I would like to refer to what Shri Hiren Mukerjee said the other day. He charged me with a number of things. He suggested that I had deviated from Pandit Nehru’s policies. If he will permit me to say so, it should not be difficult for a professor to know the correct position. But since he happens to be a Communist, it is difficult for him to think outside the framework of the Communist idea. May I tell him that in a democracy, there is nothing like deviation or deviationist? It does not find a place in the dictionary of a democracy. In a democracy, there is every opportunity for re-thinking and freedom for the formation of new schemes and policies.

I said on the very first day of my election, and on more than one occasion later, that the Government of India will continue to follow the policy of Nehruji in international matters and democratic socialism will continue to be our objective in our domestic policy. In spite of that, Shri Hiren Mukerjee has made so much criticism of what he thinks I have done or propose to do. I would not have said all these things, or what I want to say now, but it is time that I might make it quite clear as to what my attitude is in regard to this particular objection raised by Shri Hiren Mukerjee. Otherwise, every time, quite frequently, either Shri Hiren Mukerjee or his colleagues will get up and say that I am deviating and start censuring.

May I repeat that in a democracy, there is full freedom for rethinking and independent thinking? May I also remind him of what happened during our freedom struggle days? I know it personally, at least for the last 40 or 42 years. What happened when Mahatma Gandhi took over the leadership? There was a complete overhaul, complete change in philosophy, policy, technique and programmes. Mahatma Gandhi completely deviated: from Lok Manya Tilak, Aurobindo Ghosh and Lala Lajpat Rai.

Shri Hem Barua: Please do not use the word “deviated”.

Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri: I am sorry. I quite agree with him. I am using it for the benefit of Professor Mukerjee; he might be able to understand it better. Till then, the policy was that there should be tit for tat. Lok Manya Tilak went to the extent of suggesting that he would be agreeable to responsive co-operation. Shri Aurobindo and many of his other followers felt that there was no alternative but to resort to arms and use ‘weapons and arms in order to fight the British Government or authorities. Then comes Mahatma Gandhi. He completely disagrees with them and adopts a new philosophy and a new technique. Will you condemn Gandhiji for this? I hope Professor Mukerjee will be good enough at least to excuse Gandhiji, if not me?

And may I say what happened in the case of Shri Jawaharlal Nehru himself? In a way, Gandhiji was the preceptor of Jawaharlalji, guru in a sense, because Jawaharlalji was not taking part in politics in all seriousness in the Home Rule days; he took seriously to politics when Gandhiji came into the field, because he felt that here was a man who believed in revolution, who believed in change, and who believed in action. So, he was attracted towards Gandhiji. But did he entirely agree with Gandhiji? No. And yet could you find a more loyal and devoted person to Gandhiji than Jawaharlalji? I say, he loved Gandhiji immensely and he gave his fullest loyalty to Gandhiji; yet, he had his own way of thinking, independent way of thinking.

Although he did not believe in non-violence, yet when he found the way Gandhiji worked it and the success he achieved, he said “I am a complete convert to non-violence and non-violent techniques”. Of course, it did not mean that he accepted non-violence as a creed. He didn’t. And yet when Gandhiji said ‘if you want to achieve ‘good ends, you must adopt good means also”, it attracted Jawaharlalji most. I rememember that because he talked to us about it and he also made public statements. If possible, I shall refer to a part of his speech which he delivered at the banquet given to Mr. Khrushchev and Mr. Bulganin where he said that he believed in good means. Therefore, without fully agreeing with Gandhiji, he had his own way of thinking and approach.

He was a man who stood for peace and non-violence. In the ‘message of non-violence he saw a picture of peace in the whole world. In his mind he felt “here is a man who is preaching non-violence.” Of course, his idea of its application was not restricted to India. Gandhiji had said “if you succeed in India, this message will spread throughout the world”. But Nehruji had an international approach. So he, in his own way, took non-violence to the world platform, to the world forum and in a practical way preached disarmament, worked for it, and did his best to make various proposals so that disarmament may be successful. He saved many wars, or a few wars, by what he did to maintain peace in the world. When he joined the government, it was not possible for him to put into effect each and every idea of Gandhiji. But this does not mean that he was, in any way, disloyal to Gandhiji or he did not do what was right.

Why restrict ourselves to India? What is happening or what has happened in Russia? What did Lenin do? When the first Communist government was formed, Lenin tried to put into effect fully all the policies enunciated by Marx in Das Kapital—free kitchens, free travelling, free stamps; everything was almost free. Everybody could go and take his food from the government kitchen. Then, there were several programmes of nationalisation etc. What happened? Lenin found after some time that it was impossible to work some of them. So, he announced a new economic policy (NEP) and it was put into effect. It was a departure from what Marx had actually said in his book.

Now, Lenin goes and Stalin comes. What does he do? I need not tell the House—every one of you is aware—as to what Stalin did. In fact, he was totally different from Lenin. I consider Lenin to be one of the biggest revolutionaries of the world. But if I might say—I hope, I would be excused—I consider Stalin not to be a revolutionary at all. Whether one agrees with it or not is a different matter, but Stalin used the government machine for continuing his reign over the Soviet land until he lived. For him, it was just a struggle for power throughout his life.

Now, let us consider the policy Premier Khrushchev is pursuing. He has censured Stalin—and his policies also—in the strongest terms possible. The basic ideology is wholly acceptable to Premier Khrushchev—in fact, he is the greatest exponent of this theory in the modern times—but he has flatly refused to tread the beaten track and has adopted a new programme and technique.

I need not refer to Mao Tse-tung, who is another important figure in the Communist world and whose ways of doing things are known, or perhaps well-known.

As I said, I consider Premier Khrushchev to be one of the most important distinguished leaders of the world. I say so because he refuses to walk on the beaten track. A leader generally, if he is really the leader, does not walk on beaten tracks because in the political field, situations change, men change, conditions change, environments change, and the real leader must give the reply to the changing conditions.

We do not want to drag in the name of Pandit Jawaharlalji for covering our lapses and inefficiencies. We will never do that. We must own the entire responsibility for what we do. But we cannot forget our great leader, Pandit Jawaharlalji, our Prime Minister, our hero with whom we worked for 40 years, for about half a century. We can never forget him; we will ever remember him and we will try to follow in his footsteps in the best manner possible.

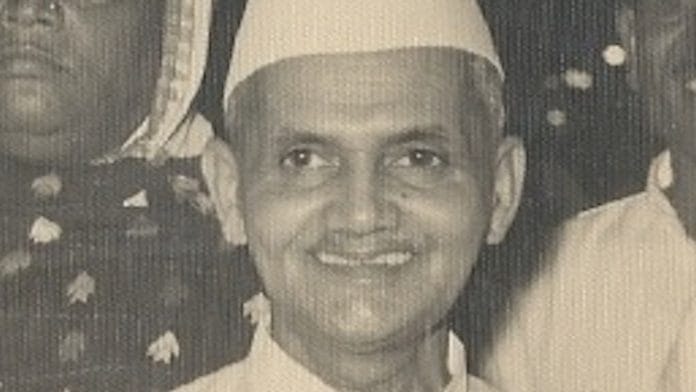

Editor’s note: This is an abridged version of Lal Bahadur Shastri’s Lok Sabha speech, delivered during a no-confidence motion against his government on 18 September 1964. Read the full speech here.

This is part of ThePrint’s Great Speeches series. It features speeches and debates that shaped modern India.