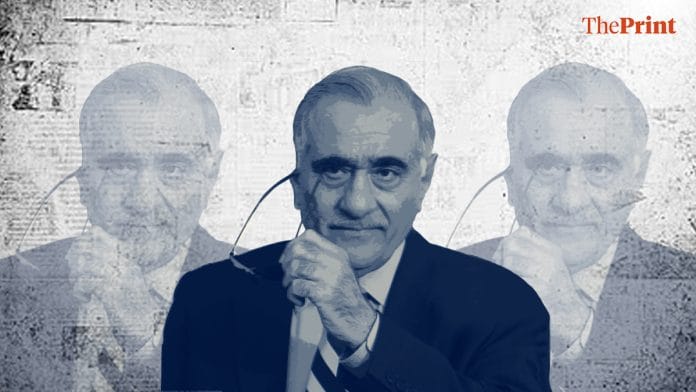

Mahmud Durrani, a long retired Pakistani Major General, was taken away at 84 last week by the heart condition he had dealt with for more than four decades. It was detected while he was in service and probably prevented the celebrated cavalryman from rising much higher.

But, he used that setback to transform himself into a different figure altogether. A man of peace, the mostly India-hating Urdu press in Pakistan often derided him as General Shanti. The Indian term for peace was preferred to the Urdu, aman, only to pile on the ridicule.

Despite his decade in peacemaking, in 2008, the new (post-Musharraf) Pakistan People’s Party government appointed him National Security Adviser. Benazir Bhutto had been assassinated in the run-up to that election and her husband Asif Ali Zardari was President. We need to also note that in his post-Op Parakram conciliatory phase Musharraf had started to lean on Durrani. He trusted him enough to appoint him Ambassador to Washington where he was trying to clean up Pakistan’s act.

Durrani as NSA was a big leap for Pakistan and no surprise that he didn’t even last a year in that job. He chafed after 26/11, seeing it as a deliberate Army/ISI betrayal and sabotage of the prospects of peace. Under pressure from global outrage Zardari offered to send him, his NSA, to India to coordinate investigations and rebuild confidence. The powers that be were furious and overruled this.

Durrani, however, wasn’t one to put up with this. In the first week of January 2009, barely five weeks after 26/11, he emphatically told the media that Mohammed Ajmal Kasab was indeed a Pakistani and it made no sense to hide that truth. He was made to resign immediately. Later, on visits to India in 2009 to deliver the R.K. Mishra Memorial Lecture at Observer Research Foundation (ORF) and then in 2017 to speak at the Institute of Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA), he not only repeated the same truth but elaborated on it. He said he had no doubt whatsoever that the ISI had staged 26/11.

You have to have that special courage to say this while living in Pakistan. Especially if you are a respected veteran, a decorated combatant in the 1965 war and a former NSA. That’s the courage Durrani had. He was totally a Pakistani patriot and would volunteer to go to the front if war broke out again. He just believed his country and people’s interest was best served by avoiding that war, ideally, permanently. That’s why he fought for peace.

He’d also laugh away the ridicule and wear with pride that epithet of General Shanti as a badge of honour.

Also Read: How Pakistan thinks: Army for hire, ideology of convenience

Here’s how he pursued his peacemaking. For two decades he was key to high-powered India-Pakistan Track-II groups, then encouraged by both governments, generally in the 1995-2005 decade. I participated in three of about a dozen held under what was called the Balusa Group of a dozen people, about eight regulars and the rest floaters.

These included, from the Indian side, former IAF chief Air Chief Marshal S.K. Kaul, his brother and former cabinet secretary P.K. Kaul, and former R&AW chief and J&K governor G.C. ‘Gary’ Saxena; from the Pakistani side were often top former civil servants, at least once former Army chief, Jehangir Karamat, and relatively younger politicians, Shahid Khaqan Abbasi and Shah Mehmood Qureshi, the former rose to prime ministership and the latter became foreign minister. whatever those jobs might count for in their country.

As you can guess from the few names I have mentioned, most of the participants had been combatants from rival sides, militarily, diplomatically, covertly, or in strategic debates.

For the odd editor, it was an enormous learning experience as the top practitioners on the two sides talked. Sometimes conversations carried on into hour-long walks. I kept memories, and sort of uncharacteristically, even some notes from one with Durrani and a couple of others along Lake Bellagio in Italy. As we go along I will share some of these with you.

See it this way, if some plumbing and wiring in his heart hadn’t caught the attention of his military doctors and he rose to be a three- or even a four-star, we would perhaps not be writing obituaries for him in India. Because, even if he became chief, he’d be among the few who had no political delusions. He also believed military interference was at the root of many of Pakistan’s problems.

Because of his health challenges he was taken away from combat unit commands and seconded out to head Pakistan Ordnance Factories Board. Given his age and pedigree, he had seen two Pakistani dictators, Zia and Musharraf, up close. He also served both, Zia as military secretary, and Musharraf as his envoy to Washington.

Also Read: India doesn’t give walkovers to Pakistan in war. Here’s why it shouldn’t do it in cricket either

Two conversations from that long, lakeside walk stand out. The first, when I asked him if Zia was indeed as much of an Islamist as we believed. He didn’t start out as one, Durrani said. He was just another garden variety (my words) normal, devout Muslim. But, as one audacious move after another worked for him—the coup, jailing and hanging of Bhutto—people around him would tell him he was divinely chosen and empowered to restore the glory of Islam in Pakistan. This was greatly compounded after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Pakistan finding itself centre-stage in that ‘jehad’. ‘See, what have we been telling you,” the same hangers-on would tell him now, “everything, from Bhutto making you army chief over the heads of others, your coup, Bhutto’s hanging, were all planned by the almighty. All to position you for this jehad. Allah had needed and wanted you here.”

Durrani said by this time Zia had started to believe all of this, that he was the chosen one. He said he’d been to Mecca with Zia early on and he prayed like the usual believing Muslim. Now he would sit by the grave sometimes for more than an hour, even crying in emotion. His success and hangers-on had made him an Islamist. They took away his life too.

Durrani had been Musharraf’s instructor in at least one of the military academies. After Musharraf seized power and upped terror attacks in India, Durrani said he went to see and upbraid him. Something must have stayed with Musharraf who reached out to him for the Washington job. Remember, this was also the period that Musharraf worked closely with Vajpayee and later Manmohan Singh for a settlement.

In 1965, Durrani fought as a cavalry major in the Sialkot sector against the advancing Indian strike Corps (2nd) and 1st Armoured Division. He generally had a young officer’s scepticism over the capability of rival cavalry commanders and said both sides were insipid, routine and totally unspectacular in their tactics. In all of that war, he said, he saw one truly brilliant move. This was the Poona Horse Regiment led by Colonel A.B. Tarapore. That attack came from a completely unexpected and really clever direction and ‘threw us back’. It was just the vagaries of the battlefield that a random artillery shell hit Tarapore’s tank. Tarapore, as we know, was awarded a posthumous Param Vir Chakra (PVC). Incidentally, Second Lieutenant Arun Khetarpal of the same regiment, whose story the new Bollywood release Ikkees features, won a posthumous PVC for his display of valour in the same sector in 1971.

We continue Durrani’s story from 1965 though. Later as dust settled on that battle, he said, just a little bit hesitatingly “we went rummaging through tank wreckages as is routine among us soldiers, I picked up and kept Tarapore’s cap and swagger stick”.

I suggested to him that returning these to his family or regiment might indeed be a good peaceable move. I am not sure he ever did it. But if his family has these, and happens to read this, it will be an excellent idea to hand these over now as a gesture for all the peace he fought for. It will be the best tribute to the legacy of General Shanti.

Also Read: For Indian Mercedes, Asim Munir’s dumper truck in mirror is closer than it appears

And so endures the myth of the Pakistani liberal…