India approaches the Union Budget season with a rare degree of global confidence. The International Monetary Fund has consistently identified the country as the fastest growing major economy and a significant contributor to global economic growth, particularly at a time when most of the other regions are experiencing a slowdown. This assessment is indicative of robust domestic demand, public investment, and macroeconomic stability. However, maintaining this momentum necessitates an examination beyond mere headline growth figures. It requires critical analysis of India’s production, import patterns, and underlying reasons.

Within this analysis lies a subtle contradiction: India remains reliant on imports in sectors where it should not be.

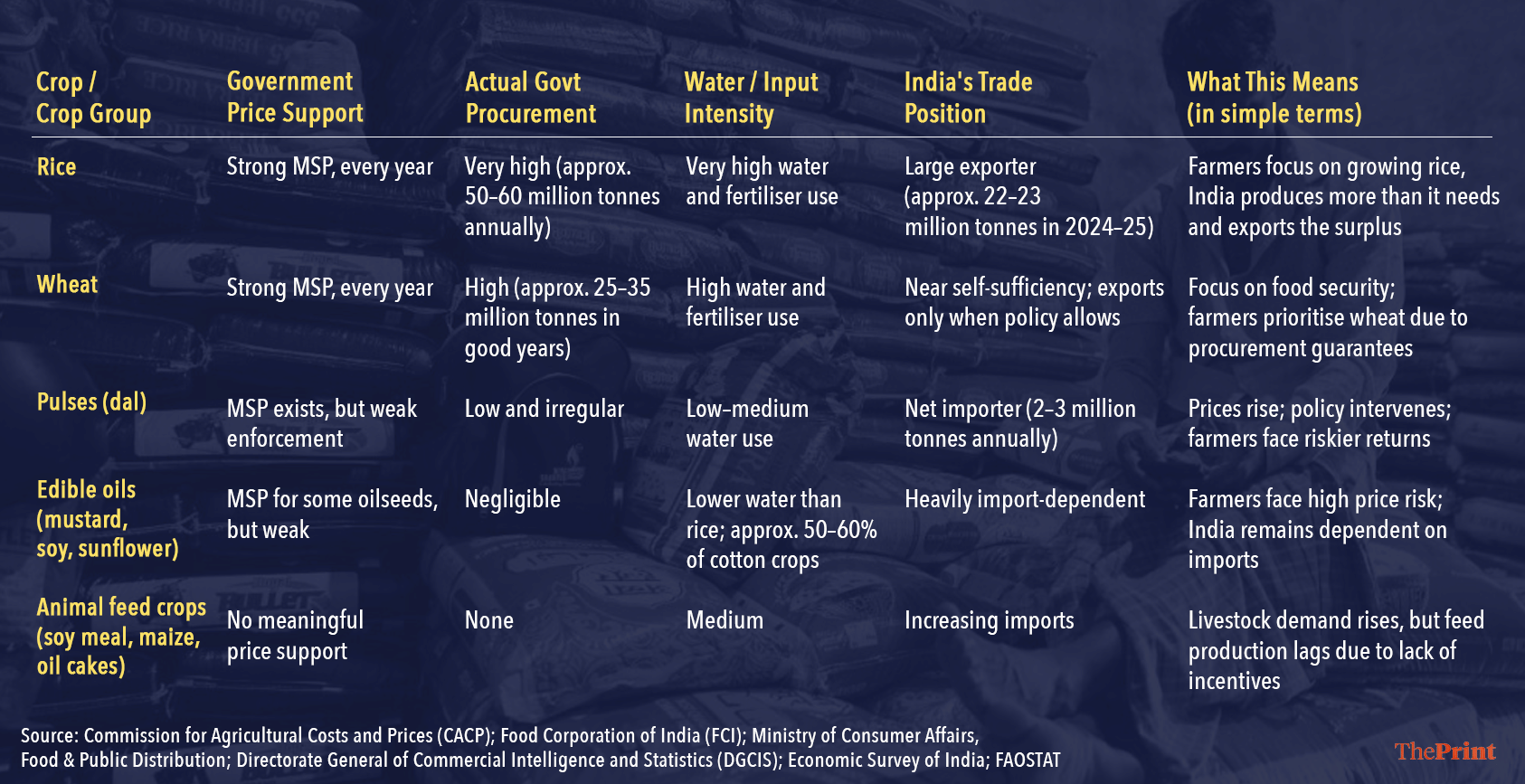

This is most evident in the food and agriculture sectors. Despite being one of the largest global producers of crops, India imports approximately 60 per cent of its edible oil consumption, regularly imports 2-3 million tonnes of pulses, and is increasingly reliant on imports for animal feed. At the same time, rice production consistently surpasses domestic requirements, necessitating either exports or costly storage solutions. This simultaneous occurrence of surplus and shortage is not quite imposed by nature, but rather shaped by policy.

When price control distorts production

Governments globally express concern regarding food inflation and India is no exception. When the prices of essential commodities increase, political pressure escalates rapidly. The immediate reaction is to impose export restrictions, reduce import duties, and release buffer stocks. These interventions often succeed in mitigating price increases in the short term.

However, what is less frequently examined is the impact of these measures on long-term production patterns. Farmers make decisions several months prior to harvest, investing in seeds, fertilisers, and labour, based on anticipated prices and policy conditions at the time of market entry. When prices rise one year but markets are abruptly closed the following year, farmers learn a straightforward lesson: the potential for profit is temporary, while the risk of loss is permanent. Over time, they tend to favour crops for which the state mitigates price risk through assured procurement, and avoid crops where policy responses are unpredictable.

This phenomenon explains why India produces an excess of rice and insufficient oilseeds. It is not due to farmer conservatism or a lack of capability; rather, it is a rational response to the incentives presented.

Trade serves to then fill these gaps engendered by domestic policy. Imports mitigate the shortfall in production that is discouraged by policy itself. What may be perceived as reliance on global markets is, in fact, dependence cultivated domestically. The fiscal implications are significant and persistent. Public funds are allocated to the procurement, transportation, and storage of surplus grain, while additional resources are deployed to manage imports through tariff adjustments and ad hoc interventions. These expenditures recur solely because the underlying incentive structure remains unaltered.

Also read: Budget 2026 must signal rail reform. End cross-subsidies, privatise operations & services

Concentration and complexity: what the numbers reveal

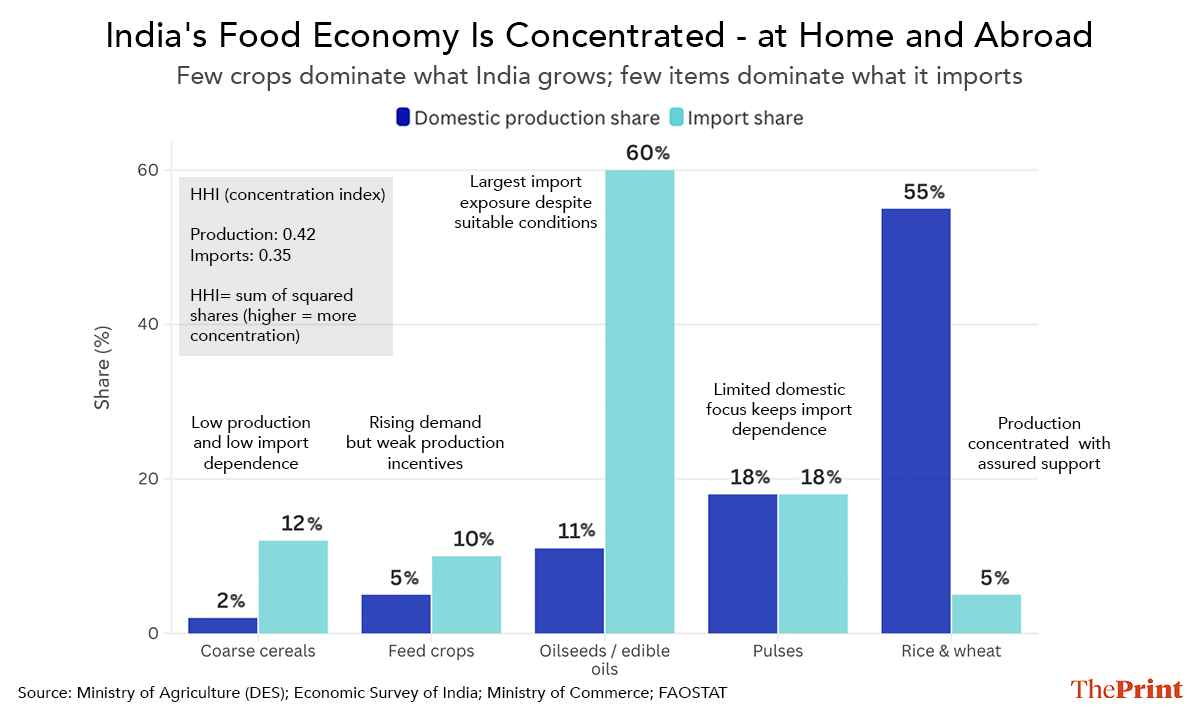

Economists often use the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) as a metric to assess market concentration. In simple terms, it evaluates whether production or sourcing is diversified or dominated by a limited number of items or suppliers. A high HHI indicates vulnerability, whereas a lower HHI suggests resilience.

From this perspective, India encounters a dual concentration issue. Domestically, agricultural production is concentrated in a limited range of crops, with rice and wheat predominating in terms of land use and public expenditure. Internationally, imports of edible oils and pulses are sourced from a restricted number of countries. This combination renders the system fragile, as any climatic shock, global price surge, or geopolitical disruption can have a disproportionately large impact.

There exists a more profound concept that explains the persistence of this concentration: the Product Complexity Index (PCI). As I discussed in a column of mine from September 2025, the PCI does not measure the monetary value of a country’s production but rather the knowledge embedded within it. Products that are easily manufactured by numerous countries are ranked low, whereas those necessitating advanced capabilities and coordination are ranked high. Nations that move up the PCI ladder tend to experience accelerated growth, diversify with greater ease, and exhibit increased resilience to economic shocks. Even though this concept is primarily applied to manufacturing, it matters just as much in agriculture.

Rice and wheat, while fundamental, are characterised as low-complexity products. Their production requires minimal coordination beyond the agricultural stage and results in limited spillover effects. In contrast, oilseeds, pulses, protein crops, and processed foods exhibit greater complexity. These products require advanced seed systems, efficient storage, processing capabilities, logistics, and market integration. They contribute to higher income per hectare and establish connections with related industries. In short, their complexity is the very attribute that makes them valuable for sustainable long-term growth.

India faces a challenge wherein policy certainty is strongest for the simplest products and least assured for the more complex ones. When complexity is met with uncertainty, production tends to concentrate in areas where risk is mitigated, capability development is hindered, and imports increase.

This pattern is not confined to the agricultural sector alone. The broader Indian economy similarly exhibits a propensity to expand in scale more rapidly than in depth. The consistent lesson is that complexity does not arise spontaneously; it requires stable incentives and patience.

Also read: The Budget faces a precarious illusion. Low inflation masks a deeper fragility

What can the Budget change?

Addressing these issues does not require dismantling of food security systems or the abandonment of consumer protection measures. Instead, it requires establishing credibility.

Farmers require assurance that trade policies will not suddenly impose export restrictions or flood markets with imports when prices increase, rather than a need for consistently high prices. Transparent, rule-based trade responses are more effective in enhancing oilseed and pulse production than repeated ad hoc interventions. Buffer stocks can stabilise markets, but they should serve as complements to production incentives. Reducing domestic concentration is the most reliable method to decrease foreign dependence.

The Union Budget can signal this transition by allocating fewer resources to surplus management and more toward enabling diversification, while acknowledging that short-term price controls can undermine long-term capacity. The economic principle is evident: unstable incentives foster dependence. Import dependence is not an inevitability; it is a matter of policy and policy can be rewritten.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)