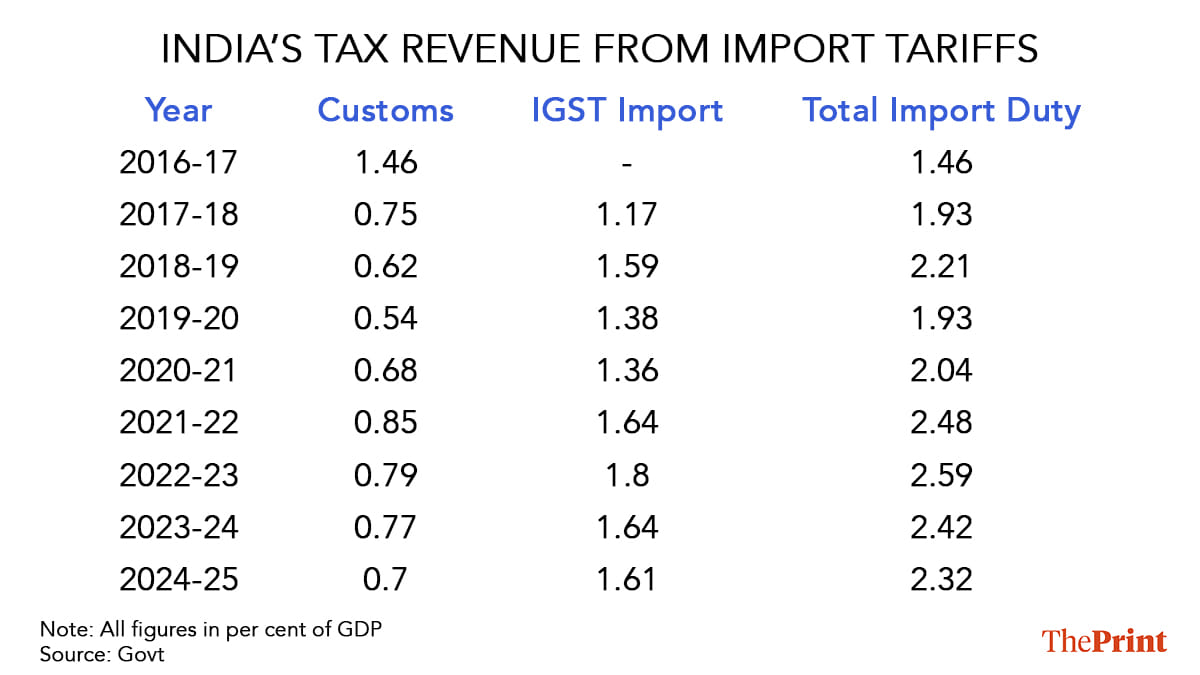

The last decade or so provides a nice base for studying the trends in government revenue from import tariffs of all types. This is because, during this period, the instrumentality of levying taxes on imported goods and services underwent a significant change.

Till June 30, 2017, Customs duty provided a comprehensive picture of the total tax revenue collected by the Union government through various forms of import duties. With the launch of goods and services tax (GST) from July 2017, this was no longer true. Taxes such as countervailing duty levied on imports were subsumed in the GST structure, which had three segments — Central GST, State GST and Integrated GST or IGST.

There are two components of IGST — it is levied on all inter-state transactions of taxable goods and services and on imports. The IGST rate is mostly 18 per cent on all such inter-state transactions and imports. The revenue from IGST is shared by the Centre and the states, depending on the final destination of the goods and services. Thus, after the launch of the GST regime, a complete picture of India’s tax revenue from import tariffs is available only if you take into account collections of both Customs duty and IGST on imports.

In 2016-17, the last full financial year before GST was launched, the Union government’s Customs duty collections were about ~2.25 trillion. This amount was equivalent to 1.5 per cent of India’s nominal gross domestic product (GDP) and 8.7 per cent of its total goods imports that year. Customs duty collections last financial year, almost eight years later, were almost unchanged at ~2.33 trillion or sharply down at 0.7 per cent of GDP. In tune with that fall, Customs duty collections accounted for only 3.8 per cent of India’s merchandise goods imports in 2024-25.

Note that in the post-GST era, Customs duty collections have ceased to be the only indicator of India’s import tariffs. IGST on imports has begun to play a significant role in boosting India’s tax revenue from imports. Gross IGST on imports rose from ~3 trillion in 2018-19 (the first full year after the launch of the GST regime) to ~5.33 trillion in 2024-25. Interestingly, the Covid pandemic did not have any major impact on collections from import duties — neither on Customs nor on IGST on imports, contrary to the sharp setback in collections of other taxes in 2020-21.

No surprise that the combined collections from Customs and IGST on imports almost doubled from ~4.18 trillion in 2018-19 to ~7.66 trillion in 2024-25. But as percentage of GDP and total imports of goods and services in this period, the combined collections of Customs and IGST on imports rose only marginally — from 2.21 per cent to 2.32 per cent of GDP, and from 9.34 per cent to 9.91 per cent of total goods and services imports.

A change in the composition of revenue from import duties, however, was clearly noticeable. The share of Customs in total import tariff collections fell significantly over the last eight years since the launch of the GST regime. What kept the import duty collections growth momentum somewhat intact was the rise in IGST on imports, which shot up from ~3 trillion in 2018-19 to ~5.33 trillion in 2024-25. Of course, the net IGST on imports was a little lower because of export refunds of about a fifth of total collections. But the larger point about a sharp rise in IGST on imports cannot be missed. Indeed, since the new taxation regime’s launch in July 2017, IGST on imports has consistently maintained a share of a fourth of total annual GST collections.

Also read: US bullying spurred Green Revolution. Let tariffs give us a Business Revolution

For the Centre, however, the changing composition of the total import duty collections has dented its net tax revenue in light of the devolution formula recommended by the Finance Commission. The Centre has had to share about 41-42 per cent of the Customs duty collections with states in this period. But the IGST collections on imports have to be shared with the states at a rate that is much higher. About half of the IGST on imports is shared with the states. The remaining half comes to the Centre, but even this amount is shared with the states as per the Finance Commission-mandated formula of 41-42 per cent.

What emerges clearly from these numbers is that the IGST component of total import duty collections is growing faster than that from Customs duty. But states enjoy an effectively larger share in the rapidly growing pie of IGST on imports because of the manner in which these duties are shared. The Centre may take the blame for maintaining a tariff regime that exporters to India might complain. But the revenue gains from such a tariff regime are more for the states. For the Centre, this may be a fiscally benevolent and generous approach towards the states. But the Centre may not remain very pleased for long with a situation where the states end up getting a much larger share of the total duties collected on imports of goods and services.

Once the 14th and 15th Finance Commissions raised the share of central taxes to be transferred to the states to 42 per cent and 41 per cent, respectively, the Centre over the last decade or so has increased its reliance on cesses and surcharges, which are not part of the divisible pool, and prevented a larger transfer of taxes. Will the Centre do something similar to limit the states’ import revenue share?

AK Bhattacharya is the Editorial Director, Business Standard. He tweets @AshokAkaybee. Views are personal.