In the best of times, the World Economic Forum’s mission statement: Committed to improving the state of the world, would be an optimistic mouthful.

These, as another winter meeting concludes in Davos, are not the best of times, and definitely not for an institution which is seen as a great engine of globalisation, both by those who adore, or detest it. Globalisation is under attack around the world, not by the usual suspects, the Left and Left-leaning activists, but by the great, mostly rich and powerful populists elected in the great democracies.

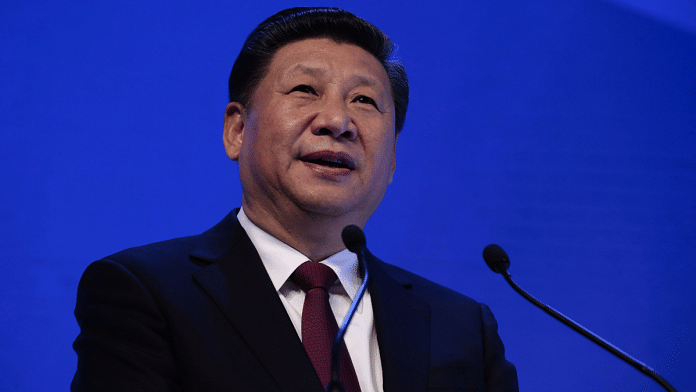

It is important, therefore, to acknowledge, that Charles Dickens’ immortal line for industrial revolution, it was the best of times, it was the worst of times, was invoked for globalisation — in fact in its most passionate support — by Chinese strongman Xi Jinping.

That the world’s most powerful Communist Party’s supreme leader is now globalisation’s most prominent advocate fully explains the state of the world today, but only if you also keep in mind that a Right-of-Republican Party multi-billionaire, elected as President of America, is its greatest critic. How do you, as a globaliser, even start imagining how to improve the state of this world?

Also read: The rise of economic nationalism is merely a response to liberalism’s failings

You begin with trying to picture it first, and Davos is comfortably located for you to run your eye across the world, west and around. From Donald Trump in Washington, to Vladimir Putin in Russia, Shinzo Abe in Japan, Mr Xi in China, Narendra Modi in India, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey and Benjamin Netanyahu in Israel, the most important countries in the world are run by all-powerful, decisive alpha males.

Each has his own unique features and style just like the countries they govern. But many common factors among them include populism, hyper-nationalism, plain, if sometimes rude, speaking. Of course, if you still find boring moments following this world, you can always turn to Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte. But for now, let’s not go there.

Mr Trump’s America, in this world, still has the most power — military, economic and technological. Mr Putin can afford to have the most fun, given his total power over Russia and warmth with Mr Trump. Mr Abe has the most problems, rooted mostly in Japan’s demography — this week, we met Kozo Yamamoto, Japanese minister with the most quaint portfolio, promotion of overcoming population decline. Mr Xi’s China has the greatest opportunity, the leading superpower spot part-vacated by an inward-looking America.

And Mr Modi’s India, let’s say, has the widest choice of options. The relationship with the US is intact and may get better, there is far too much shared interest with Russia to be offset by its improving relationship with Pakistan, Japan sees India as a favoured ally and investment destination and China, whatever its rhetoric occasionally or irritant on visa issues or Pakistan’s support at the UN, has an almost $70-billion trade surplus with India. It will become ever more important if Mr Trump lives up to his protectionist promise and creates barriers for Chinese manufactured exports.

Also read: Engaging the dragon: Xi Jinping’s China wants to be respected without being respectful

This article is being written on the day of Mr Trump’s inauguration. The natural Indian instinct would be to recalibrate its view of the world with that as the starting point, which is reasonable, but old-fashioned.

It might be smarter, instead, for India to begin with China. It is closer home, and currently making moves in our neighbourhood with the greatest geo-strategic and economic significance to India. It is now a pre-eminent power in the world in the process of resetting the manufacturing economy which gifts it most of its strategic power. It is also, for now, the most outward-looking, if not always necessarily driven by genuine commitment to common global good and definitely to altruism.

The clue for this comes from Mr Xi’s remarkable speech at Davos, positioning China as the greatest supporter of globalised economy and free trade, lecturing Mr Trump on protectionism (it is like locking yourself in a dark room which saves you from cold and rain, but also blocks light and air) and all causes that are good and virtuous today, from peaceful co-existence to climate change.

Look who’s talking you could say, for sure. Every claim China makes on free trade and respect for laws and norms of global trade is duplicitous. It blocks all global new-technology powers, Google to Twitter, creates tariff and non-tariff barriers, robs and steals IPRs, when needed raids the offices of foreign corporations and vacuums out data from your computers, conjures up new, artificial islands from the sea to expand its maritime terrorism claims, hectors neighbours, and where it suits it, happily supports a global terrorist such as Masood Azhar.

In terms of free trade as well as clean technologies and peaceful coexistence, its claims could be described most aptly in an unprintable eight-letter word beginning with ‘b’ and ending with ‘t’. It doesn’t change the fundamental reality though. Mr Xi’s speech was China’s coming out party, its claim to leadership of the world, and it is a power right next door to us, claiming large chunks of our territory.

Also read: 19th Party Congress in China: Xi Jinping is on the road to immortality

Mr Xi made a passing mention of his One Belt, One Road plan just at a time when many other world powers are retreating. Other key Chinese spokespersons elaborated on this further in other sessions, calling it a 100-year plan involving 64 nations.

It isn’t quite China unveiling a vision of its own NATO, but given its geography, something bigger. I am hesitant to call up something like a Chinese concept of an Asian co-prosperity for reasons of history but it gives us clues to that without directly using military power. The notion of CPEC, for example, has already changed Pakistan’s strategic outlook.

The manner in which China is embracing Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Myanmar and Sri Lanka amounts to a tight encirclement of India. It is in the new universe that India has to explore its strategic possibilities.

To even begin that process, we have to first reset our minds. Will a couple of more assault corps in the Himalayas deter the Chinese? Would they even want to risk several thousand boys from single-child families and a $70-billion trade surplus for the prize of Tawang? Think, and shift from tactical to strategic while there is opportunity. The world has moved a great distance from 1962 to 2017. So must our strategic outlook.

Also read: After CPEC tilted priorities, China is now happy with a second-tier role in Afghanistan