When we brought forward these amendments, any desire to curb or restrain the freedom of the Press, generally speaking, was exceedingly far from our minds. That, of course, is no excuse, or no reason, if in effect the words do that—I realise that—and it is folly for any Government to say, “We did not think of this”, when a certain consequence inevitably flowed from that action. That is perfectly true. Nevertheless, there is something in it when I repeat that any desire to curb the freedom of the Press was not before us.

We are dealing with a particular situation, I think a difficult situation, a situation which grows more difficult for a variety of reasons, national and international. And it was not in terms of curbing the Press but it was rather in wider terms that we thought of this problem. Because we were all the time considering the question of the Press rather independently, we wanted to deal with it independently, to put an end to some old laws and bring something more in conformity with modern practice, in consultation with those people who are concerned with this matter.

However, it is perfectly true that whether we thought of it or not, this affects the situation to some extent. It affects it in two ways: one, directly—that is to say a certain thing has been done which may put an obstruction in the way of the Press in theory, and, secondly, it may give a chance to a Government to impose some disabilities, that is, the Government may have the legal power to impose some disabilities unless some change is made. Both are possibilities, I recognise that.

So far as we are concerned we do not wish, and we do not wish any State Government, to take unfair advantage or any advantage of this change to curb the freedom of the Press, generally speaking, and we wish to review the whole scheme as soon as possible. But I would beg of you to consider this matter in theory as well as of course in practice.

Great exception has been taken to some additional phrases in the proposed Article 19(2). First of all, may I draw your attention to a major change; although the change is of one word only, it is a major change. That is the introduction of the word “reasonable” which makes anything done patently justiciable, although, as a matter of fact, even the word “reasonable” was not there every part of the Constitution, within some limitations, is always justiciable. It just did not matter if this word “reasonable” was there or not—the matter could have gone to a court of law and could have been interpreted by our superior courts. There is no doubt about that.

It is true that their interpretation would have been limited by the new thing that we have said. That is true, of course, because in interpreting the Constitution they will have to consider the new part of the Constitution that has come in. Nevertheless, the interpretation would have been given taking the Constitution as a whole—the spirit of it, the wording of it, the precise language of it, and so on and so forth. Nothing can take away their power to consider any part of the Constitution and to give their opinion. You can, by constitutional amendments, direct your attention one way, that the Constitution means this more than the other, and naturally they would interpret it a little that way. But then, whether the word “reasonable” is there or not, surely it is open to a court, if some fantastic thing was done, to say it is fantastic.

Suppose the word “reasonable” was absent from all those various clauses of Article 19 as it does occur in various clauses, it does not mean that the idea of “reasonable” was absent. It is there although the word may be absent. However, I shall not go into that technical argument. My point is that whatever the power the court might have had if the word “reasonable” had not been there, certainly the introduction of the word “reasonable” gives it the direct authority to consider this matter.

Now why did we not put that word “reasonable” at an early stage? Then we wished to avoid not so much the courts coming into the picture to give their interpretation; not that, but we wished to avoid an excess of litigation about every matter, everything being held up and hundreds, and may be thousands, of references constantly made by odd individuals or odd groups, thereby holding up not only the working of the State but producing a mental confusion in people’s minds at a time when such confusion might do grave injury to the State.

***

Now, the Press has said a great deal about the liberty of the Press. I know something of the Press, and I have been connected with the Press too somewhat, and I can understand their apprehensions. Yet I say that what they have said is entirely unfair to this Government. And I say that the Press, if it wants that freedom—which it ought to have—must also have some balance of mind which it seldom possesses. They cannot have it both ways—no balance and freedom.

Every freedom in this world is limited, limited not by law so much, limited by circumstances. We do not wish to come in their way. Personally, I am convinced, as I have said previously, and as I believe a pamphlet has been circulated which contains the speech of mine delivered some time back—I am glad that it has been circulated, because I repeat I stand by every word of what I have said about the freedom of the Press—and I hope that in so far as I can I shall be able to help in maintaining that freedom. That is so.

But I care a little more for the freedom of India, and I am not going to allow anything coming in the way of the freedom and unity of India, whatever it may be. I do not mean to say that the freedom of the Press comes in the way of the freedom of India. Not that. But we have to look at things in the proper perspective and not lose ourselves as if we are in a court of law, arguing this case or that case. We are legislators sitting in Parliament with the fate of this nation in our hands, possibly also affecting to some extent the fate of other nations. It is a difficult and highly responsible position, and we cannot be moved away by passion or prejudice or by some logical chain of thought which has no relation to reality.

Therefore we have to consider these matters in all seriousness, remembering always that certain freedoms have to be preserved. It is dangerous even in the flush of excitement to weaken them. I admit. We must not weaken them. At the same time, while we want freedom, freedom of the Press or freedom of speech or freedom of anything—they may be good—we have to remember that the nation must be free, the individual must be free and the country must be free. If national freedom is imperilled or individual freedom is imperilled, what good do other freedoms do? Because the basis of freedom is gone. So all these have to be balanced. Maybe the balance we suggest is not a correct balance. Let us look at it. But it is no good saying vaguely that this freedom has been attacked and weakened.

The House will remember—a fact that has been repeatedly stated—that this amendment is an enabling one, it is not a law. If there was a law before the House it should be considered very carefully, each word. Naturally when you give an enabling power, it is given in slightly wider terms. Suppose I say “friendly relations with foreign Governments”, it is a friendly way of putting it; it is a nice way of putting it, both from the literary point of view and from the international or national point of view.

Exactly what would amount to a danger to friendly relations is so difficult to state; you cannot specify. You may, of course, put down one thing or the other. You may say “defamatory attacks” as we sought to say at one time “defamatory attacks on the heads of foreign nations or others” but in effect if once you have a check to see that it is not done unreasonably, it is best you use gentle language.

During three years or so, and long before the courts gave this clause this interpretation, I am not aware it may be—I am wrong—of any action being taken anywhere in regard to criticism of foreign countries or foreign policy. So far as I am concerned and so long as I have anything to do with it, I can assure you that you can criticise to your heart’s limit and extent the foreign policy that my Government pursues or the policy of any country; to the utmost limit you can go. I do not dislike your criticism; nobody will be allowed to come in their way. But suppose you do something which seems to us to incite to war, do you think we ought to remain quiet and await the war to come? And if it is so, I am sure no country would do that. We cannot imperil the safety of the whole nation in the name of some fancied freedom which puts an end to all freedom.

Therefore, it is not a question of stopping the freedom of criticism of any country and naturally we should like not to indulge in what might be called defamatory attacks against leading foreign personalities. That is never good, but in regard to any policy you can criticise it to the utmost limit that you like, either our policy or any country’s policy; but always thinking in terms of this, that we are living in a very delicate state of affairs in this world, when words, whether oral or written, count; they make a difference for the good or for the bad. A bad word said out of place may create a grave situation, as it often does. In fact, it would be a good thing, I think, if many statesmen, most of them are all dealing with foreign affairs, became quiet for a few months; it would be a still better thing if newspapers became quiet for a few months. It would be best of all if all were quiet for a few months. However, these are pious aspirations which I fear will not be accepted or acted up to but we live in dangerous times and I wish the House to consider them in dealing with this Article 19(2).

In the Select Committee, we examined it in a variety of ways. You will remember that the word “reasonable” was not there at first. We tried to redraft it completely, more on the lines of the present shape of words in Article 19(2) of the Constitution. In the present form of words, there is no mention of “restrictions”. So we thought that we had better proceed on that line and then we tried naturally to limit the various subjects mentioned there, for instance—I should be quite frank with you—in regard to friendly relations with foreign powers, we sought to put in the words “defamatory attacks on heads of foreign States” plus such other attacks which might impair the friendly relations with foreign States.

Now that is obviously limited and that is all that one wants and so we went on limiting the other subjects. We produced a new draft at that time. Then we looked at it and we found that while some people liked this part of the draft better, the other people liked that, but nobody seemed to like the whole thing as it was and so we thought: Let us go back to our old draft but with a very major change, that is, the addition of the word “reasonable” which really, immediately and explicitly limits everything that you do and puts it for the courts to determine whether it is reasonable or not. It is a big addition. As I said, it is not the courts we are afraid of. There are courts of eminent judges, but what really frightens me a little is the tremendous volume and bulk of litigation that all this kind of thing encourages and thereby bringing in complete uncertainty in everything.

There is one thing else. My colleague Shrimati Durgabai has put in a note in which she has argued that these changes should be made by Parliament and not by the States. I am 100 per cent. in sympathy with her desire. My sympathies are there but my mind is not quite clear about the legal aspects of this.

I think it would be a very good thing if Parliament alone can go into these matters, but I am assured by some lawyers that there are difficulties in the way. Then again another Member of the Select Committee has suggested that the President may certify any such Bills connected with these matters passed by the State Legislatures. That is a matter which we may consider. These are not matters of basic principles because we do want two things: A certain power to deal with a certain critical situation if and when it arises and we do want checks to see that that power may not be misused. We want both these things.

It is impossible to do these things perfectly; you have to find some middle way and trust to luck that the people who exercise that power will be sensible, reasonable and wise. As a matter of fact, Governments, whether Central or State Governments today have naturally a great deal of power. If they misuse it they can do a lot of mischief in a hundred and other ways. Ultimately the check consists in that Government falling out. The only check is that we have to choose the right persons who are likely to behave in a reasonable and wise way.

I need not draw your attention to the fact that not only the word “reasonable” has gone in in Article 19 but two or three lines of words have gone in, which I think improve the Article greatly and make it more concise and bring the whole scope of the Article under the word “reasonable”.

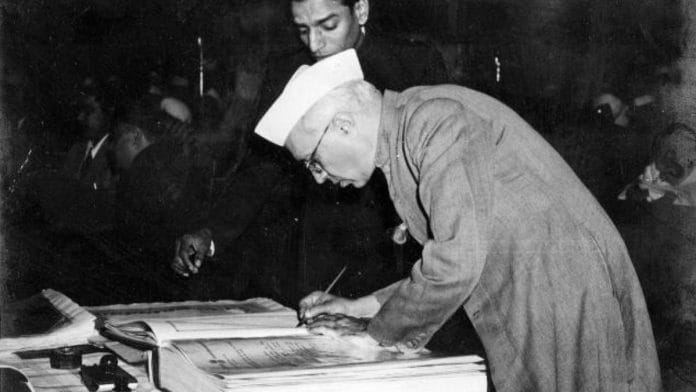

This is part of ThePrint’s Great Speeches series. It features speeches and debates that shaped modern India.