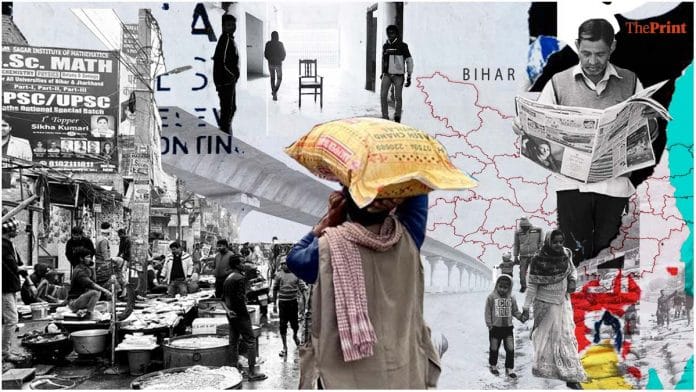

The narrative around migration and migrants is one of the core discussion points of the 2025 Bihar elections. Criticism of the ongoing migration from Bihar is a strategic slogan in the rallies, speeches and TV interviews of Opposition political parties such as the Rashtriya Janata Dal, Congress and the Prashant Kishor-led Jan Suraaj Party.

They represent Bihari migration as distressed migration and described it as a ‘palayan’ (escape, displacement etc). The media also repeats similar narratives.

Their understanding of Bihari migration is based on inputs and insights developed through the old, conventional and simplistic understanding of the life of Bihari migrants. It emerges from the theoretical optics of structuralism and neo-Marxism, which are based on the arguments of ‘developmental pessimism’ that emerged during the 1970s and 1980s. This perspective argues that migration happens due to poverty and lack of livelihood in the homeland. While this is true, it is only half the story. It’s a one-sided, negative perspective that sees migration merely as social disruption, labour loss and vulnerability of the homeland.

A newer understanding of migration emerged post the 1990s. It tied migration to livelihood, but through the lens of mobility and aspiration. BR Ambedkar also described migration as an empowering act for the Dalits and marginal communities. It breaks their pessimism, creates new hope and ruptures the oppressive social hierarchy of a society like Bihar.

I used to think simplistic academic and sallow journalist feedback to politicians may produce a political strategy that ultimately harms their politics. But I’m presenting this argument now because sometimes not understanding all the aspects of a social process and misreading the public psyche can lead to the wrong mobilisational strategy.

Parties like RJD, Congress and Jan Suraaj believe that people of Bihar are emotionally suffering due to the separation caused by migration and that migration is also causing the labour shortage and loss of human capital.

Bihar produces the largest migrant human force in the country. Over 50 percent of households in Bihar were exposed to migration. And while around 9.30 million of those migrants are seasonal, circular and long-term migrants in construction, domestic, informal, industry, mining, service, trade, and agriculture industries, a section of them also go into high salaried jobs.

As we know, migration has contradictory, complex meanings and it produces two existentially opposite impacts in the everyday life of the people in rural Bihar across caste and communities.

On the one hand, it produces pain of separation, social and household strain and distress, but on the other hand it emerges as a vital household livelihood strategy, providing economic relief to the migrants and their families. Remittances received by the migrant families are used for health-based support, and to improve the quality of life. Migration also produces social and gender empowerment.

The women who are portrayed in political electoral discourses of RJD, Congress and Jan Suraaj as the victims of migration are also empowered through it, acquiring confidence and developing economic capability. These parties can’t win by promising to slow down migration without a well-thought alternative and trustworthy plan that gives the same advantages as migration does. So, the perception of women as victims may backfire for these parties.

Also read: ‘We build India, who will build Bihar?’—Chhath train is a migrant story of despair

Dignity in migration

Bihar and Uttar Pradesh have a long tradition of migration. Naukar, Rajput and Sepoy: The Ethnohistory of the Labour Market of Hindustan-1450-1850 written by Dutch historian Dirk H. A. Kolff documents how people of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh used to prepare themselves for the military labour market in colonial and pre-colonial times.

These sepoys and other migrants used to be called ‘nukariha’. The book gives an impressive account of how these naukriha were dignified and respectable in rural Bihar. In the same way, present-day migrants who work in cities acquire dignity in their home village and neighbourhood.

Bhojpuri playwright, Bhikhari Thakur’s popular 1912 play Bidesiya portrays the suffering of a wife deserted due to her husband’s migration. That sentiment has now turned on its head. Contemporary Bhojpuri stories and songs portray prosperous migrants.

While roaming in villages in Bihar, I heard an interesting Bhojpuri song. In it, the wife complains that her migrant husband who comes from Ghaziabad on vacation is wearing good clothes and going to the local market and spending money without a care in the world. (saiyyan ghum ghum ke piy tare tadi re, saiyyan anari nikale. Jaye bazari, keene mahanga tarkari).

It reflects what I observed during my extensive fieldwork in Bihar. There is a shift in the socio-economic status of a large section of migrants and their families. They now have pucca houses, vehicles, TVs. They celebrate festivals and marriage ceremonies lavishly. All of this helps them acquire dignified status in society.

In this backdrop, if a political campaign continuously critiques migration, harping on about their supposed misery, it goes against their projected identity and hurts their feelings.

Those who study migration understand that even if migrants suffer at their workplaces, they don’t want to tell or listen to these narratives of suffering in their homeland. They want their success to be shown through stories and their lifestyle. Their families—wife and kids—who may suffer in the homeland in the absence of a husband or father want to hear good things about migrant life. They are aware of the struggle, but they perceive it as a sacrifice for a better future.

In most of my conversations with migrants and their families in rural Bihar, I didn’t find a reception of the migration narratives pushed by Congress and others. In fact, I met many migrants who came to vote who were not happy with such narratives.

So, in this socio-psychological condition, the migrant political narratives proposed by these political parties either won’t get proper reception or would be a misfire against them.

The author is a social historian and cultural anthropologist. He serves at the Vice-Chancellor of the Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. He tweets @poetbadri. Views are personal.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)

Sir your understanding is wrong. No one wants to leave there home for 10-15k jobs. There are less opportunities in bihar. No one is against migration. They are against distress migration. Offcourse people who want to migrate should migrate but it should not be for labour market. We should not be labour exporting state. It’s about job creation, quality education for all . Everyone should get the right to education. So that everyone can come out cycle. It’s about hospital. Why should be go to AIIMS delhi. Why can’t AIIMS patna can be of same standard. It’s about that. Why we need to go for education to other state. I mean to normal college not some hi fi once. So to make people rich and to break caste barriers the whole society needs to prosper in all form. It’s fight about that