India’s mergers and acquisitions market is getting bigger, but quieter. Deal values hit $14 billion in Q3 2025, up 50 per cent from the year before. Yet, fewer deals are closing. Companies are doing larger but fewer transactions, and smaller deals are falling away.

Mergers are important because they offer real exits to shareholders, and enable firms to grow bigger, allowing them to optimise economies of scale and create surplus for consumers. For a government that wants to focus on ease of doing business and has aspirations of a $7.3 trillion economy, months lost in tribunal queues carry a real cost to shareholders and Indian firms wanting to grow.

In her Union Budget 2025 speech, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman offered a diagnosis. Requirements and procedures for speedy approval of company mergers were to be rationalised, and the scope for fast-track mergers widened. In September, the Ministry of Corporate Affairs followed through. The Companies (Compromises, Arrangements and Amalgamations) Amendment Rules, 2025 expanded the fast-track merger framework, allowing unlisted companies with borrowings under Rs 200 crore, holding-subsidiary mergers, and fellow subsidiary restructurings to bypass the tribunal entirely, getting approval directly from the Regional Director.

It was an acknowledgement that the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT), the single window meant to speed up corporate restructuring, has become a bottleneck. At The Professeer, we analysed 3,376 merger cases filed after 2021 across all benches to understand exactly where deals go to wait. These cases account for a fifth of the caseload of the tribunal today.

NCLT timeline for mergers

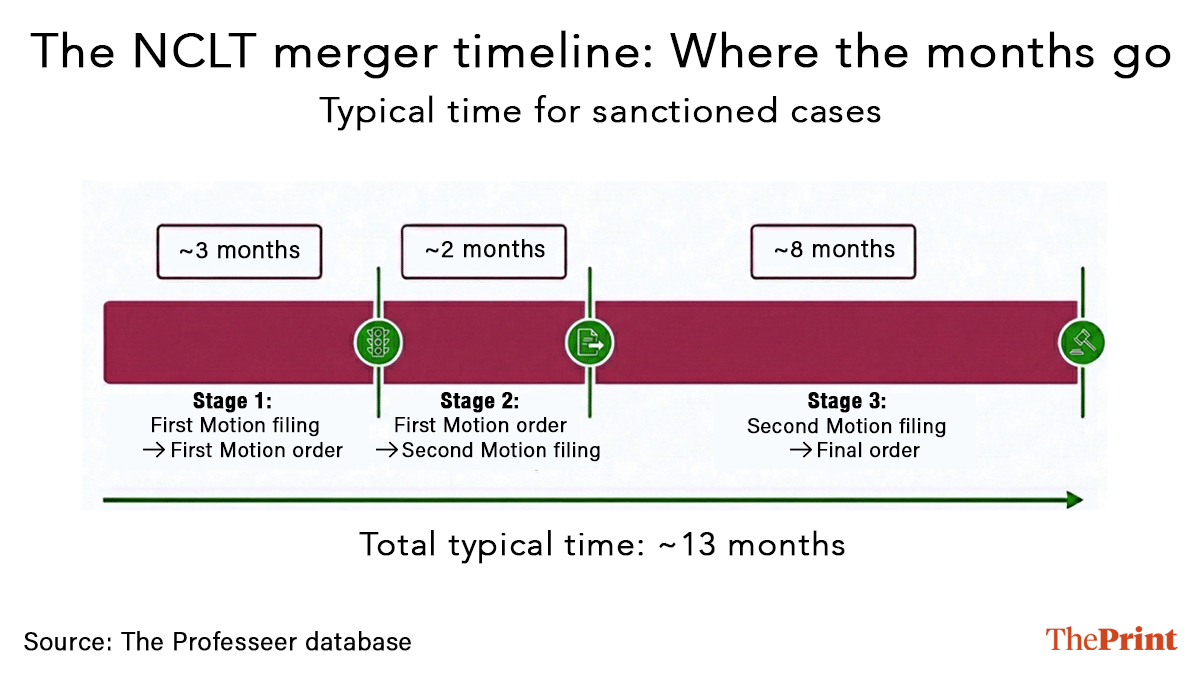

On paper, a merger through NCLT should take 90-120 days. First, the company files an application. Let’s call it the First Motion, the green light to talk to stakeholders. The tribunal decides whether shareholders and creditors need to formally vote, or if that requirement can be waived. Then comes a 30-day window for regulators – the Regional Director, Income Tax, Registrar of Companies, and others – to raise objections. Finally, the company files a Second Motion, and the NCLT approves or rejects the scheme. This approval may be conditional or unconditional.

In practice, the typical case takes over a year. Among almost 2,500 cases with recorded outcomes, the median time from first filing to final order was nearly 13 months. When we account for cases that are still stuck in the system, using a method called survival analysis, the wait time is even longer: 16 months. One in four cases takes over 19 months.

Where does the time go? The end of the process is where it accumulates.

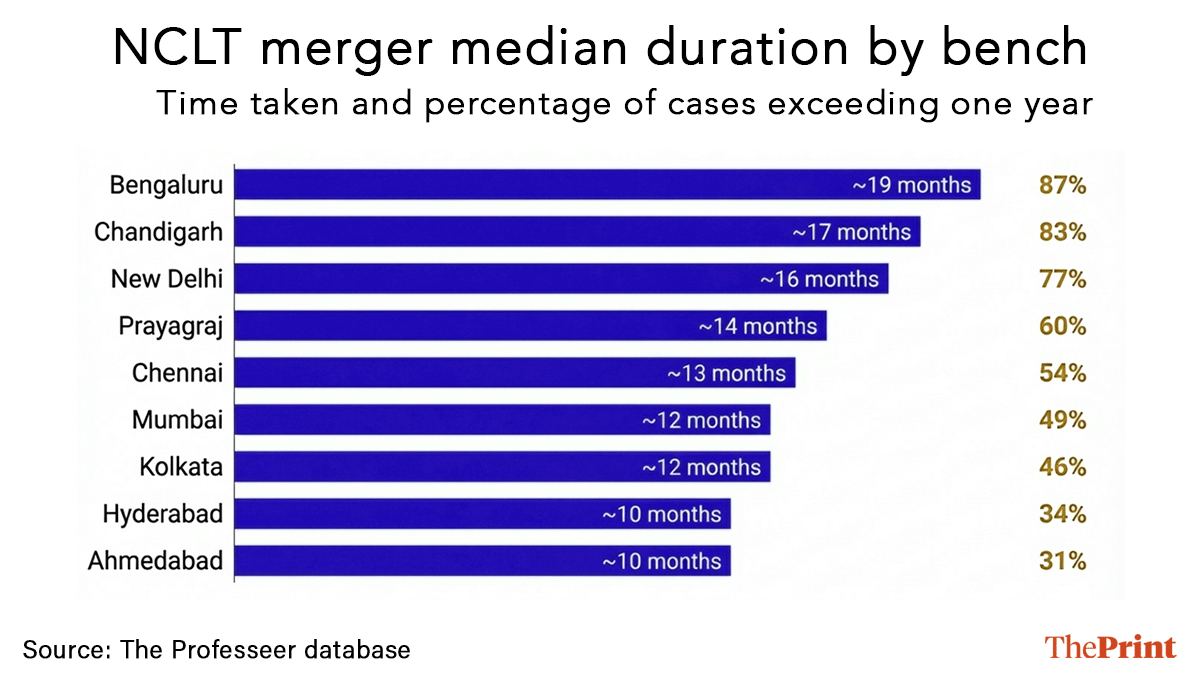

The NCLT is not monolithic. Where your case lands matters enormously. Among benches with substantial caseloads, a case in Bengaluru takes nearly 20 months, with 87 per cent of cases taking over a year. Ahmedabad and Hyderabad, by contrast, clock a median of 10 months, with only 30 per cent exceeding a year. Same law, same process, but vastly different outcomes.

Also read: Trump is dismantling the post-1991 world America built. He rejects a second superpower

It’s not about complexity of cases

The fastest route through the NCLT is avoiding shareholder meetings altogether. When all shareholders and creditors consent in advance, the tribunal can dispense with the meeting requirement. For example, if the company is a wholly owned subsidiary, the consent is a mere formality.

Nearly two out of every three disposed matters had all meetings dispensed with. In 30 per cent of cases where meetings were partially dispensed with, timelines were similar. In the 3 per cent of cases where all meetings were conducted, the time to sanction jumps by 2 months.

One might expect complex transactions to take longer. Composite schemes – bundling amalgamations with capital reductions or demergers – should logically face more scrutiny than a straightforward merger of two companies. The data doesn’t support this. Time spent in the NCLT is remarkably similar across scheme types. Simple amalgamations, composite schemes, demergers all cluster around the same median, give or take a few weeks.

This matters. If complex cases took longer, you could argue that the delays reflect genuine judicial scrutiny of harder problems. Instead, the uniformity suggests procedural friction that affects all cases roughly equally: hearing schedules, regulator response cycles, and administrative bottlenecks. The queue doesn’t discriminate.

What’s taking so long?

The law gives regulators 30 days to respond. The data suggests they often take far longer, or trigger cycles of clarification that extend well beyond that window.

In roughly one–third of cases, we identified regulators raising observations. The impact is stark: cases without recorded regulator observations took a median of 11 months. Cases with at least one regulator flagging issues? A median of 17 months – over six additional months of uncertainty.

Isolating individual regulators is difficult, since observations often overlap. But patterns emerge. The Regional Director, a civil servant appointed by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs, appears most frequently. When multiple regulators pile on, delays compound further. The observations are rarely consequential to the outcome – over 92 per cent of concluded cases are eventually sanctioned, and just 1 per cent are dismissed on merits. But each query triggers a response cycle: clarification, hearing, adjournment, repeat. The 30-day statutory window becomes a 90-day reality, or worse.

If most schemes eventually exit approved, why does the process take so long? The Supreme Court has held that tribunals must assess fairness and equity – not merely rubber-stamp applications. But when sanction rates exceed 92 per cent and dismissals are vanishingly rare, the scrutiny looks more procedural than substantive. The NCLT has become a court required to judge that rarely says no, while everyone waits.

Also read: Nepal’s political parties are back to square one. Impact of Gen Z protests fading

Will the reforms work?

The September amendments are the most significant expansion of fast-track mergers since the route’s creation. The fast-track process imposes a 60-day deemed-approval timeline, versus open-ended tribunal schedules. For group restructurings and smaller unlisted companies, this should meaningfully reduce wait times.

But are the reforms targeting the right problem?

Skipping shareholder meetings – the core mechanism the fast-track expansion enables – saves roughly two months, if at all. Avoiding regulator observations saves five. The bottleneck the government has addressed is real but modest. The regulatory back-and-forth, the stretched 30-day windows, the hearing-adjournment cycle is where the real time vanishes.

And for any case that does hit a regulatory snag, the NCLT remains the only path. Only seven Regional Directors serve the entire country, compared to 15 NCLT benches. A surge in fast-track applications may simply relocate the queue.

The question is no longer whether India can create fast tracks. It already has. The question is whether the main track – and the regulators who feed into it – can be fixed. For a country targeting a $7.3 trillion GDP by 2030, it’s an expensive one to leave unanswered.

Siddarth Raman is co-founder and CTO at The Professeer. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)