What’s the most important commodity for modern civilization? There’s a good argument that it’s not the ones we think about — oil, gas, copper, iron ore, gold — but something that’s ubiquitous and rarely grabs the attention of financial markets: concrete.

After water, it’s the substance we use most abundantly, with somewhere between 25 billion and 30 billion metric tons poured annually. That’s roughly three times as much as all the coal we dig up. It’s also a major contributor to the world’s carbon footprint. Cement — the crucial mineral glue that holds concrete together, made from fire-treated limestone and clay — accounts for roughly 8% of our annual emissions.

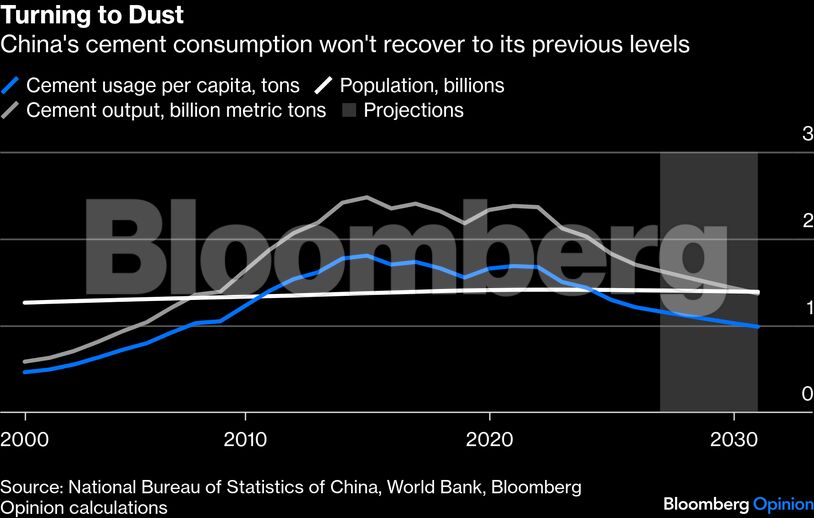

Something striking is happening right now, however. After decades of growth, cement consumption has hit a wall. On current trends, we may never return to the peak 4.4 billion metric tons that was produced in 2021, even as India, Southeast Asia and Africa continue to industrialize and urbanize. China has driven the global cement market for three decades, and still accounts for nearly half of output. But its boom is now well and truly over, with further yet to fall.

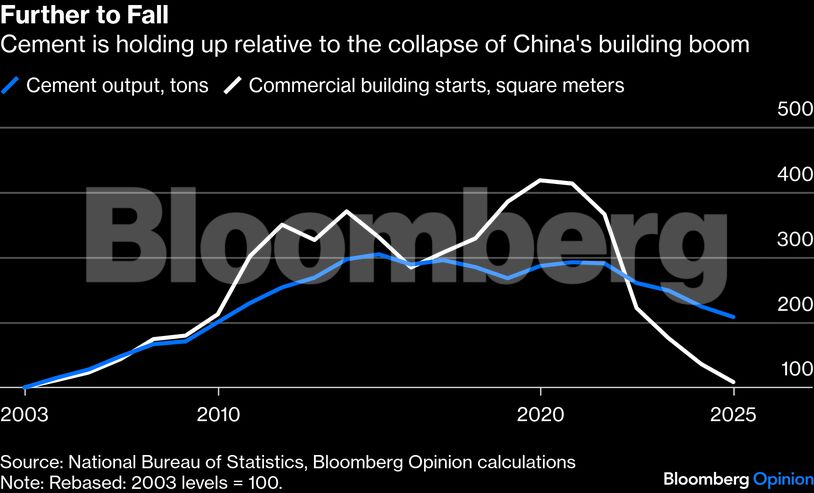

Output has already slumped almost 30% since 2020, according to data released Monday, and CSCI Pengyuan, a credit-rating company, expects it will decline for the sixth year in a row in 2026.

Prices are around their lowest levels in a decade, and factories are saddled with more than twice the capacity they need. Despite regular predictions that the market is bottoming out, the floor area of newly-started commercial buildings through December, a key leading indicator, was the lowest since 2003. Yet China is still producing nearly twice as much cement as it was back then.

If this was a one-time effect of the housing crash, it might be expected to eventually correct itself. But cement doesn’t work that way.

With most commodities — energy, for instance, or copper or plastics — consumption keeps growing as income rises, before hitting a plateau at developed-economy levels. Cement, however, drops off a cliff once a country industrializes. Per-capita cement emissions — a decent proxy for output — are about the same in the upper-income UK as they are in low-income Burkina Faso and Syria. Those in Albania and Cambodia are about three times what they are in the US.

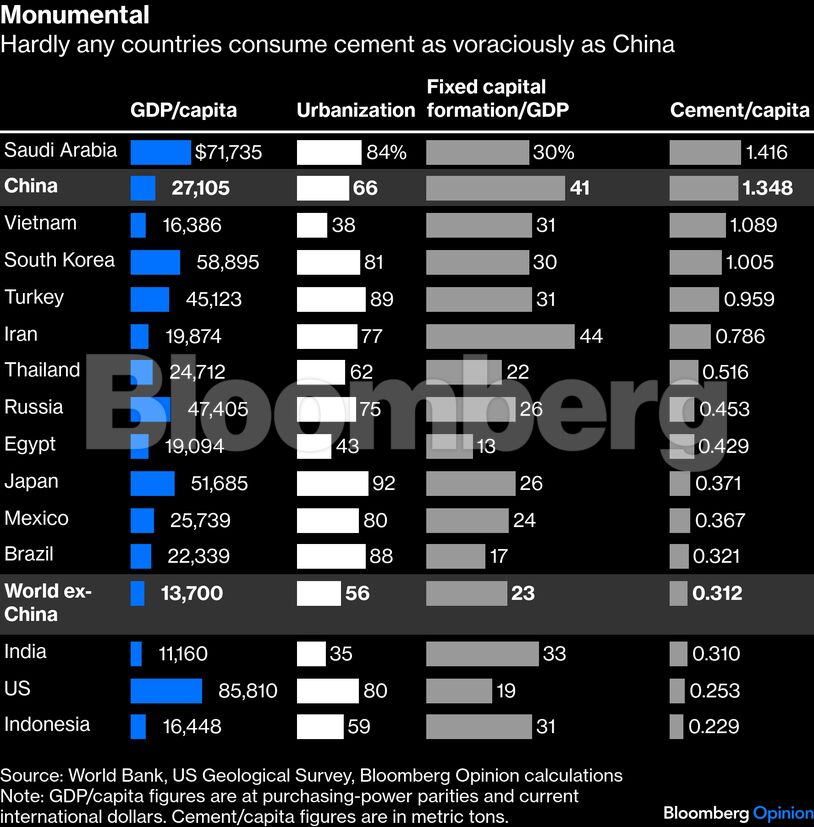

Even by those standards, China’s construction boom was extraordinarily cement-intensive. At the peak in 2014, the country was consuming about 1.8 tons per person, per year, compared to 0.25 tons in the US. At current levels it’s still sitting at about 1.2 tons, higher than any other major economy barring Saudi Arabia, and four times the global average.

Where will this number head over the coming years? It’s unlikely to fall quickly to the low levels seen in high-income countries. Infrastructure development is too important as a tool of Beijing’s economic management for that to happen. China also has more high-rise buildings and earthquake-prone regions than Europe and North America, so it’s natural that the entire economy is more cement-intensive. It’s impossible to predict how much government stimulus will distort the picture in the medium- to long-term.

Still, a relatively modest decline in such a vast market would have an immense impact. If the annual drop in per-capita consumption slows from the average 6% over the past five years to 4% between now and 2030, China would still be left at nearly three times the levels found in seismically-active Japan. Output would fall by 20%, or about 350 million tons.

No other country could come close to making up for such a monumental shortfall. Growth in the likes of Egypt, Indonesia, Turkey and Vietnam is likely to be on the order of five to 10 million tons apiece, rising to about 40 to 50 million tons from India.

This is good news, because our efforts to clean up cement’s carbon footprint have been glacial. Each ton of cement releases about 0.8 tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere — not that much when compared to metals and plastics, but huge when accounting for the sheer volume we produce. Technological fixes, by adding volcanic ash to the concrete mix, or waste materials from steel production and coal-fired power, are only likely to cut emissions by 5% to 10%.

Carbon capture and storage is a nice idea, but it’s hardly ever been seen in the wild. The countries most likely to adopt such measures, moreover, tend to be the rich ones where concrete consumption is already in decline. They’re not going to make more than a marginal difference to the big picture.

A plunge in consumption is likely to be our best bet of cleaning up this industry. Luckily, it’s coming about through ineluctable processes of economic development and industrialization. Cement’s best years are in the past. Its future is already crumbling.

Disclaimer: This report is auto generated from the Bloomberg news service. ThePrint holds no responsibility for its content.