Recently, an image of a burial of an individual with a series of shell and marble bangles on each arm from the archaeological site Ban Non-Wat in Thailand has been making rounds on various social media platforms. The burial is approximately dated to c.1000 BCE, although the context and chronology remain unclear. Despite the unavailability of references and adequate information, the tradition of wearing a series of shell bangles of different diameters is as ancient as the first urbanisation in the Indian subcontinent.

The famous bronze statuette of ‘Dancing Girl’ from Harappa and the terracotta female figurines along with hundreds of shell bangles retrieved from every Harappan sites excavate to this date, all highlight the significance of shell bangles and, most importantly, the tradition of wearing a series of shell bangles that covers the entire arm.

Thousands of years later, women of Thar – present-day Rajasthan and Sindh (beyond the borders), and of Kutch have continued this tradition, transcending 21st-century political boundaries, disputes, and time itself. How rich and extravagant is this art that could not be contained by time or boundaries? Archaeology has deciphered not just the art and tradition of adorning these bangles but has also successfully decoded the science of making them.

The beginning

The earliest evidence of shell-working comes from the archaeological site of Mehrgarh in Balochistan, present-day Pakistan. Mehrgarh is a Neolithic settlement, which marks the subcontinent’s earliest evidence of the domestication of plants and animals. At this site, a complete cultural and social evolution is noted from the 7th millennium BCE to the 3rd millennium BCE. Several structural phases, evolved cultural traits, artistic expressions, and burial practices have helped decode the period that laid the foundation for the bronze age civilisation – the Harappan Civilisation.

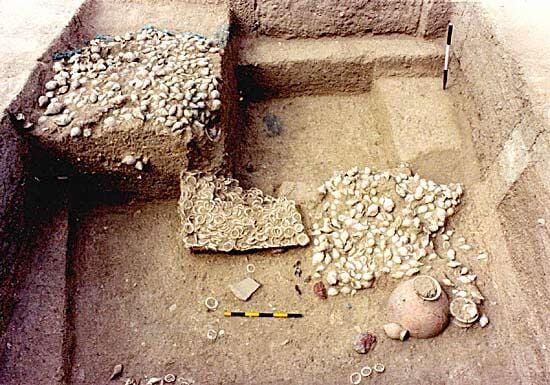

During the excavation in one of the graves from the lower level, the excavators found the deceased buried with shell bangles. This 8000-year-old evidence, when correlated with many shell bangles from various Harappan sites like Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, proved that shell objects, particularly bangles, were not only precious but are a marker of an extensive trade and production nexus involving shell-working, which was put in place as early as 8000 years ago.

How else would the inhabitants of Mehrgarh, located miles away from the coast, get shell bangles? Trade is the only means through which they may have procured the finished products. In over 100 years of Harappan Archaeology, excavations of hundreds of sites have unravelled this mystery, which starts in Gujarat.

Shell-working in Gujarat

Gujarat is known for its vibrancy, its craft, and its long-standing history of maritime trade. During the Harappan period, settlements like Dholavira and Lothal served as ports, but in reality, they were more than just port cities. At both Dholavira and Lothal, evidence of shell-working has been found as well as evidence of furnace (Lothal) and lapidary (Dholavira). However, in Gujarat, there were also settlements smaller in size than Dholavira and Lothal but dedicated solely to shell-working.

On the Gulf of Khambhat, a small village called Gola Dhoro, also known as Bagasra, was the centre of shell-working. A team of archaeologists from the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History of the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, including V.H. Sonawane, Kuldeep S. Bhan, P. Ajithprasad, and S. Pratapchandran, excavated the site from 1996 to 2005 and revealed a small fortified settlement of the Mature phase Harappan Culture, with unique evidence of shell-working and a very interesting and one-of-its-kind seal.

The excavations have revealed that the settlement may have originated as a small farming community. Afterwards, on the northern half of the site, a massive fortification wall measuring 5.20 m in width was built in three stages. This left, at any point in its history, surprisingly little space of about 50 x 50 m for the construction of residential houses and craft workshops.

The geographical location of the settlement near the Gulf of Kutch, in the regions of North Gujarat and Saurashtra, played a crucial role in shaping its economic growth. Research indicates that the inhabitants of Gola Dhoro engaged in the production of a diverse range of craft goods using materials like shell, semi-precious stones, faience, and copper. Additionally, they were involved in the collection and distribution of various raw materials, such as variegated jasper and shell, to other Harappan workshops. This strategic positioning likely facilitated trade and cultural exchanges, contributing significantly to the settlement’s economic prosperity during the Harappan period.

Nageshwar, on the southern shore of the Gulf of Kutch, is another very prominent Mature Harappan shell-working settlement. This is a single period site, meaning it thrived only during the Mature Harappan period — c.2600 to 19000 BCE — and unlike Dholavira or Bagasra, did not have any early or later deposits. Its single-period occupation also suggests its speciality, in other words, it held some importance in the broader production-distribution nexus that the Harappans had established over centuries of trade, and interestingly, the evidence also points toward the same.

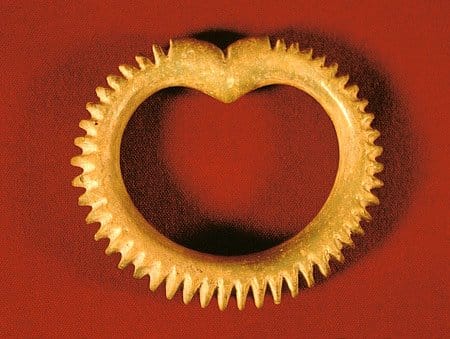

The evidence suggests that the inhabitants were producing shell objects, as indicated by the grounds stones, long concave grinding stones, mullers, hammerstones, marine gastropods Turbinella pyrum Linne, and Chicoreus ramosus Linne found at the site. Broken shell ornaments, utensils, and vast quantities of shell manufacturing waste are direct evidence of Nageshwar being a major production centre.

Moreover, the raw material to make these bangles – Turbinella pyrum – the conch shell, which is thick and sturdy, is found on the southern shore along the Gulf of Kutch. This was primarily used to make bangles, and its waste was reworked to make inlays or beads.

Similar workshops are also found at Balakot, another Harappan site located in Pakistan, where evidence of shell-working was also found. Here, archaeologist Jonnathan Mark Kenoyer conducted an experimental study, which helped in understanding the nuances of shell-working. According to Kenoyer, who has extensively worked in decoding different facets of Harappan trade, a workshop was also uncovered at Mohenjo-daro. Possibly, the raw material must have been procured from the coast and traded to craftspeople at Mohenjo-daro. What an extensive trade matrix!

Change and continuity

When scholars talk about the collapse of the Harappan Civilisation, they assume that the Harappans vanished into thin air, swallowed by the sand and soil (Danio, 2010), and with them, their great traditions and practices were also swallowed by change. But that’s not true.

Archaeologically, it was not the death of the people but of great traditions – triggered by many factors. However, there were some practices that continued. In fact, recent excavations at Vadnagar have also indicated a major shell-working workshop at the site. Whether it is the Harappan ‘Dancing Girl’ or the women of Thar and Kutch, or the person buried far off in Thailand, some traditions transcend time and borders, reminding us that change is inevitable, and so is continuity.

Disha Ahluwalia is an archaeologist and junior research fellow at the Indian Council Of Historical Research. Views are personal. She tweets @ahluwaliadisha.

(Edited by Prashant)