The stations south of Medain Salih are fortified with trenches and barbed wire,” the traveller Ali bin Muhammed recorded in his diary, as the state-of-the-art German-made Borsig locomotive thundered through the Hejaz desert. “The dull thudding of distant artillery fire told us that we were approaching our destination,” he continued. Ever since the line was built, Bedouin gangs had been raiding the line, plundering pilgrims and extracting protection money. Each station was guarded by garrisons of troops.

Ali bin Muhammed—a model pilgrim who was in fact the English spy AJB Wavell—arrived in Medina in 1912, at the end of a long covert journey through Beirut, Damascus, and Jeddah. The reconnaissance established what his masters needed to know.

“The Bedou remain, what they always have been, independent tribes, each community having its own country, rulers, laws, and customs,” Wavell observed in his memoirs. “For many years past the Turks have found it less trouble to pay a certain sum of money to the sheikhs of the Bedou tribes through whose country the pilgrim caravans have to pass, in return for immunity from attack.”

Ottoman power was just an illusion—an illusion a few gold pieces could easily dispel.

The great train race

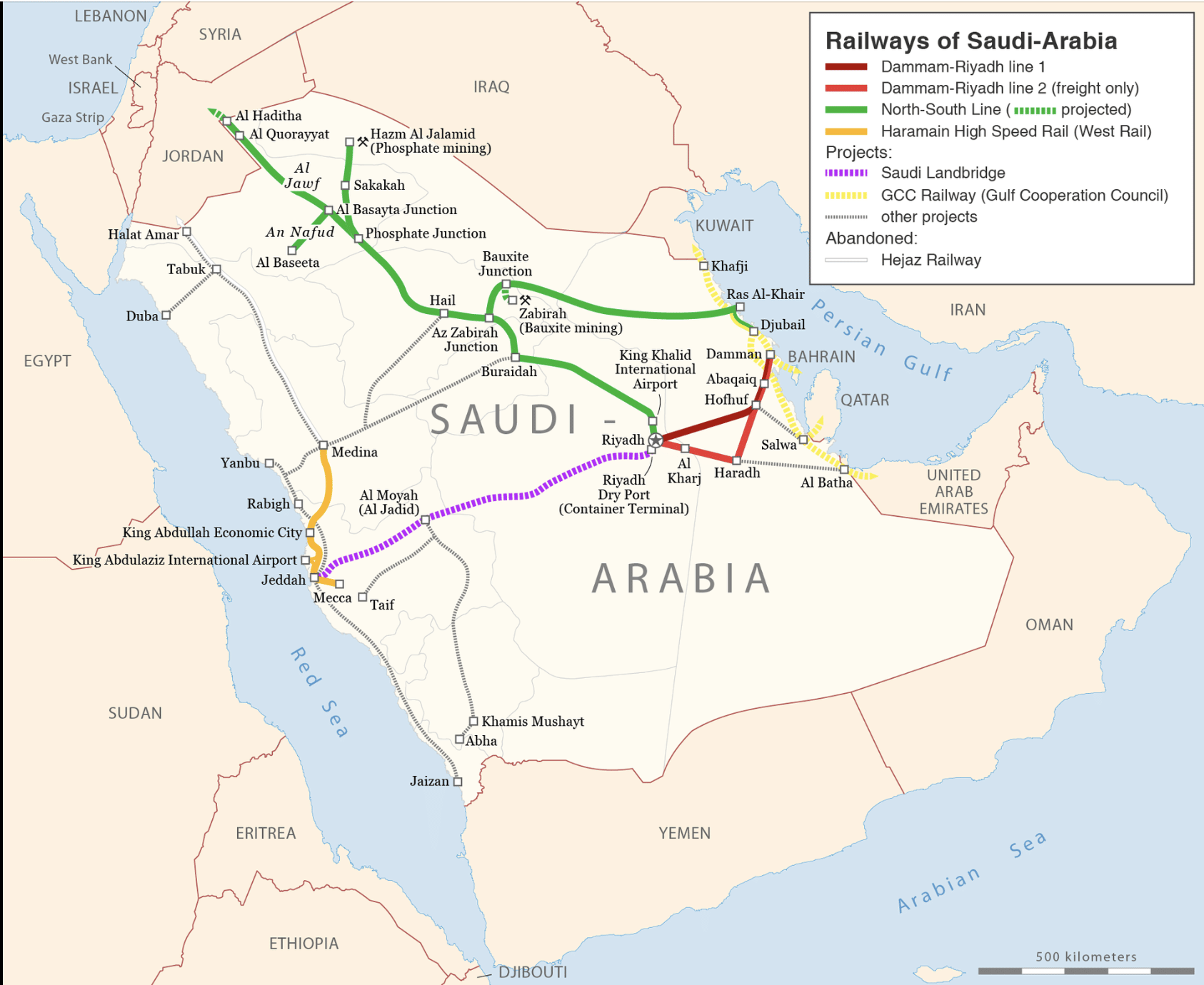

This week—just over a hundred years after the last trains ran on the Hejaz Railway—on the sidelines of the G20 summit, a coalition led by the United States, Saudi Arabia and India announced its intention to develop new networks of train lines and ports across the region. Saudi already has a sophisticated rail network, which it plans to triple. Funding is being put in place for a coastline line running through Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates.

And In 2017, then Israeli transportation and intelligence minister Yisrael Katz had announced his country’s intention to link the now Adani-owned port of Haifa through Jordan, to the new Saudi network.

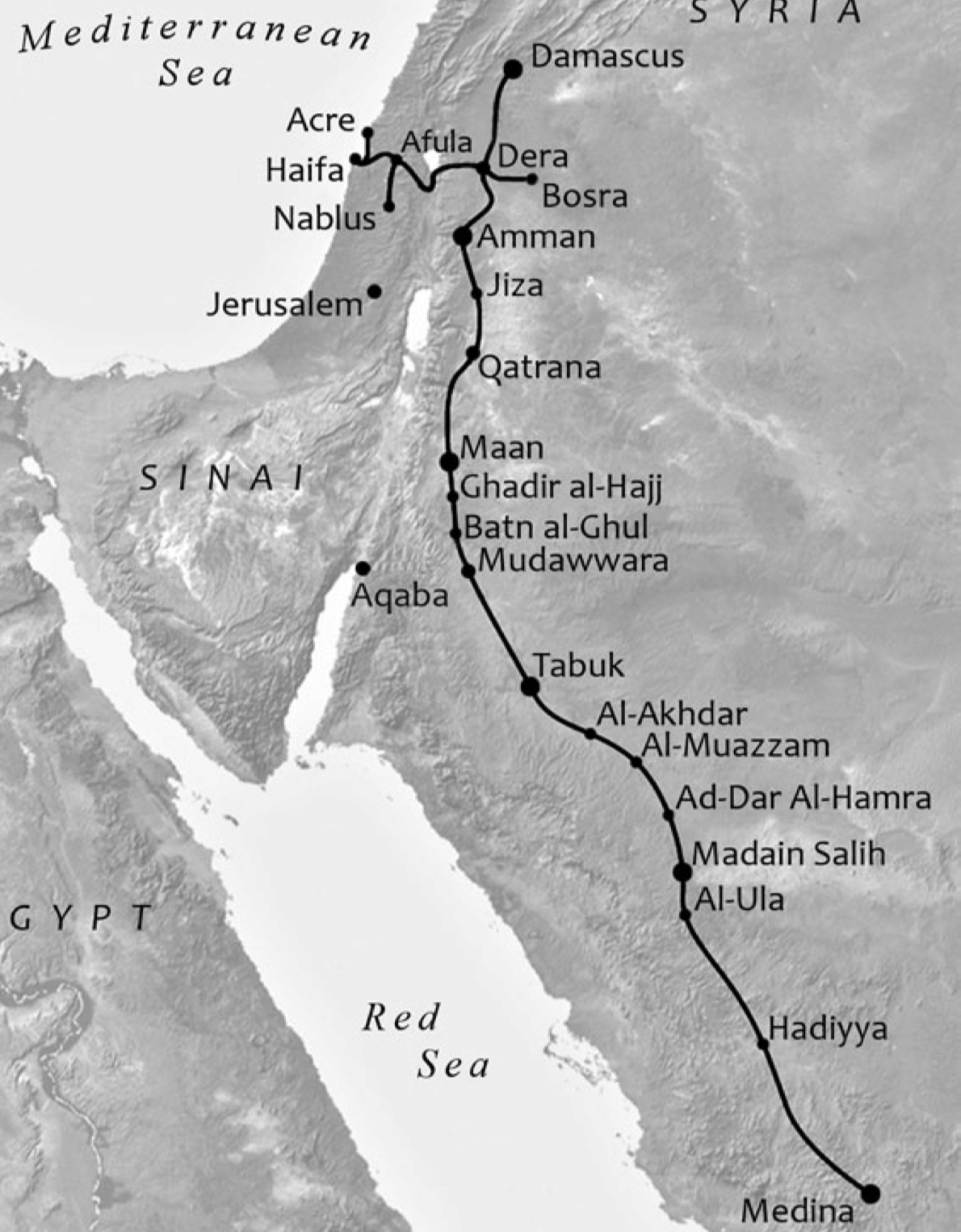

Though the United States-led Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment hasn’t made maps available so far, it’s clear the most likely route for the new network would be a line cutting north from Jeddah, and forking west towards Haifa—exactly the route of the old Hejaz railway. Future projects, it stands to reason, could head further north into Damascus, and Turkey.

Even though progress will depend on the not-quite-there Israel-Saudi Arabia agreement being hammered out, some of the fundamentals of the ideas seem evident. The bulk of the funding will come from Saudi Arabia and the West, with European technology and Indian companies providing construction capabilities and human resources. Government media in China have already been decrying the project as a “copycat” of its own Belt-and-Road rail lines.

Economic experts remain divided on the viability of the project. China’s much-hyped train lines linking it to Europe through Central Asia remain unprofitable, Shin Watanabe recently reported, because while sending freight by sea might be slower, it is much cheaper. Few commodities justify the higher costs of rail where an option is available. The train line, expert Daniel Egel has noted, would provide a security hedge if sea lanes in the Persian Gulf or Gulf of Aden are threatened—but a costly one.

The first Great Train Race, too, was about geopolitics—not just the grubby business of making money. And that, in some senses, proved its undoing.

Also Read: What Western press missed about India as Modi’s foreign policy comes of age with G20 summit

Cloud of steam, coal and gunpowder

Like other contemporary empires, the Ottomans understood the transformative power of railways. The enormous agricultural hinterland of Aydin, if linked to the port at Izmir by something more reliable than camels, would find new markets. The empire’s interests were not only economic. The train line would enable rapid troop movement to contain conflicts among Greek, Jewish and Armenian communities.

In 1857, a British corporation was granted the right to build the railway, with a guaranteed six per cent return on its capital. A race to build rail networks through the desert had begun.

Led by a consortium of Deutsche Bank, Deutsche Vereinsbank and Württembergische Vereinsbank, German investors bought rail lines leading from Istanbul to Bulgaria, and acquired the rights to build new routes towards oil-rich Kirkuk and Baghdad. The French, meanwhile, built a line from Jaffa to Jerusalem. The British, for their part, developed the route from Haifa port to Damascus.

Finally, in 1901, the last Ottoman emperor to wield absolute power, Sultan Abdul Hamid II announced the construction of a line from Damascus to Mecca, cutting through the Hejaz desert, which would be “a purely Muslim project, built by Muslim engineers using only local materials.” The Sultan had lost extensive territories with Christian populations, and now wanted to consolidate his empire’s Islamic character.

To the irritation of the British, historian Murat Özyüksel has recorded in a path-breaking work, funds began to be raised among Muslim communities in India. Muhammad Inshaullah, editor of the al-Wakil in Amritsar and al-Watan of Lahore campaigned for donations. The Imam of the Manarat Mosque in Mumbai, Abd al-Haqq al-Azhari, Princes in Hyderabad and Allahabad offered enormous sums.

Inside years of the work beginning on the line, though, Imperial Britain would be systematically blowing it all up.

Also Read: G20 shows summitry remains an ‘addictive drug’ for world leaders. But does it get work done?

Lawrence of Arabia’s war

Thomas Edward Lawrence, born in 1888, the second of five sons in a comfortable Victorian family. “The father,” historian Irving Howe has written, “a reserved gentleman who is said never to have written a check or read a book, devoted himself to domestic duties and a number of mild sports.” Lawrence learned, in 1907, that he was in fact the illegitimate child of the Anglo-Irish baronet Sir Thomas Chapman. The discovery, some speculate, led him to leave Oxford after his degree, and embed himself in what he saw as a purer Bedouin milieu.

Fighting against Ottoman forces, Lawrence pioneered the use of highly mobile irregular forces, backed by Gurkha troops from the British Indian Army and some airpower. Lawrence understood that targeting the rail line would degrade Ottoman logistics, and make it difficult for them to build up significant forces to counter his Bedouin irregulars. The charismatic leader himself claims to have personally blown up 78 bridges.

“Lawrence saw the revolt in its political wholeness and moral dynamism: not merely as it was, fouled by intrigue, cupidity and narrowness of spirit, but as it might become, an ideal possibility,” Howe observes. Though Lawrence insisted on imagining the campaign as moved by the spirit of Arab independence, massive bribery of tribes by the British is now known to have had a significant role.

The military historian Rob Johnson has noted that Lawrence’s campaign had its limits. Following its spectacular successes in 1916-1917, it slowed to a grinding stalemate as conventional forces were moved to the Western front.

Lawrence himself was captured and tortured. In his memoirs, he recalls the experience with his captor thus: “I remembered smiling idly at him, for a delicious warmth, probably sexual, was swelling through me: and then that he flung up his arm and hacked with the full length of his whip into my groin.”

For the rest of his life, historian Thomas J O’Donnell writes, Lawrence would have problems forming adult relationships with women and suffered from a fixation with flagellation. Today, this might be attributed to post-traumatic stress.

The story is an awful reminder of the human costs paid by the soldiers of imperial wars—even those who, like Lawrence, emerged as cinematic heroes. The countries the wars were fought in fared little better. The Ottoman provinces outside the Arabian Peninsula were partitioned into British and French zones of influence. Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman al-Saud set up a notionally independent Saudi Arabia, but one that was heavily dependent on Western patronage for its survival.

For its part, the last trains on the Hejaz line ran in 1920. Today, some engines still exist as museum-piece displays in Amman and Damascus, but the route is mainly useful to archaeologists investigating Lawrence’s campaign.

Will the second Great Train Race lock the Middle East into a new age of prosperity, or again lead it to become mired in catastrophic Great Power contestation? The future will soon begin to be forged with steel and fire.

The author is National Security Editor, ThePrint. He tweets @praveenswami. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)