De-colonisation has become the political buzzword in everything these days—from politics to the judiciary, historiography, and laws. Purging residual European influences to extract pure Indianism is the ongoing quest. But here is a counterintuitive fact.

Even India’s freedom movement wasn’t a fully unadulterated, distilled swadeshi phenomenon.

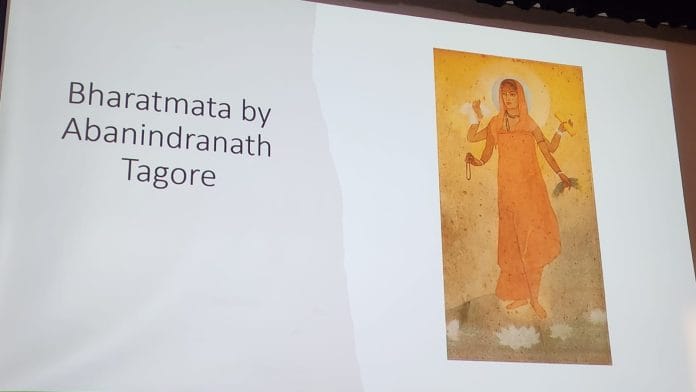

The sari-clad, four-armed Bharat Mata painting—the early 1905 image drawn by Abanindranath Tagore—had distinctively videshi influence. It had the imprint and technique of Japanese artistic style, which Tagore imbibed from Yokoyama Taikan.

Here is another interesting factoid. That same year, writer Dwijendralal Roy composed the seminal patriotic, motherland song “Dhono, Dhanye, Pushpe Bhora.” Its musical rendition by his son, Dilip Kumar Roy, had a clearly recognisable European influence.

Harvard University professor and historian Sugata Bose calls this phenomenon the ‘colourful cosmopolitanism’ and the ‘border-crossing possibilities’ of India’s nationalist freedom movement—where foreign influences could happily coexist with surging patriotism. He spoke about the art and culture that emerged during anti-colonial nationalism at the Festival of Arts at the India International Centre in New Delhi this week. The theme of the ongoing 20th edition of the festival is ‘Kalpavriksha: The Nationalist Movement – Freedom and Identity.’

“The iconic Swadeshi image of the nation as mother was not without a videshi touch,” Bose said, discussing how Abanindranath Tagore painted an arresting image of Mother Nation in the style of Yokoyama Taikan—with curving lines of the lotuses and Asiatic inspirations. “Sister Nivedita was taken by it. Initially conceived as Bongo Mata, the painting was, at her suggestion, retitled Bharat Mata.”

Also read: INDIA needs a new vision of nationalism for 2024. Invoking Nehru, Constitution not enough

Pushback and resistance

This artistic integration wasn’t without pushback at that time.

Dwijendralal Roy set the melody of Dhono, Dhanye, Pushpe Bhora in the misr kedara raag but also drew from his exposure to European music. He introduced straight notes or passages between direct notes, crescendos in the chorus lines at the end of each verse, and dramatic movements from one octave to another, Bose told a packed hall of mesmerised audience. He even played an old rendition of the song by MS Subhalakshmi and Dilip Kumar Roy from 1935 on his iPhone and sang several freedom movement songs himself, drawing loud applause.

“Conservatives were naturally aghast at the creative assimilation of tunes and rhythms of the West in his music, including his patriotic songs,” said Bose. Rabindranath Tagore defended Roy. “Some wished to banish the Dwijendralal from the domain of Indian music, Tagore wrote, because his songs have the influence of European melodies. If Dwijendralal has awakened Indian music with the touch of the European golden wand, then Saraswati will surely bless him.”

Similar European melodic features are evident in Dwijendralal Roy’s song “Bongo Amaar Janani Amaar,” which galvanised people against the British partition of Bengal in 1905. Aurobindo Ghose and Dilip Kumar Roy also rendered the Bongo Amaar song in English, titled “Oh, my India.”

Bose noted that during the era of Dwijendralal or Subrahmanya Bharati, musical evocations of regional patriotisms, whether Bengali or Tamil, were generously offered in support of the Indian nation in the making.

It was, of course, a time when articulating sub-national pride did not threaten the larger Indian imagination. There was no quest for univocal uniformity, even though unity was a pre-condition to fight against the common enemy of British colonial rulers. Such expressions didn’t fuel large-scale anxieties.

The same applied to the embrace of foreign influences in artistic and cultural expressions.

“Who wants [a] monotonous culture? Who wants a uniform culture? Who wants a colourless culture?” thundered poet-politician Sarojini Naidu at the 1947 Asian Relations Conference in New Delhi.

Also read: Hindu nationalism has taken first steps toward establishing a Jim Crow system

Patriotism and cosmopolitanism

Much of Bose’s talk mirrored the questions he tackled in his new book released earlier this year.

In Asia After Europe: Imagining a Continent in the Long Twentieth Century, Bose argues that there is a tendency to exaggerate elements of anti-Westernism in Asian thought.

He endeavours to retrieve the meanings of ‘patriotism’ from both parochialists and cosmopolitans. And he locates Rabindranath Tagore at the heart of this project.

“It is sometimes mistakenly assumed that the colonized people of Asia tended toward a cultural defensiveness and wished to erect guardrails around their imagined nations,” Bose writes in his book. On the other hand, champions of cosmopolitanism “display a visceral distaste for patriotism”.

In Tagore, the two were ‘perfectly compatible’. And yet, Tagore was a fierce critic of narrow definitions of both patriotism and cosmopolitanism.

“Neither the colourless vagueness of cosmopolitanism, nor the fierce self-idolatry of nation-worship is the goal of human history,” Tagore wrote in his 1917 book Nationalism.

Rama Lakshmi is Editor, Opinion and Ground Reports at ThePrint. She tweets @RamaNewDelhi. Views are personal.

(Edited by Prashant)

Nothing to learn from Bongs especially of the ‘intellectual’ variety who have played no mean part in fully embracing dry Western philosophies like Marxism, to the complete exclusion of their own colourful yet sophisticated indigenous social, cultural and economic traditions. Thereby converting West Bengal to Waste Bengal.

The answer to Ms. Sarojini Naidu’s question posed at the Asian Relations Conference in 1947: Islam and Muslims.