In October 2025, the Ministry of Law and Justice inaugurated the “Live Cases” dashboard under the Legal Information Management and Briefing System (LIMBS) to effectively manage and reduce government litigation. Earlier this year, the Ministry also notified the “Directive for the Efficient and Effective Management of Litigation by Government of India” to curb contractual disputes involving the State.

This heightened policy attention to reduce the volume of commercial litigation in which the government is a party, is a positive step toward improving the ease of doing business with the State. It suggests that there is an appetite within the government for the settlement of contractual disputes.

Three ideas shape the discourse on commercial litigation involving the government: that the volume is large, that the government is unusually litigious, and that it slows down the court process.

We test these claims in this article, using data from the Delhi and Bombay High Courts for eight years (2017-2024). We analyse the volume and duration of cases involving the government’s commercial activities, such as where the state is an economic actor engaging in procurement, contracts, and service delivery.

What is the size of government commercial litigation?

At the outset, we identify cases pertaining to commercial activities of the government. These are of four types: arbitration cases, such as challenging arbitral awards or seeking the appointment of an arbitrator; commercial suits that involve enforcement of government contracts, execution applications to enforce arbitral awards and court decrees, and regular non-contractual suits to which the government is a party, such as a suit for damages for wrongful injury.

Contract claims against the government may be enforced through “writ petitions” as they generally see quicker progress in courts. Our analysis does not include such cases because they cannot be easily segregated into commercial claims and claims relating to the enforcement of the litigant’s fundamental rights.

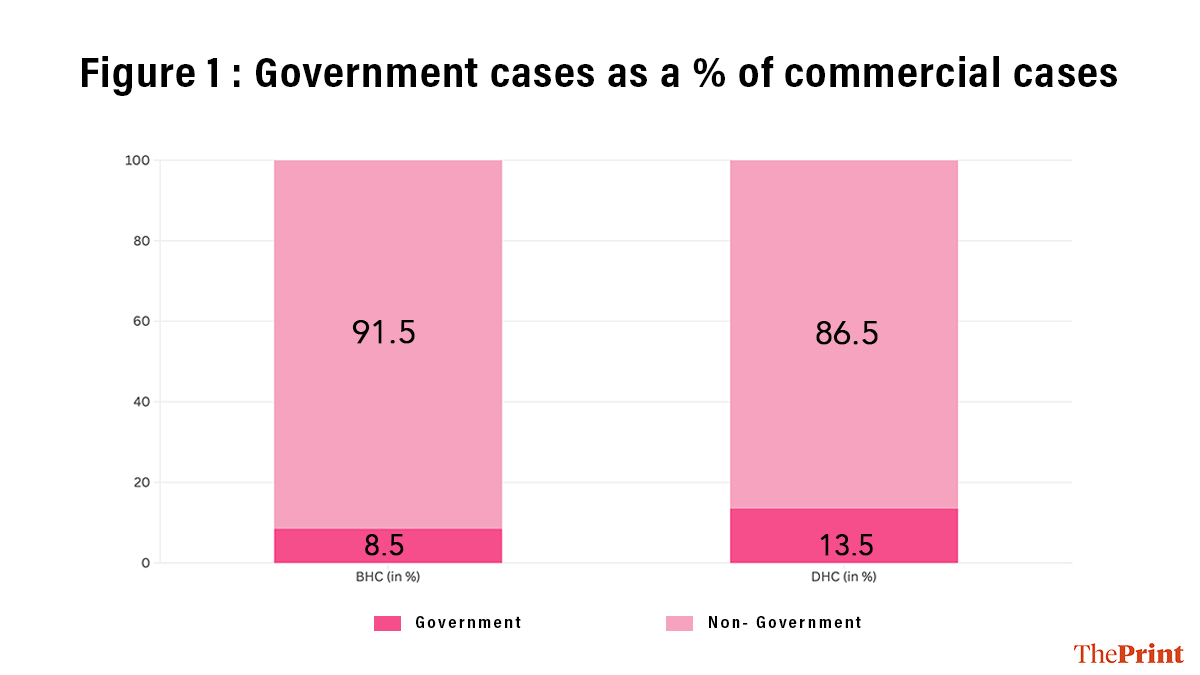

Figure 1 : Government cases as a % of commercial cases

Table 1 above shows that the government accounts for 8.5 per cent of commercial litigation in Mumbai and 13.5 per cent in Delhi. This is a small fraction of total commercial disputes, given the government’s level of expenditure for procurement activities.

This finding suggests that reforms that focus on reducing government commercial litigation—will not make a dent in a court’s caseload or pendency.

That said, from the government’s perspective, a relatively lower fraction of government commercial disputes may suggest a selection bias, where only large firms find it feasible to litigate against a counterparty with superior bargaining power and the ability to finance lengthy appeals.

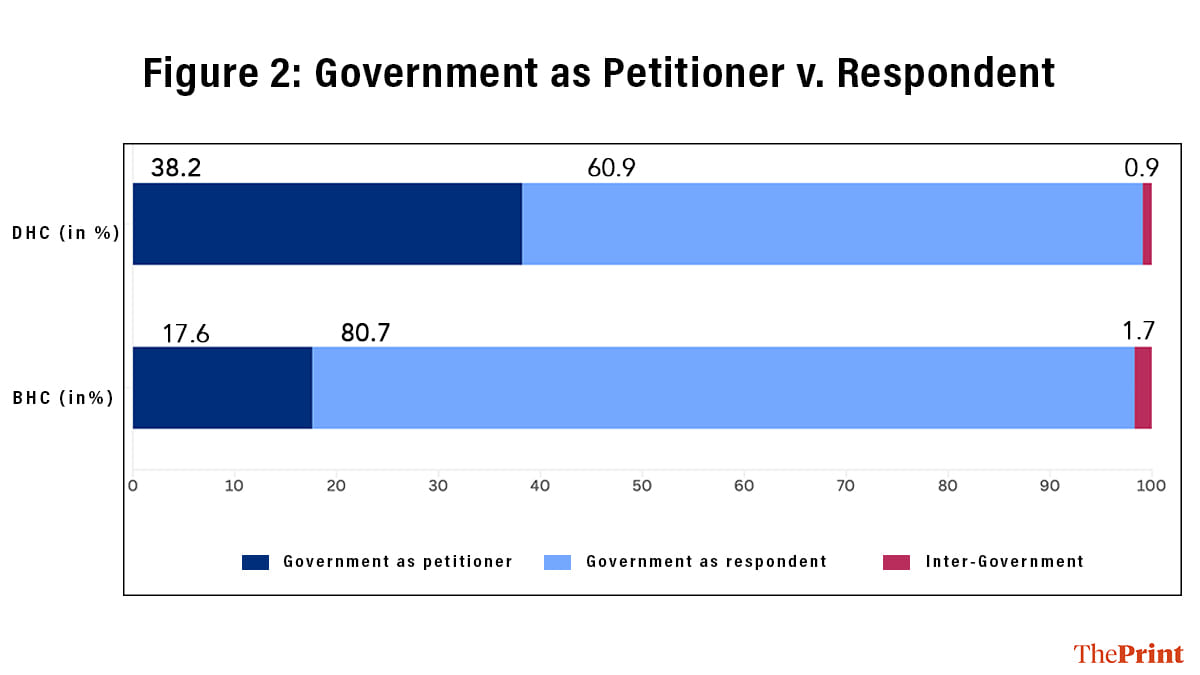

Is the government suing or defending?

Next, we identify the cases that the government initiated. In the Bombay High Court, less than 20 per cent of the government litigation is initiated by the State. In the Delhi High Court, there is a 40-60 split between the government as a petitioner versus the respondent.

Figure 2: Government as Petitioner v. Respondent

This pattern implies that the government is often accused of breaching its commercial obligations. It points to failure in managing and performing contracts rather than litigiousness. When the State mostly appears as a respondent, the underlying problems is likely non-performance of contract, delayed payments, or weak dispute-redress mechanisms and slow decision-making inside departments and agencies. These are instances that force counterparties into litigation.

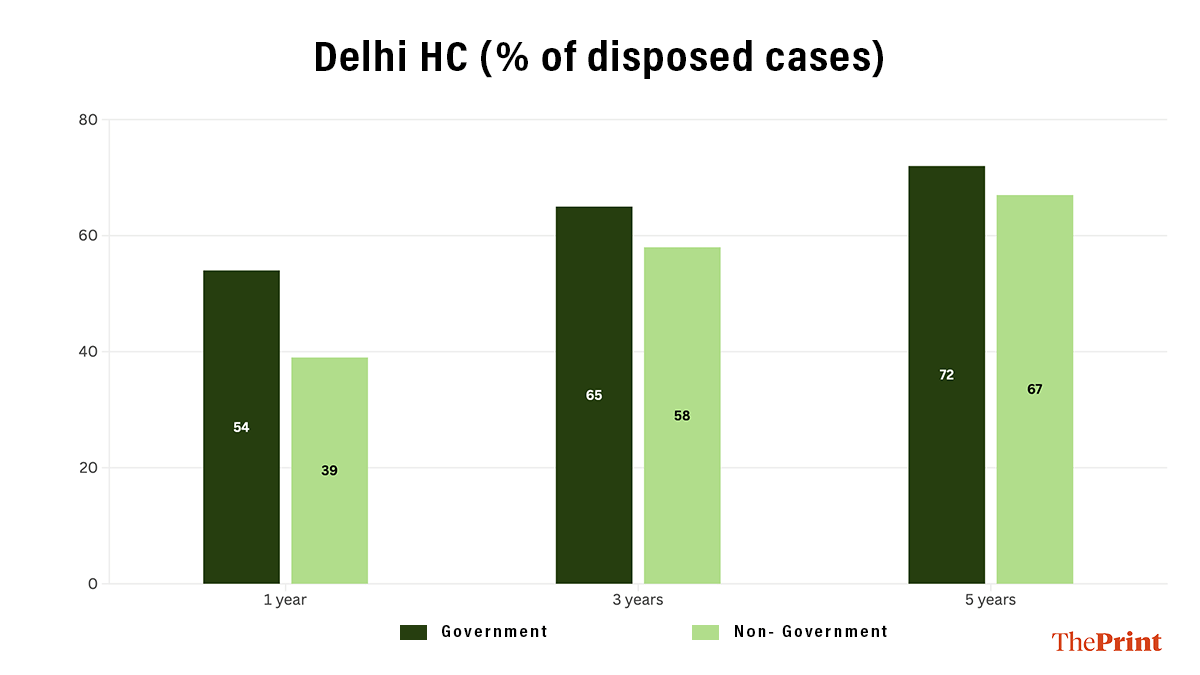

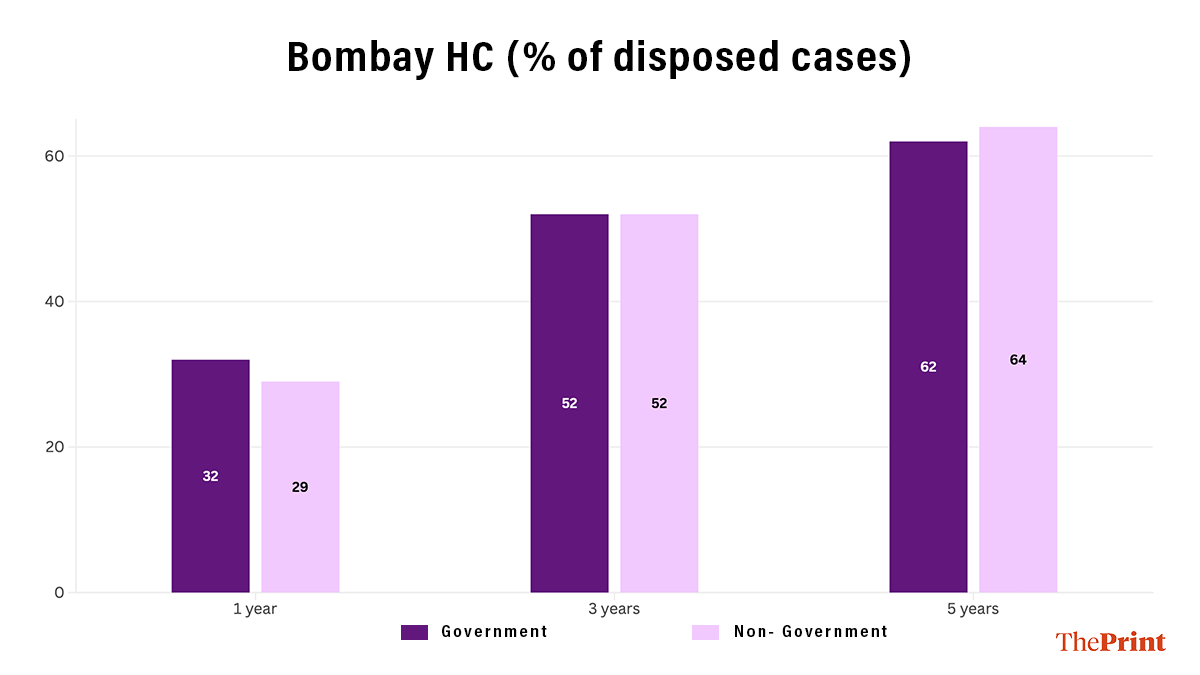

Does the government drag its feet in court?

Finally, we examine whether there is a difference in the time to resolution when the government is a party to a dispute. The data does not support the conventional claim that the government “drags its feet” once a case reaches court. Table 3 below shows that, irrespective of the court, a higher proportion of government cases get disposed of within 1 year than non-government cases.

Figure 3: Proportion of disposed cases

However, as time progresses, this difference narrows at the Delhi High Court and reverses, albeit marginally, at the Bombay High Court. That is, only a small subset of long-tail government cases get stuck in court, possibly complex disputes, and high-value matters.

Also read: India’s much-maligned intelligence agencies are our only hope against terror attacks

Implications for reform

Evidence on the scale of government’s commercial litigation and the probability of such cases reaching an outcome at these courts has implications for both the parties, vendors working with the government, as well as the government.

For firms, this holds insights into the costs of doing business with the government and the resources and strategies required to deal with such litigation.

For policy-makers, real gains can be achieved when the government focuses its reforms upstream in better contract design, stronger capacity to monitor performance and maintain documentation, and downstream in systems that guide case-flow management and timely settlement decisions.

The authors are researchers at XKDR Forum and The Professeer. Views are personal.

(Edited by Ratan Priya)

What about administrative litigation and inter state litigations??