As the Union Budget 2026 approaches, public capital expenditure is poised to once again take centre stage.

Over the past decade, and particularly since the onset of the pandemic, the Indian government has increasingly acted as the investor of first resort—intervening when private balance sheets were under strain, credit demand was weak, and uncertainty prevailed. Sectors such as roads, railways, ports, power, and logistics have benefitted from sustained public investment, establishing capital expenditure as the government’s preferred mechanism for stimulating growth. This strategy deserves credit for stabilising the economy during a period of significant disruption and averting a more severe and prolonged investment downturn.

However, it is now time to ask a harder question: Does public capital expenditure continue to yield the same economic benefits it once did?

The data indicate a more complex scenario. While public investment continues to encourage private investment, its impact is less pronounced than before. Moreover, the transmission from public capital expenditure to industrial demand and capacity utilisation remains weak. This does not imply that public capital expenditure has failed, but rather that its role within the growth strategy must now evolve.

The shrinking multiplier

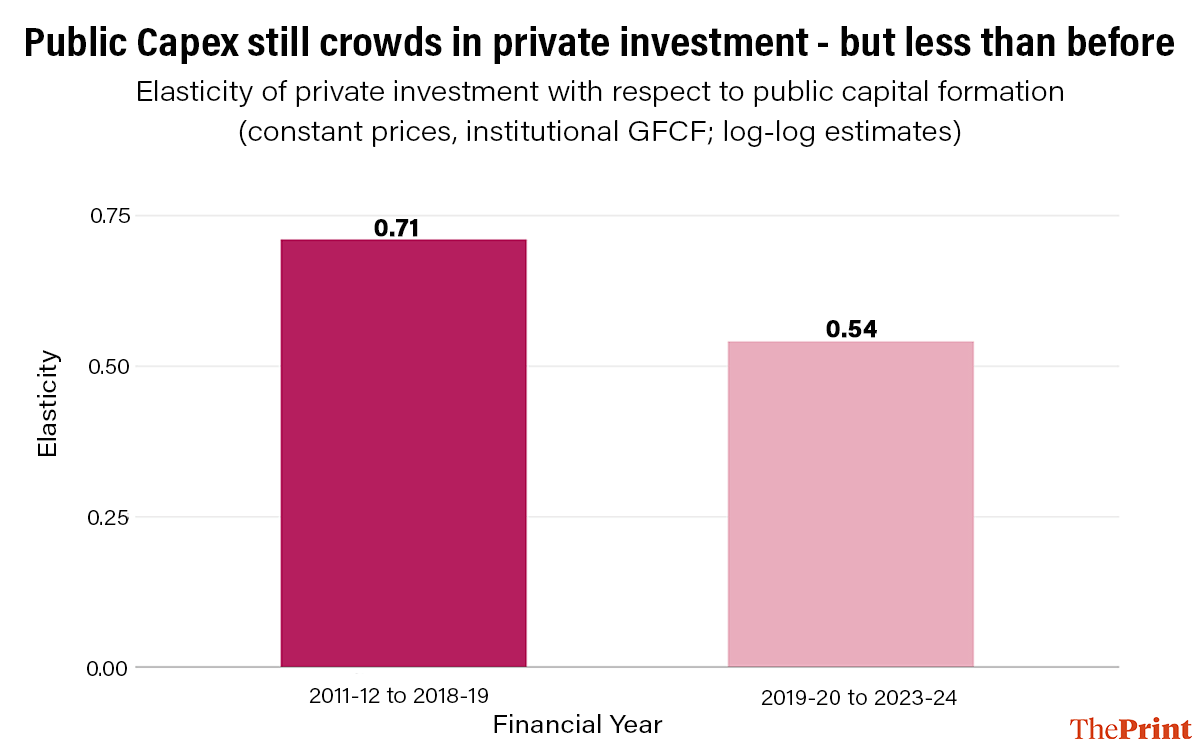

This chart estimates the elasticity of private investment in relation to public capital formation, using national accounts data at constant prices. In the pre-pandemic period (2011-2012 to 2018-2019), the relationship is both strong and statistically robust: a 1 per cent increase in government capital expenditure is associated with an approximate 0.7 per cent increase in private investment. This pattern shows the concept of “crowding in,” where public investment eases constraints, improves expected returns, and incentivises private firms to invest alongside the state.

After 2019, this elasticity declines to approximately 0.54. Although the coefficient remains positive and statistically significant, its magnitude is noticeably reduced. This shift suggests that while public capital expenditure continues to support private investment, each additional unit of government spending now generates a weaker private-sector response than before. Public investment is increasingly compensating for private-sector caution rather than catalysing a self-sustaining private capital expenditure cycle.

This observation does not constitute a critique of the government’s capital expenditure initiatives. Instead, it reflects diminishing marginal returns from the prolonged application of the same policy instrument within a changing economic context.

Why stronger public capex hasn’t tightened capacity

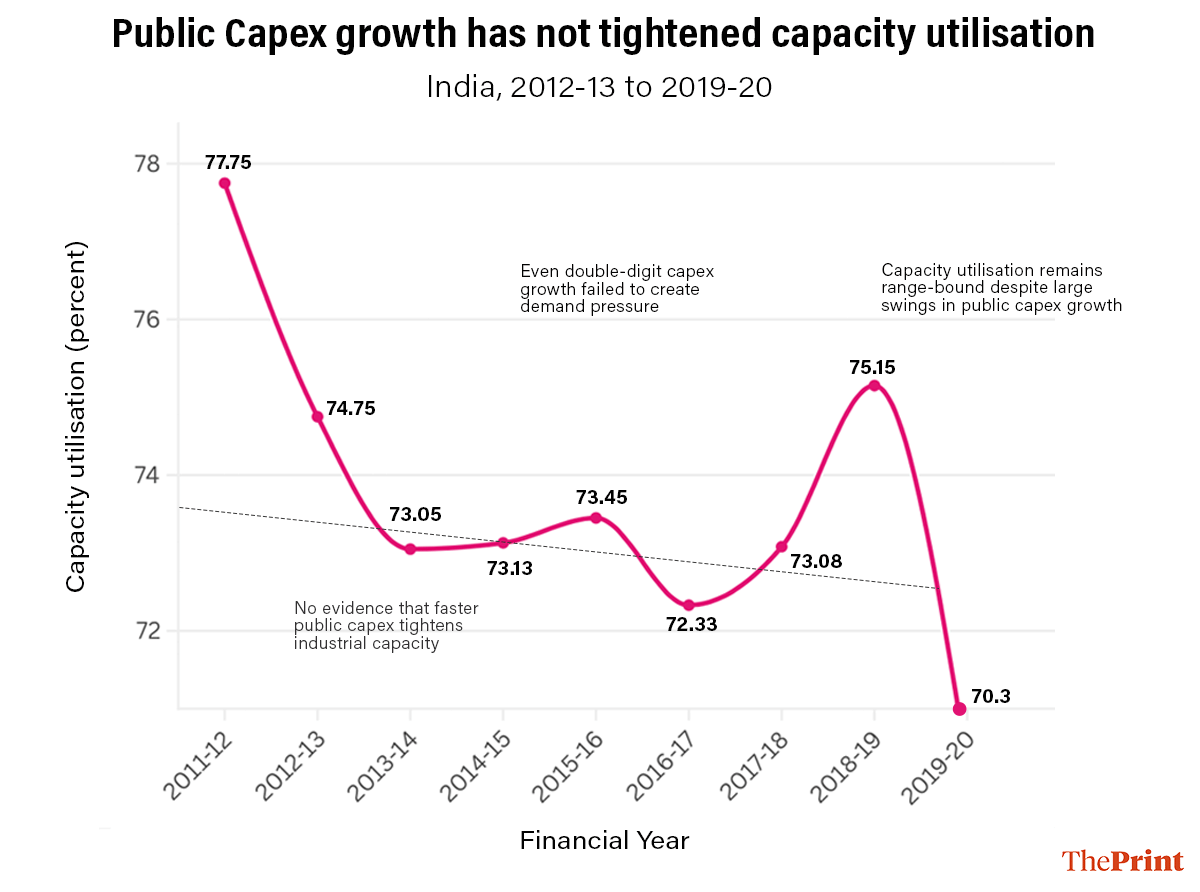

If public investment were effectively stimulating demand, it would be reflected in higher industrial capacity utilisation. Rising utilisation would indicate that firms are operating closer to full capacity and would, in turn, necessitate fresh investment for expansion. However, such an indication remains absent.

Chart 2 illustrates the annual growth in public capital expenditure (capex) against manufacturing capacity utilisation, using data from the Reserve Bank of India’s Order Books, Inventories and Capacity Utilisation Survey (OBICUS). The pattern is noteworthy: capacity utilisation remains consistently within a narrow range, predominantly between 72 and 76 per cent, despite significant fluctuations in public capex growth. Even during periods when public capex growth reached double digits, capacity utilisation does not show sustained tightening. Indeed, the correlation between accelerated public investment growth and capacity utilisation appears to be weakly negative.

The conclusion: while public capex has expanded supply, it has not generated sufficient final demand to propel manufacturing into a new, self-sustaining investment cycle.

Infrastructure without demand is not enough

The observed disconnect helps explain the uneven recovery of private investment. Large corporations within capital-intensive industries, possessing strong balance sheets, have engaged in selective investment. However, within a significant portion of the manufacturing sector, firms exhibit caution, prioritising deleveraging and efficiency over expansion. Three structural factors contribute to this phenomenon.

First, the composition of public capital expenditure is significant. A substantial portion of the recent increase has been allocated to large infrastructure projects—such as highways, rail corridors, logistics parks—which have extended gestation periods. While these investments enhance long-term productivity, they do not immediately generate demand for manufactured goods.

Second, consumption growth has been inconsistent. Rural demand has only recently begun to recover, urban consumption is predominantly oriented toward services, and wage growth remains inconsistent. In the absence of stronger and more predictable final demand, firms have limited incentive to expand capacity, irrespective of infrastructure availability.

Third, uncertainty continues to influence private investment decisions. Global demand is volatile, trade conditions are evolving, and regulatory and tax unpredictability continue to impact risk-adjusted returns. Although public capital expenditure can reduce costs, it cannot eliminate uncertainty.

Also read: Why India needs more mining to power its manufacturing future

What Budget 2026 needs to rethink

The lesson for fiscal policy is to maintain public investment rather than withdraw from it. India requires infrastructure, and reducing capital expenditure would be counterproductive. However, the period during which simply increasing public capital expenditure could independently drive growth is coming to an end. The 2026 Budget must view capital expenditure as a catalyst, rather than a substitute.

Public investment should be complemented by measures that support demand. Stronger consumption, achieved through employment generation, urban demand support, and income growth, is crucial for ensuring that the capacity created is effectively utilised.

The government must mitigate policy uncertainty for private investors. Stable taxation, faster dispute resolution, predictable trade policy, and sector-specific regulatory clarity are as significant as infrastructure quality.

Public capital expenditure should increasingly aim to de-risk private investment rather than overshadow it. Instruments such as viability gap funding, public-private partnerships, and targeted credit guarantees can more effectively attract private capital than direct state spending alone.

Finally, fiscal policy must acknowledge its limitations. While public investment can construct roads and railways, it cannot manufacture confidence.

India’s public capital expenditure initiative has played a pivotal counter-cyclical role during periods when private investment was either reluctant or unable to step up. This initiative has contributed to capacity building, addressed infrastructure deficiencies, and stabilised economic growth. That phase is largely complete.

The next phase necessitates a more challenging endeavour: the revitalisation of private sector risk appetite. This will rely less on the magnitude of government expenditure and more on whether firms perceive demand as sustainable, policies as predictable, and returns as commensurate with the risks involved.

As the 2026 Budget approaches, the pertinent question is no longer whether public capital expenditure should remain elevated—it should. The critical inquiry is whether fiscal policy can now achieve what public investment alone cannot: establish the conditions necessary for private investment to assume a leading role.

Public capital expenditure has propelled the economy this far; however, it cannot sustain the momentum independently.

Bidisha Bhattacharya is an Associate Fellow, Chintan Research Foundation. She tweets @Bidishabh. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

A most interesting insight… It is fairly common knowledge that for every 100 spent on large infra projects, only about 50/60/70% actually makes it into the project & the rest is syphoned off into other accounts. Can the economist also factor in this aspect into the analysis? Does it have any bearing on the economic benefits that will accrue?