I wrote some years ago a Marathi pamphlet exposing the religious practices of the Brahmins and incidentally among other matters, adverted therein to the present: system of education, which by providing ampler funds for higher education tended to educate Brahmins and the higher classes only, and to leave the masses wallowing in ignorance and poverty. I summarised the views expressed in the book in an English preface attached thereto, portions of which I reproduce here so far as they relate to the present enquiry:

“Perhaps a part of the blame in bringing matters to this crisis maybe justly laid to the credit of the Government. Whatever may have been their motives in providing ampler funds and greater facilities for higher education, and neglecting that of the masses, it will be acknowledged by all that injustice to the latter, this is not as it should be. It is an admitted fact that the greater portion of the revenues of the Indian Empire are derived from the ryot [peasant farmer]’s labour from the sweat of his brow. The higher and richer classes contribute little or nothing to the state exchequer. A well informed English writer states that our income is derived, not from surplus profits, but from capital; not from luxuries, but from the poorest necessaries. It is the product of sin and tears.”

That Government should expend profusely a large portion of revenue thus raised, on the education of the higher classes, for it is these only who take advantage of it, is anything but just or equitable. Their object in patronising this actual high class education appears to be to prepare scholars who, it is thought would in time vend learning without money and without price. If we can inspire, say they, the love of knowledge in the minds of the superior classes, the result will be a higher standard, of morals in the cases of the individuals, a large amount of affection for the British Government, and unconquerable desire to spread among their own countrymen the intellectual blessings which they have received.

Regarding these objects of Government the writer above alluded to, states that we have never heard of’ philosophy more benevolent and more utopion. It is proposed by men who witness the wondrous changes brought about in the Western world, purely by the agency of popular knowledge, to redress the defects of the two hundred millions of India, by giving superior education to the superior classes and to them only. We ask the friends of Indian Universities to favour us with a single example of the truth of their theory from, the instances which have already fallen within the scope of their experience. They have educated many children of wealthy men and have been the means of advancing very materially the worldly prospects of some of their pupils. But what contribution have these made to great work of regenerating their fellowmen? How have they begun to act upon the masses? Have any of them formed classes at, their own homes or elsewhere, for the instruction of their less fortunate or less wise countrymen?

Or have they kept their knowledge to themselves, as a personal gift, not to be soiled by contact with the ignorant vulgar? Have they in any way shown, themselves anxious to advance the general interests and repay the philanthropy with patriotism? Upon what grounds is it asserted that the best way to advance the moral and intellectual welfare of the people is to raise the standard of instruction among the higher classes? A glorious arguments this for aristocracy, were it only tenable. To show the growth of the national happiness, it would only be necessary to refer to the number of pupils at the colleges and the lists of’ academic degrees. Each wrangler would be accounted a national benefactor; and the existence of Deans and Proctors would be associated, like the game laws and the ten-pound franchise, with the best interests of the constitution.”

One of the most glaring tendencies of Government system of’ high class education has been the virtual monopoly of all the higher offices under them by Brahmins. If the welfare of the Ryot is at heart, if it is the duty of Government to check a host of abuses, it behoves them to narrow this monopoly day by day so as to allow a sprinkling of the other castes, to get into the public services. Perhaps some might be inclined to say that it is not feasible in the present state of education. Our only reply is that if Government look a little less after higher education which is able to take care of itself and more towards the education of the masses there would be no difficulty in training up a body of men every way qualified and perhaps far better in morals and manners.”

My object in writing the present volume is not only to tell my Shudra brethren how they have been duped by the Brahmins, but also to open the eyes of Government to that pernicious system of high class education, which has hitherto been so persistently followed, and which statesmen like Sir George Campbell, the present Lieutenant Governor of Bengal, with broad universal sympathies, are finding to be highly mischievous and pernicious to the interests of Government. I sincerely hope that Government will ere long see the error of their ways, trust less to writers or men who look through highclass spectacles, and take the glory into their own hands of emancipating my Shudra brethren from the trammels of bondage which the Brahmins have woven around them like the coils of a serpent.

It is no less the duty of each of my Shudra brethren as have received any education, to place before Government the true state of their fellowmen and endeavour to the best of their power to emancipate themselves from Brahmin thraldom. Let there be schools for the Shudras in every village; but away with all Brahmin school-masters! The Shudras are the life and sinews of the country, and it is to them alone, and not to the Brahmins, that Government must ever look to tide over their difficulties, financial as well as political. If the hearts and minds of the Shudras are made happy and content, the British Government need have no fear for their loyalty in the future.”

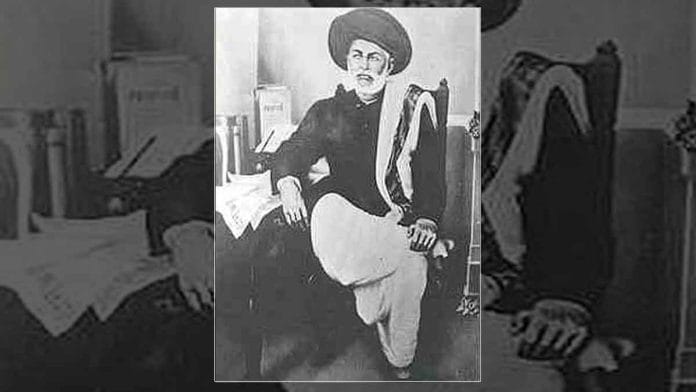

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from Jyotirao Phule’s deposition before the Hunter Commission in 1881. Read the full speech here.

This is part of ThePrint’s Great Speeches series. It features speeches and debates that shaped modern India.

And Brahmin Jawaharlal Nehru continued the same pernicious practice by completely neglecting primary education, whilst pursuing his obsession of IITs, IIMs, national science labs divorced from day to day education of the masses. All his efforts created a bunch of literate coolies to serve the West.