Over the last five years, India’s corporate governance regime has been repeatedly tested by a series of high-profile shareholder conflicts. These include cases such as the Tata Sons dispute involving Cyrus Mistry, the Byju’s rights-issue challenge, the BharatPe minority exit, and governance controversies at Gensol Engineering. Shareholder power struggles in these cases have brought to the forefront allegations of abuse of control, financial mismanagement, and exclusion of minority shareholders in Indian companies.

These disputes are formally channelled through the Oppression and Mismanagement (O&M) provisions of the Companies Act, 2013. The provisions empower the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) to intervene in corporate governance, halt transactions, displace boards, and force exits. How these disputes get resolved can tell us a lot about the protection of minority shareholders in India.

Using NCLT litigation data, we can evaluate how India’s oppression and mismanagement regime operates in practice.

Minority protection through O&M litigation

Corporate governance, like political democracy, is organised around majority rule, with certain fundamental decisions requiring super-majority approval. While this structure enables firms to function efficiently, it creates three persistent vulnerabilities:

- Minority shareholders can be systematically overridden.

- Decisions taken by those in control can damage the long-term interests of the company.

- Small and minority investors, who supply capital without seeking control, may be discouraged from investing altogether.

The O&M provisions under Sections 241 to 246 of the Companies Act seek to address these vulnerabilities.

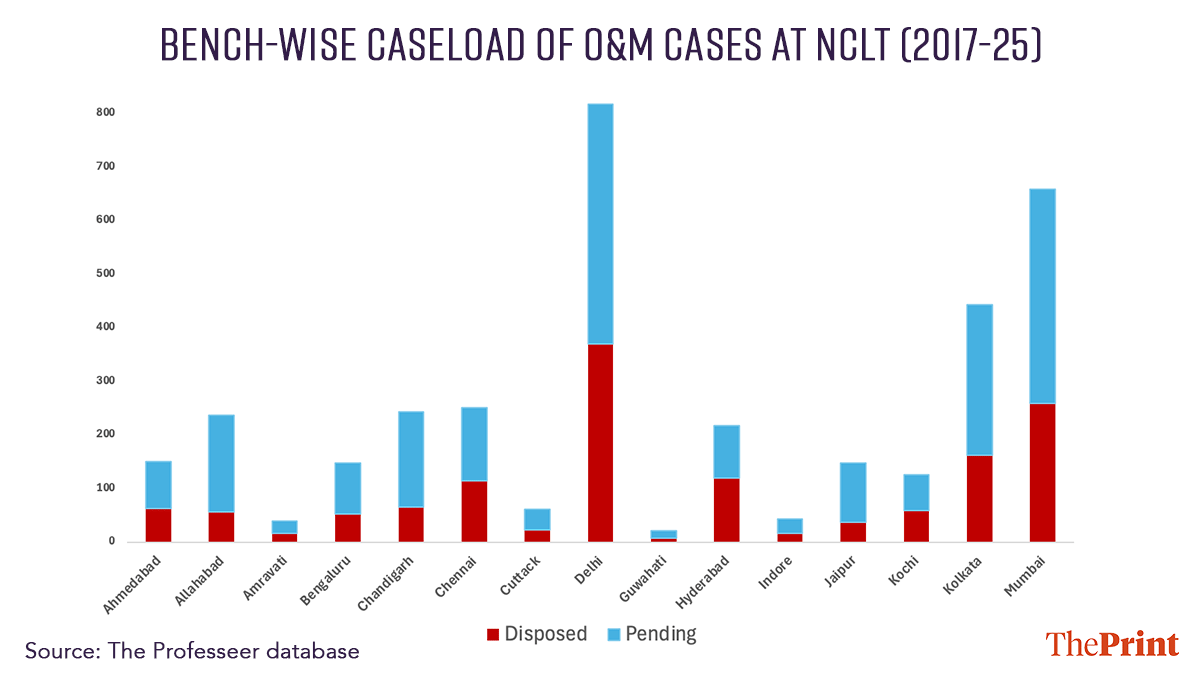

TheProfesseer’s court cases database shows that as of July 2025, about 3,608 O&M cases were being adjudicated across 15 NCLT benches. This comprises about 9 per cent of the institution’s total workload. When taken as a percentage of the workload attributable to the Companies Act (40 per cent of NCLT), O&M cases constitute roughly 23 per cent. Figure 1 below shows the bench-wise caseload of O&M cases, with the largest number of cases being handled at NCLT Delhi, followed by Mumbai and Kolkata. The caseload generated by such cases has remained fairly consistent across the last 5 years.

Figure 1

Also read: India is ready for a Davos-like conversation. Global governance needs a new host

Patterns in O&M litigation

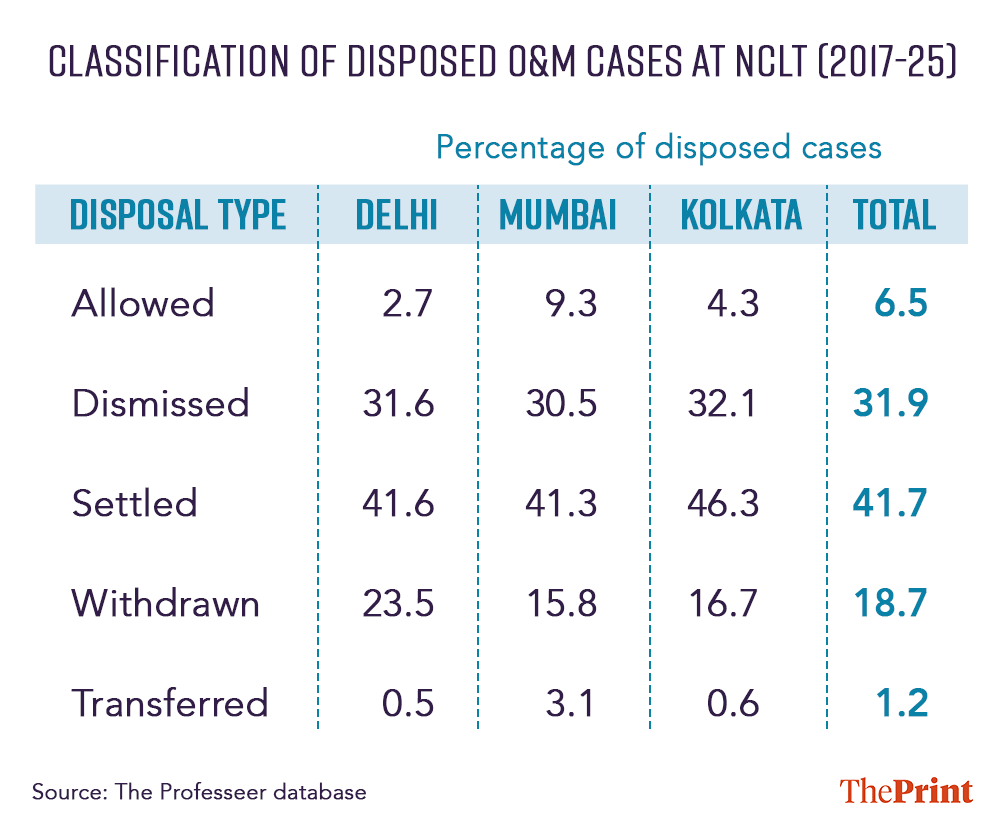

On average, 37 per cent of O&M cases across all benches have been disposed of. However, for understanding how the institutional machinery of courts give teeth to this provision of law, it is useful to examine the patterns of how such cases are ultimately disposed of.

We classified the disposed cases in our dataset according to five disposal types: Allowed, Dismissed, Settled, Withdrawn, or Transferred (Table 1). The first category, ‘Allowed’, represents cases that reached a final judicial determination after completing the adjudicatory process. Settlements and withdrawals, by contrast, indicate that parties exited the formal legal process, either because a private resolution was reached or because the costs, risks, or delays of litigation made continuation unattractive. Dismissals capture cases that were terminated without granting substantive relief. Cases are typically dismissed when they fail to meet procedural, jurisdictional, or threshold legal requirements, or when the pleadings don’t establish a prima facie case of oppression or mismanagement.

Table 1

The distribution of disposal types in Table 1 suggests how the design of the O&M regime balances the dual objectives of corporate law: protecting minority interests by strengthening their bargaining position and simultaneously curtailing opportunistic use of extraordinary remedies that could undermine the firm’s value.

First, nearly 60 per cent of O&M petitions end in settlement or withdrawal. This suggests that the act of filing itself operates as a powerful bargaining device. Once a petition is admitted, promoters face the risk of board intervention, restrictions on share transfers, and other legal, reputational, and financial consequences. These risks are sufficient to bring parties to the negotiating table, even in the absence of a final adjudication. In this sense, parties are responding not to the NCLT’s final decisions, but to the shadow of its coercive powers provided by the law.

Withdrawals could, in principle, also reflect litigation fatigue or unequal capacity to sustain prolonged proceedings. However, the pattern of high-profile cases such as BharatPe, where a petition was withdrawn following an apparent negotiated exit, suggests that withdrawal in this jurisdiction often reflects the achievement of a private settlement rather than the failure of a claim. This overlap is reinforced by the fact that withdrawals and settlements take roughly the same time to conclude—about a year.

Second, the operation of law as a bargaining tool is further evident from the fact that only 6.5 per cent of cases have gone through successful judicial intervention. This implies that the function of O&M cases as it is being played out in reality is of rebalancing power so that parties can negotiate.

Third, Table 1 also shows that O&M cases face a high dismissal rate. However, a deeper reading of these dismissal orders reveals that a majority of them (about 70 per cent) were dismissed for non-prosecution. That is, the petitioner does not pursue the case to its conclusion. This suggests a similar trend of bargains and negotiations.

Forth, the remaining dismissals exhibit necessary caution from the court in granting substantive relief. The tight statutory procedures, thresholds, and demanding judicial standards function as a filtering mechanism, ensuring that only serious cases of oppression or mismanagement proceed to intervention. While this screening role can be seen as making the process cumbersome for minority shareholders, it is economically important, given the extraordinary remedies available under O&M provisions. Screening prevents the law from being used opportunistically, and protects the going-concern value of firms from being compromised in the name of shareholder fairness.

How laws can enable negotiation

In a well-functioning legal system, most commercial disputes should be resolved through negotiation under the shadow of law rather than through adjudication. This is especially true for oppression and mismanagement disputes, which arise within an ongoing corporate relationship and concern control, exit, and access to information rather than discrete legal violations. Parties themselves possess superior information and incentives to reach efficient commercial arrangements and are better placed than courts to determine valuation, business judgement, and future control.

For such private negotiations to work, three institutional conditions must be satisfied.

- Enforcement must provide a credible threat. The O&M regime supplies this through coercive remedies such as board intervention, transaction restraints, and forced buy-outs, which make opportunistic behaviour by controlling shareholders costly.

- The law must reduce transaction costs by offsetting the steep asymmetry in bargaining power between controlling and minority shareholders. By enabling collective action and judicial intervention, company law creates a legal fiction of parity that makes negotiation feasible.

- Such negotiations require predictable jurisprudence. Supreme Court decisions in cases such as V.S. Krishnan v. Westfort Hi-Tech Hospital Ltd. have supplied stable standards of what constitutes oppression, signalling that formally lawful conduct may still be constrained by norms of probity and fair dealing. This predictability strengthens the enforcement shadow under which private bargaining takes place.

This institutional design is reflected in India’s strong performance on global minority protection indices, including a full 6/6 score on the World Bank’s Extent of Shareholder Rights Index. The experience of the O&M regime offers broader lessons for the design of commercial laws in India. An effective legal system combines strong legal remedies with credible and predictable judicial enforcement. This allows private parties to resolve disputes through negotiation, supports better-governed firms, strengthens investor confidence, and reduces the burden on courts.

Pavithra Manivannan is a Research Lead at XKDR Forum. She tweets @PavithraM_. Gokul Sunoj is an associate at The Professeer. He tweets @GokulSunoj. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)